Farmland rents usually lag a year when farm profit margins rise, and that was the case for most farms in 2021. Now, with two strong farm income years in the books, landowners are likely demanding a bigger piece of the revenue pie for 2022. Most don’t want to change tenants, but they don’t want to be taken advantage of either.

What’s “fair” is at issue. How do you proactively negotiate so that both parties are satisfied? And how do you do that with vastly different landowners, from a large insurance company to Aunt Betsy? Besides all the other hats you wear, maybe it’s time to become your farm’s customer relationship manager.

What’s important?

Communication is the first step in building a strong business relationship with each individual landlord. You can’t use a one-size-fits-all approach.

“Understand what is most important to the landowner you are working with,” says Mike Downey, a farmland expert and associate at Next Gen Ag Advocates. “Each owner is different. What pushes their buttons? Sometimes it’s more than just rent.”

Start by asking yourself these questions:

Have you gotten to know your landlords and learned their idiosyncrasies?

Do your landlords see land only as an investment? Or is it a generational source of family pride?

What values do you share with them?

Do they have a long-term goal to keep or sell land?

How will you work the next generation into the landlord relationship? Can you develop a strategy to buy or continue renting the land if it will soon move to a nonfarm heir?

Downey has worked with many farmer-tenants to develop the right lease for both parties. He recalls a recent situation where the tenant thought everything was fine simply because he paid rent on time, but the owner wasn’t happy.

“The landlord wanted conservation practices on his farm, and the farmer didn’t deliver,” Downey recalls. “This is a case of poor communication and transparency. Sometimes you just need to ask about the farm and what’s important to them. Are there things they would prefer you do differently?”

In the scenario mentioned, it might mean drastic changes in practices, which you may or may not be willing to commit to. But in most cases, landowners just want to feel like they are kept in the loop.

“Getting a fair return is sometimes not the only thing that matters to them,” Downey says. “Sometimes, it’s just making a phone call in the middle of the year, or texting them a picture at harvest. Landowners love those little things.”

One more tip regarding communications: Who should be your lead negotiator? It’s not necessarily the senior farm manager or owner. Each farm team member has strengths and weaknesses that complement each other. If your strength is marketing, but your brother or niece has the people skills, why not make them the lead? In the same vein, if a farm you rent now has a next-gen owner, would it make more sense to send one of your younger-generation managers to establish and build that tenant-owner relationship?

Lease types

Year-to-year cash rent leases are the most common in the U.S., but they have flaws. The pressure on year-to-year fixed leases is a constant source of tension between owner and tenant. When prices are down, farmers look for lower or zero increases in next year’s lease. With prices high, it’s the owners looking for an increase. No one ever really knows exactly what’s right. In a perfect world, the rent would be determined and paid after the growing season, because compensation would be based on performance. Because year-to-year cash leases lag the marketplace, it adds pressure on landlords to “make up” for not asking for an increase last year.

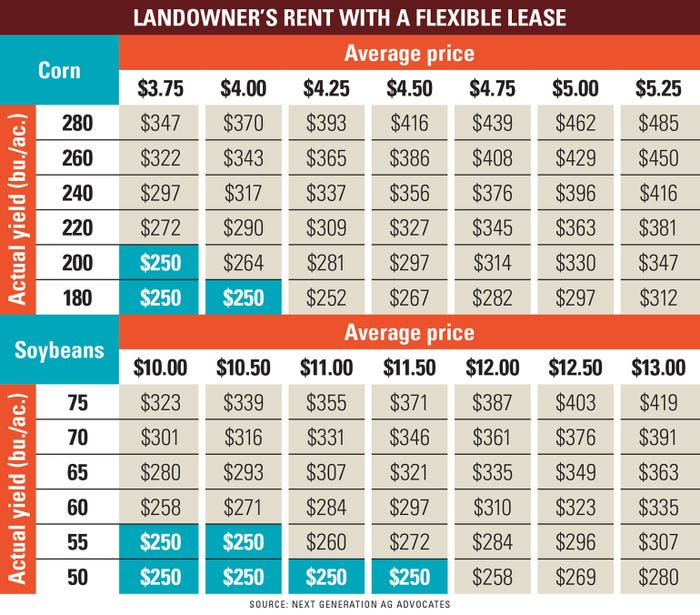

A flex lease based on an agreed set of prices and yields can be put in place to relieve that lag, Downey says. This lease sets a baseline rent — a minimum paid to the landowner regardless of the farm economy. Then it adds incremental bonus payments when prices and yields hit certain levels. Everyone shares in the upside when good times take place.

The tenant must share production information for this to work, but it relieves the yearly stress of renegotiating cash leases. And it’s a formula that can be passed on to the next generation of owner and tenant.

“The flex lease is replacing the crop share lease that was popular 20 years ago,” Downey notes. “With a flex lease, both owner and tenant feel they are in a partnership.”

Educating landowners

When prices and profits are high, farmers have the delicate task of educating landowners without coming off like they are campaigning for keeping the rent in check. But as is so often the case, landowners — particularly those not involved in agriculture — only see high prices in the headlines. They don’t read farm business publications that explain why fertilizer prices have doubled, and that seed corn is going up 10% next year. What’s worse, they may be getting information from all the wrong places.

“Be aware of the impact of local gossip,” Downey warns. “In my experience, that leads to bad results. Don’t rely on your landowner to get their information from neighbors or the coffee shop.”

One way to help landlords understand what’s happening is by sharing trusted news and analysis from outside sources. Send links to articles and personal notes on how it may impact your farming goals, not just during rent negotiation season but throughout the year. Invite them to educational meetings or webinars that discuss the challenges and risks you face.

“That takes some of the pressure off of you,” Downey says, “because there’s a lot more information out there than just higher grain prices. There are things many landowners don’t understand. There can be some extreme volatility between weather and the cost to produce.”

Learn to share

There’s been a lot of debate over the years on how much business information farmers should share with owners. But if you want to build a better relationship with landowners, you need to be transparent, whether that’s fertility, practices, yield or the technology you use. You might be surprised at the reaction.

“A lot of landowners get pretty giddy seeing color maps of their farms,” Downey says.

All of this leads to better trust in the relationship. And once you trust each other more, you can open the conversation to deeper issues, such as sharing costs of a new practice like cover crops. In the end, this will be your best negotiating tool.

“People like to work with people they trust and like,” Downey says. “Working with someone you like goes back to being open, and asking them what we can do better with their land asset.”

Bigger opportunities ahead

That trust can build empathy when it comes time to sign the next year’s lease. But trust and transparency can also open the door to bigger conversations — and opportunities for the future.

Farming is changing rapidly. Landowners may encourage — or even demand — a change in practices related to conservation and sustainability. Many cost-share programs incentivize cover crop adoption. Carbon trading platforms that require long-term commitments from owners and operators are also becoming more common.

“Better trust helps you get over the hurdle of what it costs and who should pay for it,” Downey says.

For more tips, read Mike Downey's blog, More than Dirt.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like