From their farm in western Illinois, Krista Swanson and her husband, Brett, are like a lot of young farmers their age. They’ve managed carefully, bought farmland and borrowed money to do it. But one thing she insists on?

Fixed interest rates.

“I feel pretty comfortable borrowing money if it’s against farmland,” she says. “But I’m very particular about a fixed interest rate. It costs a little more than a variable rate, but if they’re low, they can only go up. That’s a no-brainer.”

That’s where Swanson’s experience comes into play. She’s an ag economist, working as a research associate for the University of Illinois (look for her byline on Farmdoc articles), and before that, she analyzed loan portfolios for Farm Credit. From her colleagues there, she learned to be cautious with valuation and interest rate risk — hard-earned lessons many of them took from the 1980s.

“Many on the Farm Credit management team at the time had been entry-level loan officers during the 1980s, and they were all very cautious,” Swanson recalls, adding that variable interest loans made back then made any debt increase daily.

Those generational approaches still play out today, when you can mention inflation and interest rates — and debt — and likely get a different response from different generations. Before penning their recent interest rate article, the Farmdoc ag economists talked about the difference in how younger people view debt compared to those over 40.

“That over-40 generation is more anti-debt at this point, and maybe a little more nervous, where young people didn’t experience the 1980s,” Swanson explains. “Younger people tend to be more comfortable with more leverage. They became comfortable with it because of the cost of getting into commercial farming for their generation.”

And what happens if interest rates increase and debt becomes more expensive? What happens in the wake of inflation, driven by labor and government policy and global pandemics? And how’s a farmer to respond, regardless of their generation?

U.S. agriculture has entered a period of disruption and high risk, says Carl Zulauf, an ag economics professor emeritus at Ohio State University who also contributes to the Farmdoc team.

“In this era of disruption, risk will come from directions we don’t normally anticipate,” Zulauf says. “There are periods of time that the world, or a country, goes through a period where risk increases. Lots of things happen that you would normally say have a low probability, but they congregate together. We are in one of those times now.”

How we got here

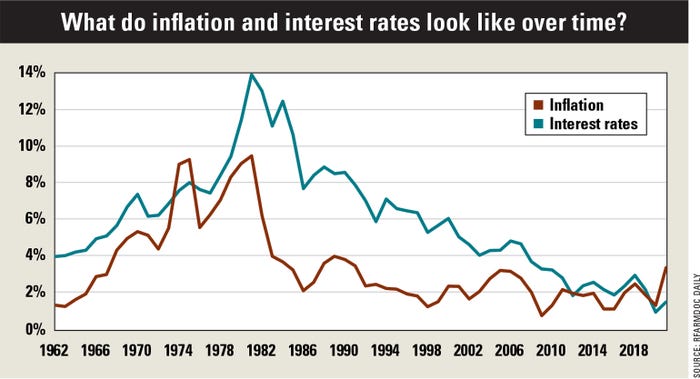

Zulauf says despite long-term run-up in federal debt, the risk is from interest flow, not the debt itself. There’s been a long-term decline in interest rates and a low period of inflation (see chart). The real 10-year U.S. Treasury Bond interest rate has been negative for the past two years, and as Zulauf points out, the only other two-year period of negative real interest rates occurred during the 1970s.

“So we have two generations that have no experience with either increasing interest rates or with inflation,” he describes, adding that higher interest rates affect farmers in three ways:

operating loans

farmland loans not on fixed interest rate

federal farm programs — the government has less money for farm programs if it’s spending more on its own interest

“If you don’t manage inflation correctly and interest rates correctly, you create longer-term problems with negative consequences,” he says.

Zulauf says inflation is related to supply chain questions, which lead to labor supply. It’s not the only factor, but it’s a big one. Economists question whether the increase in inflation is temporary or permanent; Zulauf believes the answer is in labor.

“Labor-led inflation tends to be more permanent than transitory, because you’re increasing income of workers,” he says. Labor supply is low in part because of low population growth, lack of immigration policy and retirement of the baby boomer generation. Zulauf’s point: Watch labor trends to know where inflation will go.

