In the quest for profitable production, corn prices continue to sag dangerously close to breakeven numbers. The latest data from USDA pegs season-average prices around $3.60 per bushel.

Farmers prepare to dig their heels in for 2019, which will likely be the sixth-consecutive year of relatively low commodity prices following the drought-induced boom of 2012-13, and search for fresh ways to scrape and scratch for every possible penny to stay in the black.

What production and marketing strategies will make the most sense — and cents — this coming season?

Hedge your bets

Cody Heller, CEO of Central Wisconsin Ag Services who also farms 3,500 acres of row crops, says of his 100 or so clients, only about four of them hedge, despite the potential upside of doing so.

“We bleed equity, and we’re borderline breakeven at $3.30 or $3.40 cash in corn,” Heller says. “Hedging can help keep you above breakeven, but a lot of people don’t understand it or are afraid of it. It’s a huge problem in our industry.”

In 2018 Heller used a series of calls and puts to sell his corn at an average of $4.20 per bushel. Does he wish prices would have been even higher? Absolutely. But selling corn for $3 per bushel could sink an operation; his current marketing strategy protects profits and allows him to keep rolling into the next season.

“Get a hedging plan,” he says. “I can’t emphasize that enough. Even if it ends up costing you about 10 cents per bushel, it’s worth it.”

On the production side, Heller does a careful analysis of costs versus returns, especially when it comes to older farm equipment. When repair costs start to stack up, it may be prudent to trade that equipment or even see if custom fieldwork will pencil out.

“We don’t always look at those things very well,” he says. “Even if equipment isn’t costing you principal, it still might be costing a lot of money for repairs.”

One piece of equipment that often gives an excellent return on investment is a used grain dryer, which can be found “dirt-cheap” these days, Heller notes. Even smaller operations could reap some big benefits by investing $3,500 to $5,000 to dry grain on the farm.

“When it costs a few cents per point for someone else to dry down your corn, you can pay for a dryer for very few bushels,” he says.

‘N exposure’

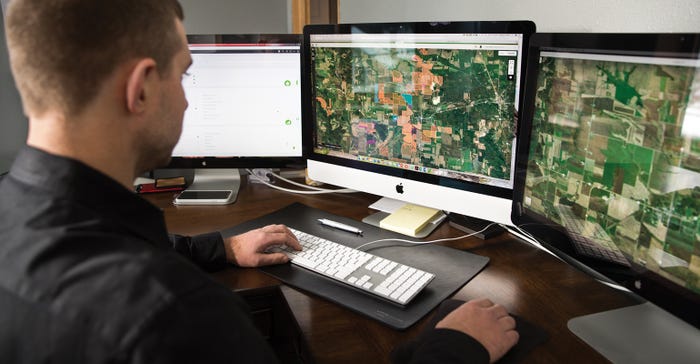

Because fertilizer costs are often the No. 1 expense in corn, Heller homes in on ways to minimize what he calls his “N exposure.” In recent years, he has turned to satellite imagery at a cost of $3 to $4 per acre. The investment more than pays for itself, as Heller is able to more effectively time his variable-rate fertilizer applications and reduce his overall rates. He calls it a win-win-win — better for his crops, his soils and his pocketbook.

Heller also sees more farmers turning to e-commerce solutions to save on input purchases.

“There’s some money to be saved by knowing what everybody else is paying for seed and inputs by using those online platforms,” he says. “It’s another way to help pad your margins and give you more of a buffer.”

Master the basics

Plenty of whiz-bang digital tools can potentially build revenue on your operation. At the same time, don’t stray from focusing on the fundamentals, says Van Larson, a crop consultant in southeastern Minnesota. A lot of great ideas are still severely underutilized, he argues.

Soil sampling is one such example. Larson says less than half of all fields get sampled on a regular basis. But this practice removes the guesswork and pins down realistic yield expectations, which in turn helps farmers better manage those fields and more accurately manage their operation.

“There are a lot of fertility and pH problems that still aren’t getting addressed right now,” he says.

Don’t cut fertilizer rates unless it’s a part of a targeted variable-rate strategy, Larson adds.

“I’m concerned about some of the fertilizer expenses we’ve been cutting,” he says. “We’re just not buying enough groceries for these crops. It can be difficult to build up fertility, but you have to at least feed the crops what they need to hit your yield goals.”

Like Heller, Larson focuses on return on investment for inputs, rather than the cost of those inputs. One example he gives is fungicide applications. He says they have more than paid for themselves in recent years, thanks to improved harvestability from better stalk quality.

ROI can sometimes cushion “sticker shock” reactions to high-cost inputs when the payoff is apparent, but farmers should avoid cutting costs that don’t actually affect the bottom line.

“Don’t try to save $1 by throwing away $5,” he says.

Weed control is another good example of ROI in action. Plenty of farmers have tried to skimp on costs for this input but end up letting problems fester and erode yield potential in the long run.

“Weed control doesn’t reduce costs, but farmers intent on doing a one-pass program are introducing a lot of unneeded risk,” he says. “You have to keep weeds under control — it’s just good management. There are plenty of good examples that a two-pass system is the way to go.”

Risk tolerance has shifted over the past five years, especially regarding hybrid selection. That’s not a bad thing, Larson says. Farmers can benefit from planting most of their acres to trusted hybrids and setting aside a small percentage to investigating new options.

“You don’t need a home run, but you can’t afford to strike out,” he says.

And if the prospect of $3.50 corn in 2019 feels like a bad case of déjà vu, buckle up — it will take a major shift in supply or demand fundamentals to significantly move the needle in your favor.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like