It was a cold Iowa day as we began winding down the latest Farm Futures Business summit. You could feel a buzz in the air – people were pumped up, ready to get back to the farm and put some of the things they had learned in to play.

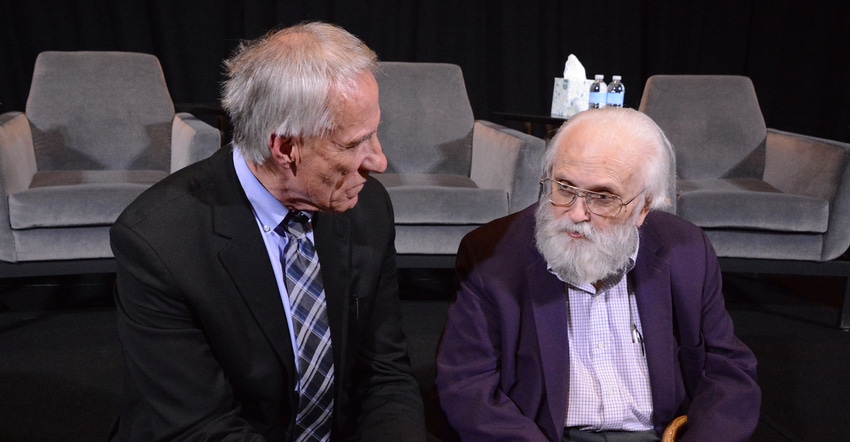

Meanwhile two drivers behind that energy sat down to reflect on nearly 100 years of teaching, not just at their respective Universities but with farm audiences worldwide. Just college professors, right? Nope. Not when the names are Kansas State ag economist Barry Flinchbaugh and Virginia Tech ag economist Dave Kohl.

No. We’re talking about rock stars - giants in the ag industry. Names known not just here, but around the world. Names known by both presidents and royalty, but mainly, grateful farmers everywhere. From ag policy to global trends and finance, Flinchbaugh and Kohl have influenced thousands of people and decisions made in agriculture.

At the summit their impact was clear, as farmers shook their hands and thanked them or asked to pose for photos. Many had been students and had used what they learned back on the farm.

Getting a chance to listen in as they reflected on their careers was a treat no journalist could resist. Here’s a few excerpts from our interview:

What’s it like to see your former students at these meetings?

Kohl: “It’s a high. And sometimes it’s not the A student, it’s the B or C or even the D student who approaches you. I never wanted to know a person’s grades coming into class. I wanted them to prove it to me. I wanted to see if we could turn a D student into an A student.

Flinchbaugh: It’s so satisfying. Part of Manhattan, KS (home of Kansas State) is called Aggieville, where the bars are. I had a student named Mike who majored in Aggieville. Today he’s probably the most influential lobbyist in ag policy. As I used to tell his mother, “Be patient, he will grow up. He has a good mind and will focus on economics.” I’m very proud of Mike because I helped him get where he is, even though many times I wanted to kick his ass.

Why is education so important in agriculture?

Flinchbaugh: I’m a product of a one-room school. My old maid aunt was my teacher for eight years. Every part of my education - from that school to Ph.D. -- I had a teacher who personally took an interest in me. If that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t be sitting here. And I’m attempting to do the same thing ever since I started teaching at K-State.

Kohl: You can’t put a dollar sign on that. It’s worth millions. I had a C student who sold his company for $98 million. You want to carry that mentorship on. It’s like throwing a pebble in a pond; that ripple goes on for eternity. We are teaching things today that will go on for generations, long after we are both gone.

Flinchbaugh: The reason my classes are always full is, the word is out the old man cares what happens to me personally. You can’t fake that; it’s either genuine or not, and students can smell it. If they have a problem, you gotta help them. Some professors are rigid and have a lot of rules. But if you roll with the punches and a student has a problem, you help them.

One thing that’s occurring today, is that it’s reciprocated. Today’s students care. We care about each other and work together, and that’s what’s missing in Washington – they don’t work together and don’t care for each other.

FF: What do you learn from the farmers you meet?

Flinchbaugh: I’ve clearly learned there’s a lot of farmers who really have their heads screwed on and know what they’re doing. The old image of the dumb farmer is pretty well gone. If they survived the ‘80s and now the teens, why, they got their act together and know what they’re doing.

Kohl: When young farmers come up and show me their cost of production or income statements, that keeps me motivated. It shows they’re actually listening. Sometimes they will challenge you and get you mad, but they get you to think critically about what you said.

Flinchbaugh: The best compliment I ever had was from a farmer in Colby, KS -- at the end of a meeting he shook his finger and said, “I don’t agree with a thing you said!” I said, “Great minds differ.” A few minutes later he said, “Next time you come to town I’ll be here.” He didn’t agree with me, but he had an open mind.

What would you do to try to fix Washington?