What it means to agriculture

If interest rates increase in response to inflation, that will affect cash flow expenses, especially for those using operating loans. And, Zulauf adds, constant higher interest rates will be a negative for farmland prices.

But farmers can take steps to prepare and respond well. Here’s a look:

Be aware of risk. That’s easy to say — and really important, in this case, Zulauf says. “We’re in a different period than we’ve been in for 40 years, and you have to change your management plan,” he adds. “That’s not going to happen overnight.”

Practice caution in loans. Swanson says lenders today generally won’t loan more than 60% of the appraised value because they’re putting a buffer in for the unforeseeable decline in land values — and that’s a change from the 1970s and ’80s. “On the lending side, a lot of the decision-makers went through that period, and they hold the reins a little tighter today,” she says. “They don’t want the 1980s to happen again, either.”

Keep labor happy. Zulauf predicts labor management will be an even bigger challenge in the next five years because it will be even more disruptive to lose a good employee. You have a few weeks to plant and a few weeks to harvest, and if you don’t have labor, it’s a huge cost. “There’s a skill set that’s unique to agriculture. You may have to pay more and may have to worry more about keeping your employees happy,” he says, adding he knows farmers who have already increased wages to keep people from leaving.

Watch per-acre profitability. Inflation makes us look at input costs, Swanson says, but it should also help boost commodity prices. Look at your farm budget and ask: What’s the negative influence on the cost side as compared to the positive influence on the price side? Inflation may not mean a fully negative impact on profitability. Watch your ratio between cost and revenue.

Review budgets now. Winter is a great time to review your financial statements from last year. Use last year’s income and expense statement, and mark it up to make a cash flow statement for this year: “Here’s what I spent in 2021; here’s how it will look in 2022.” Figure your working capital by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. Divide that by acreage to get working capital by acre. Swanson recommends FAST tools on the Farmdoc website for monthly cash flow planning, quick cash flow projections and more. You can even punch in expected cost and income and do a stress analysis: If this number goes south, what happens?

Borrow with caution. Zulauf says today’s scenario should make you leery of long-term debt that you can’t lock in the interest rates on. “This is what happened in the ’70s,” he says. “It was a seminal event in my economic education. Think about how you want to manage this if, indeed, it does change.”

Want more information on interest rates and inflation? Check out these recent Farmdoc articles:

So far, so good for farmland

If there’s a singular watermark from 1980s agriculture that farmers often point to, it’s the collapse of land values by as much as 50%. Today, despite high inflation and the potential for increased interest rates, farmland managers say they don’t expect that to happen again.

Eric Sarff, president of Murray Wise Associates and a farm kid who grew up in the 1980s, acknowledges that land markets are cyclical but says buyers are definitely still interested in farm ground, as indicated by a near 20% increase in Illinois land values in 2021.

“I think we’ll continue to see land values go up this year, but not at the crazy rate as last year,” Sarff says. Part of the reason they jumped so dramatically in ’21 was due to historically low sales volume in ’20. Pent-up demand combined with low supply, coupled with inflationary fears, caused land to shoot up — potentially artificially, as land that sold for $12,000 an acre a year ago now commands $17,000 to $19,000.

“I don’t foresee that large of a jump in the next 12 to 18 months. I think we could see maybe 5% to 7% this year,” Sarff says.

As for the cycle, he expects a small correction at some point, but the question is when.

“At some point the market will cool off, but it’s anyone’s guess as to when it’ll happen,” he says. “Historically, farmland has had dips, but overall, it has continued to go up as an asset class.”

With land values go cash rents, and Sarff says this could be a good time to negotiate 2023 leases. If you’re currently on a straight cash rent, it could be reasonable to ask for a flex lease arrangement with a 10% to 15% reduction in the base payment. Then if commodity prices remain strong, the landowner gets a bonus payment — like an extra $25 per acre if December contracts on the Board of Trade hit $7, for example.

That gives the farmer a little more breathing room on fixed costs, but both parties win if prices are high. Sarff says flex leases vary widely, and farmers can even lock in a three-year lease, which would give some longevity protection.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like