There are three certainties for farmers: death, taxes, and equipment trades.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s important to keep circulating equipment. Precision agriculture, GPS auto-steering, and satellite field mapping are here in a big way and understanding how to use technology to manage your operation is important when markets get rough.

On top of that, you are in a hard line of work, and your equipment shows it. Harvesting is hard on equipment. Sometimes it makes more sense to trade when “Old Reliable” isn’t keeping to her namesake.

If that’s where you’re at with an equipment deal, here are some basic accounting notes for tax basis books. The best way to think about the accounting transactions is to follow the equipment. Foregoing the research, cost benefit analysis, price negotiations - the fun parts - here is how I see an equipment trade:

You sign a loan agreement at the dealership;

They bring you the new equipment;

They take away your old equipment

Take those steps and think about what it means in accounting terms for your books:

You sign a loan agreement at the dealership = loan goes on the books

They bring you the new equipment = new equipment goes on the books

They take away your old equipment = old equipment comes off the books

Those are the three parts of the transaction you need to record in your books. We will go through a scenario, look at the transaction that you should record in your books, and then walk through what is going on from an accounting perspective.

The case of the new combine

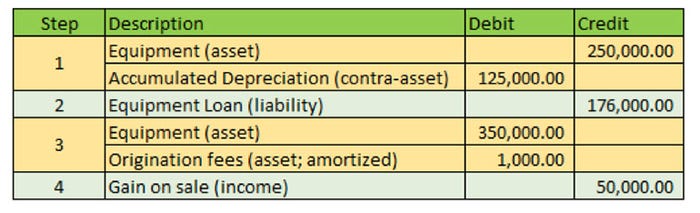

You decide that you need a new combine for the harvest season because the one purchased a few years ago for $250,000 is not cutting it anymore. Over the past few years, you have depreciated it 50% for your taxes. You talk to the dealership and they give you the damage: they will give you trade-in credit of $175,000 on your old combine if you purchase a new combine for $350,000, financed with a five-year loan. Origination fees for the loan with be $1,000, so total loan will be $176,000. Here is what the transaction will look like in your books:

Step 1: Take the old equipment off the books

My recommendation is to start with the old equipment because it will make figuring the other amounts more straight-forward. When you remove the cost for the old equipment from your balance sheet, you need to remove the accumulated depreciation with it because you want to remove your tax basis of the equipment from your books. Since you depreciated – i.e. took as an expense on your tax return (this is important to remember) - 50% of a $250,000 asset, the tax basis of that asset - to you – is $125,000. The $125,000 tax basis is shown with the $250,000 cost basis (which is a debit balance on the balance sheet) and $125,000 of accumulated depreciation (which is a credit balance on the balance sheet; known as a contra-asset) together on your balance sheet. The transaction above removes both of those from the balance sheet.

Step 2: Put the loan on the books

You add the $176,000 credit balance of the loan to your books; the $175,000 that you needed to finance after the trade-in plus the $1,000 origination fees that were included into the loan.

Step 3: Put the new equipment on the books

The value of the new equipment is $350,000 so this is the starting amount. However, since you also have $1,000 of origination fees for the loan, you need to amortize the cost over the life of the loan. In our case, this would be 5 years.

One method that I commonly see is aggregating the origination fees with the value of the equipment. The argument is that the origination fees are part of the cost to make the equipment “available-to-use,” which is a technical term that establishes when you should start taking depreciation on equipment. I would also argue that this is acceptable when it’s vendor financing as well.

Either way, that $1,000 origination should be added to the balance as an asset to be amortized with the loan or depreciated with the equipment.

Step 4: Determine the “gain on sale” for the trade

The reason that we treat the trade of old equipment as a sale is due to the new Section 1031 rules (also known as “like-kind exchanges”) that no longer allow deferred equipment gains (to clarify, that’s federal; some states still allow it).

What this means is that you treat an equipment trade as if you sold the equipment and put cash into the purchase of the new equipment. The dealership gave your $175,000 trade-in credit on a piece of equipment that you had a basis of $125,000. That $50,000 difference must be accounted for somewhere, so you have to treat it as a taxable gain. That $50,000 you are taking as income now is because you expensed $125,000 in previous tax years.

Right, wrong, or indifferent; there is tax effect when you trade equipment. If you have a year with a lot of high dollar trade-ins, work with your tax professional and try to provide them with as much information on your trade-ins as you can before the end of the tax year. Using pre-year end planning meetings is the best way to avoid any big surprises come tax time.

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like