September 23, 2022

The folks who follow farmland trends learned a thing or two from this year’s midyear land values survey, conducted by the Illinois Society of Professional Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers. Namely: Variable cash leases are slowly catching on, finally surpassing both cash rent and share leases in popularity.

Of the farm managers surveyed, 31% use variable cash rent leases, 26% use cash rent leases, 26% use share leases, 12% use modified share leases and 5% are custom farming. A whopping 90% of respondents indicated they were satisfied or very satisfied with their variable cash lease.

Related: Flexing through volatility

Those surveyed say they expect a further increase in the use of variable cash leases in 2023. Why? Price uncertainty, in large part.

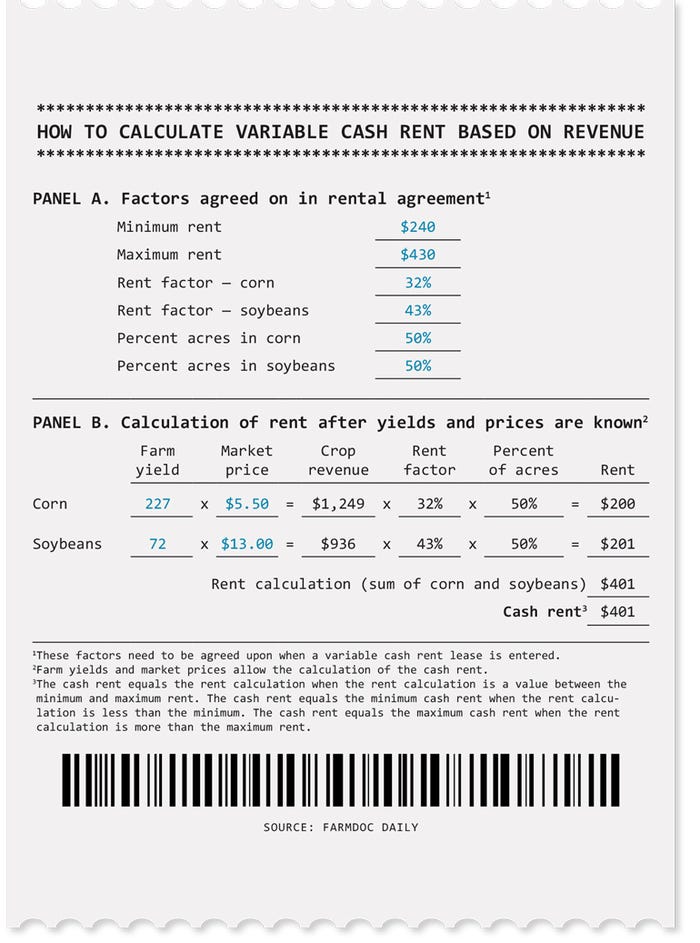

Ag economists at the University of Illinois recently released a variable cash lease analysis, and they conclude the primary advantage of variable leases is that the amount paid varies with gross revenue, reducing the hardship of setting a fixed cash rent.

“Uncertainty about future prices appears more uncertain now than in previous years,” they write.

Prairie Farmer recently asked Luke Worrell, Worrell Land Services, and Gary Schnitkey, University of Illinois ag economist, to weigh in on what they see happening with variable cash rents:

What is a variable cash rent, or flex, lease?

Worrell: A flex lease is intended to take into account what happens during a given year. Actual prices, yields and growing conditions can be factored into a final rent. It can help an owner not leave money on the table in a robust year, but also allow the farmer not to overextend themselves. With volatility the norm these days, it can be a great defense against the great “unknown” of the next crop.

Schnitkey: A variable cash rent lease determines the cash rent based on a percentage of crop revenue. As crop revenue goes up, the cash rent on the variable cash lease goes up, and when revenue comes down, rent goes down.

Are there any disadvantages?

Worrell: With so many choices and potential complexities, it can be overwhelming or confusing. It is imperative that both landlord and tenant completely understand the structure and possible outcomes.

Schnitkey: For the landowner, you don’t know what your rent is going to be for sure, and it’s going to vary with economic conditions. For the farmer, it is just a bit more difficult to manage because you do have to keep track of yield and prices, so that’s an added complexity.

Where should you start?

Worrell: Consistent and clear communication is key to nearly every ag relationship. I think exploring several different options and being honest about what concerns each party has upfront will help narrow the field down to which lease might work best.

Schnitkey: Typically, set a base cash rent, and then if crop returns times a rent factor is above that base cash rent, when you make that calculation, there’s a bonus additional payment from the farmer to the landowner. A properly structured flex lease allows those lease payments to vary with economic conditions.

Defining the terms

Ag economists on the University of Illinois Farmdoc team share the meanings of important terms involved in variable cash lease agreements:

Minimum cash rent. This protects the farmer from low revenues. To be classified as a cash lease by the Farm Service Agency, a minimum rent must be included. If a minimum is not set, the arrangement will be considered a share rent by FSA, resulting in the landowner sharing government payments.

Maximum cash rent. This provides more income opportunity for the farmer if high revenues are achieved. For more information and for a list of maximums and minimums by region, check out the Farmdoc analysis.

Rent factor. This is the percentage of crop revenue, which is generally lower for corn and higher for soybeans.

Percent acres. This number describes the percentage of corn and soybeans grown on the farm.

Farm yield. This must be calculated after harvest via delivery sheets, yield monitors or FSA county yield records.

Market price. This will be calculated using price quotes from an agreed-upon delivery point, or where the grain is most likely to be delivered. Farmdoc suggests using March to October during the current production year — fall delivery prices from March to August and cash prices for September and October.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like