A report from the Federal Reserve titled Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy doesn’t sound like it would make much news. Financial markets had already widely anticipated release of the document, put out by the central bank at the end of August.

But traders, bankers and economists all took note of the update from the Fed, and farmers should too. It could impact everything from the interest rates on farm loans, to the value of the dollar and even farmland and perhaps commodity prices too.

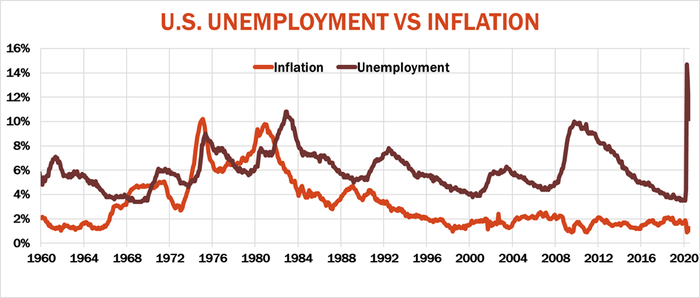

Another period of economic turmoil, the 1970s era of high inflation and unemployment, led Congress to give the Fed three mandates: stable prices, maximum employment, and moderate long-term interest rates. The bank uses interest rates as its key tool for the first two objectives. It raises rates to tamp down inflation. (Google Paul Volcker if you don’t remember paying 21% on a loan.). And it lowers rates to stimulate the economy in times of distress.

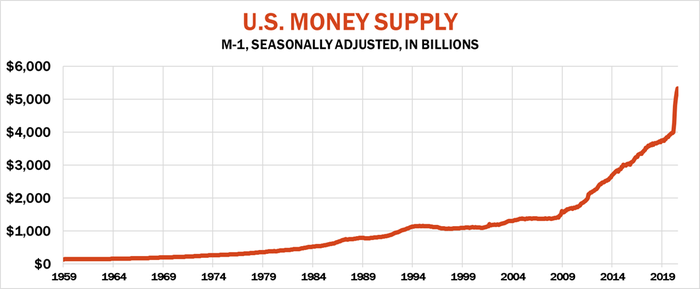

The updated policy was in the works long before pandemic forced the Fed into a full-court press to keep the economy from becoming another victim of COVID-19. It slashed its key short-term interest rate near zero and flooded financial markets with cash to keep them functioning. One measure of the country’s money supply increased by more than $1.3 trillion as of July.

The dramatic rise in the Fed’s balance sheet, along with a surge in the federal deficit estimated at $3.3 trillion by the Congressional Budget Office, may have kept the ship of state from sinking. But a big increase in deficits and the money supply was blamed for kicking off the inflationary spiral of the 1970s and early 1980s. Some wonder if the latest bath in red ink could eventually do the same.

Economists have long disagreed about what the unemployment rate should be in a full-employment economy. So, there’s no official target for that policy goal. But the central bank’s first police statement in 2012 set 2% as a target. When inflation showed signs of breeching that measure in 2017 as the unemployment rate fell below 5%, the Fed increased the pace of its tightening, raising its benchmark short-term rate to nearly 2.5% last year.

Inflation cooperated by returning below 2% even as the unemployment rate continued to drop, falling to just 3.5%, its lowest level in more than 50 years. Having both low unemployment and low inflation flew in the face of economic orthodoxy. Low unemployment was supposed to increase inflation because workers would be able to demand higher wages.

That’s where the Fed’s new policy comes in. Rather than a fixed inflation target of 2%, the new statement says that number is just an average. “… following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

In other words, the Fed suggested it would be willing to tolerate higher inflation to “promote maximum employment in the face of significant economic disturbances.”

This doesn’t mean the central bank will let inflation get out of control.. But it does indicate low interest rates aren’t away any time soon.

That’s good news for farmers, who have seen their total debt increase by 55% over the past decade. Low rates also help support farmland prices, which stayed mostly steady in 2020 despite rising farm bankruptcies.

The inflationary spiral of the 1970s and 1980s included a commodity boom led by crude oil that spilled over into agriculture. Talk of inflation right now is just that. Funds are shunning crude oil, though they helped push gold above $2,000 an ounce and have begun to get more bullish on agricultural commodities as well.

Low rates for longer could also bring a turning point in the dollar. After surging on safe-haven buying in the wake of the pandemic, the greenback lost some of its luster. Lower interest rates tend to weaken a currency, and inflation can also make investors take flight.

But don’t expect dramatic moves in most markets on inflation fears any time soon. The dust from the chaos caused by the pandemic likely will take time, perhaps a long time, to settle.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like