Flinchbaugh: I would pay their way home just six times a year, not every weekend; I want them to stay in Washington, get to know each other, play together so they’ll work together. One of (former republican U.S. Senator) Bob Dole’s best friends was (the late Democratic U.S. Senator) Ted Kennedy. Barry Goldwater was friends with President Jack Kennedy; Tip O’Neill was friendly with President Reagan. That is rare today. The human element is removed, and when you remove that, in classrooms or Congress, your ability to rise to the occasion, compromise, and collaborate, is gone.

What are your thoughts on young people? How have college ag students changed?

Kohl: Some will have problems. But there is a good group who really get it – they’re engaged, they’re inquisitive, and they have a good work ethic. They do what they say they’re going to do and follow through. They just make your day.

Flinchbaugh: They give a damn about each other. What’s happened in the last five years, A and B students are a bigger bunch, and there’s fewer C and D students. No, I’m not getting soft in my old age, they’re just more engaged, attentive, and work at it. Plus, they’re moderates politically – not extremists. That’s really important because right now we’re controlled by extremists on either end. These folks don’t think, they just drink the Kool-Aid.

Kohl: They’ve got to know how to think critically. The good students will look at both sides, and then they know how to articulate and communicate.

Flinchbaugh: Ten years ago, I would encourage students to get together in groups of four or six to study and quiz each other the night before an exam. They wouldn’t do it because they thought it brought them more competition; now, they do it and learn from each other. So they all rise instead of just a few. I think that speaks well to this generation.

If you work with young people as we do, you can’t help but be encouraged. I go home at night wound up.

What will be the keys to future farming success?

Flinchbaugh: Management is still going to be the bottom line, there’s no substitute. In the ag policy world, we’ve got programs decoupled from production and that made us more competitive; In the U.S. we got rid of the ‘price floor’ until now. These MFP payments are changing that. We’re getting too close to government again.

Kohl: Farming won’t be one-size-fits-all. There will be a group focused on commodities - big, low cost; another group focused on niche; that too will be exciting. It will be very globalized in a sense, but the U.S. won’t be the 800-pound gorilla that we have been in the past.

One of the big challenges will be disconnected consumers – they’re often not from rural areas. We’ve got to reconnect. We can do it, because 20% of the FFA chapters are in urban areas. These urban students want to understand agriculture, so I’m optimistic.

You’ve taught thousands and spoken to, well, millions. What’s the best advice you’ve offered but was not taken?

Flinchbaugh: I’ve preached for 30 years that commodity groups must work more closely together, but they won’t listen. Wheat people like to complain cotton gets all the money; or southerners look after themselves and the Midwest gets screwed, or whatever. We tried to form a wheat council that had everyone from the seed geneticists to end users like Walmart, and we finally had to give up after 10 years. People didn’t want to communicate among different commodities.

My grandmother said you don’t wash your dirty linen in public; commodity groups tend to wash their dirty linen in public and wonder why they get a bad rap instead of working together and compromising behind the scenes. Then they chew out the politicians because they don’t want to compromise.

Kohl: All the financial basics that sound easy -- people listen and nod their head, but then sometimes they don’t do it. Or the older generation thinks we don’t need to do it, or, grandpa says, ‘we never did it that way before.’

The other advice I offer but often gets ignored is, people know they should do a transition plan, but they won’t. Then there’s the senior operator who says, “I’ve got the equity so I’m calling the shots,” and the kids just roll their eyes.

Flinchbaugh: One farm family I know has three boys and a girl, all very capable in their 30s. The old man is in his 70s and won’t give up control, so the kids left. I’ve tried to reason with him, nothing works. Then he complains when his kids won’t come home and I say, “slavery ended with the civil war.”

If you want people to behave reasonably you have to give them a piece of the action and let them make some mistakes.

You’ve both done so much – what is the highlight of your career?

Kohl: It’s been a high for me to see former students go on and contribute to society. One of the highlights was being elected facilitator for the Farm Financial Standards Task Force. We had all those egos in the room and I had to get them to come together over two years to create the financial standards that we still use today. But I didn’t do it by myself, I had plenty of help along the way.

Flinchbaugh: I’ve gotten what I call old fart awards - you get so old they put plaques on the wall. But the highlight of my career was the passage of the ‘96 Farm Bill, which I worked so hard on with then-congressman Pat Roberts.

When I first went to Kansas, property taxes were a big issue, so I was hired to do policy meetings on property tax. Everybody said I wouldn’t survive, and the professors extended their sympathies. I not only survived, I consulted with the legislators, the governor, and the reforms got put in play. I joked I could live on that reputation for a decade.

The reason I survived and became a respected voice is, I didn’t tell them what to do; I discussed the alternatives with them, the consequences, and they decided what to do.

What will be your legacy?

Flinchbaugh: In the end, my legacy really is my former students and the young farmers that I helped. All I want on my headstone is, “He cared.”

Kohl: Professor Flinchbaugh, what would you put on my headstone?

Flinchbaugh: “He made a difference.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like