Editor’s Note: In our column, Then and Now, we look at farm technologies, strategies, equipment, livestock, crops and treatments from our back issues of Nebraska Farmer, and discuss how things have changed and how they have stayed the same.

In March 1941, the world was changing rapidly. World War II was raging in Europe, but the bombing at Pearl Harbor that plunged America into the war wouldn’t happen until Dec. 7. The cover of the March 8, 1941, Nebraska Farmer magazine shows photos of new equipment, including a Gleaner-Baldwin combine pulled by a Ford tractor, a John Deere disk harrow and a Minneapolis-Moline tractor with a front-mount cultivator.

Machinery wasn’t the only thing changing. A new crop technology called hybrid seed was gaining steam with farmers. One article, titled “Hybrid gives best yield,” talks about studies conducted by the University of Nebraska comparing yields of visually selected open-pollinated corn against hybrid seed.

Yield trials

The first paragraph states that hybrids — both experimental and commercial — averaged 26% superior yield to OP varieties in seven eastern Nebraska tests. Average rainfed yields for hybrid seed in eastern Nebraska ranged from 27.6 bushels per acre in Boone County, all the way up to 45.7 bushels in Douglas County.

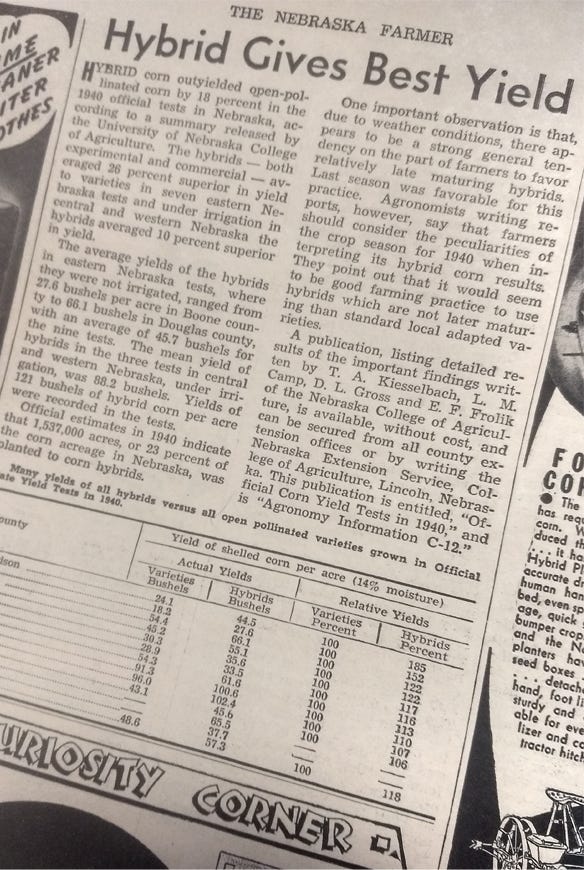

The mean yield of hybrids in three tests in central and western parts of the state, under irrigation, was 88.2 bushels, but yields of 121 bushels per acre were recorded. An accompanying table shows the comparison in 12 counties (see photo below).

Hybrid seed wasn’t brand-new in 1941, but it still was in its infancy. Two of Nebraska’s early corn breeders were H. Chris Hoegemeyer of Hooper and his son Leonard, who started breeding their own inbred lines. They founded Hoegemeyer Hybrids in 1937, when the science was still new in the state.

Leonard attended the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and learned about the potential of hybrids, along with hybridization techniques. He brought two parent hybrids home for his father to grow their first hybrid. Leonard’s son, Tom, earned his doctorate degree from Iowa State University and joined the company in 1974.

We asked Tom to give us a history lesson on the evolution of hybrids in Nebraska.

Insights from an expert

“Average U.S. corn yields were almost unchanged between 1867, when USDA started keeping records, to 1940,” Hoegemeyer says. “The OP varieties hadn’t improved much. During the 1930s, good farmers had success planting hybrids on some of the most productive land in Iowa and Illinois, but the adoption of hybrids was slower in areas with lower yield potential, like the Western Corn Belt.

"However, during 1934 and 1936, with hot, dry weather, some hybrids showed more toughness than the OPs. Hybrid seed was seen by the U.S. government as a technology to help lift rural areas and the country out of the Depression.”

Hoegemeyer says that land grant universities began investing heavily in breeding corn, as well as other crops. “When World War II started, starch was needed to produce bombs and artillery shells, and corn became a strategic commodity,” he says. “We also needed to feed the U.S. population and the troops, with fewer working on the farm.”

YIELD STUDIES: In this 1941 clipping from Nebraska Farmer, the superior corn yields of hybrid seed experienced in 12 counties across Nebraska, under both dryland and irrigated conditions, are explained through the results of a 1940 University of Nebraska study.

Higher yields and drought tolerance weren’t the only reasons for adoption of hybrids.

“They also were much less variable in plant and ear height, and stood up dramatically better,” Hoegemeyer says. “Not only were they less work to harvest by hand, but they also enabled corn pickers to operate much more efficiently.”

Double cross hybrids improved substantially between 1940 and 1960, thanks to continued investment by state universities, USDA and private seed companies.

“Both practical and theoretical research showed that the improvement available by using single-cross hybrids would be more than twice as great as among double crosses,” Hoegemeyer notes, “and the industry switched rapidly.”

After World War II, nitrogen synthesis plants were in surplus, and relatively cheap nitrogen fertilizers became available. “It was quickly discovered that some single crosses were much more responsive to nitrogen than others, and U.S. yields began growing rapidly,” he says, “leading us to our present, when USDA and university research is focused on basic science and long-term issues, while private-sector companies focus on genetic improvement.”

With trait technology advancements in the seed corn industry today, the seed that farmers plant is more advanced, with greater yield potential than ever. Yet, it is important to recognize how the development of hybrid seed began decades ago when Leonard Hoegemeyer brought home his first two parent hybrids for his father to grow, causing a tsunami movement for farmers as they shifted away from the old OP varieties to the new hybrid seed.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like