Duane Noland doesn’t want to build a pyramid to cement his central Illinois farm’s legacy. But he’s followed Pharaoh’s playbook to smooth out the highs and lows that agriculture has faced since biblical times.

After all, it was Joseph who pretty much invented grain storage, building up inventories in seven good years to survive famine in the seven that followed.

Noland doesn’t have that much bin space, but he says his family’s operation used profits from the boom times to drive down production costs in the lean years that followed.

Like Joseph, Noland and son Grant built storage, enough to hold a year’s production on the farm’s 5,500 acres of corn and soybeans, and installed a grain drying system to avoid high costs at elevators. They also invested in on-farm fuel and fertilizer storage, and weather-proofed fields by adding tile to improve drainage.

“We think we were able to take more control of our destiny and reduce a lot of input costs this way,” Noland says.

Like many growers today, Noland has seen it all — from the farm crisis of the 1980s when he started farming to the boom years when Grant joined the operation in 2009. Duane’s brother Dennis and son Blake are also part of the management team.

Illinois farmer Duane Noland says his family’s operation focused on using windfalls from boom years to invest in projects that would save money in the long run – like on-farm fertilizer storage.

The current run of low net farm income was a reminder about the need to make the good times last.

How can you design a business plan for a boom-and-bust industry? Here’s how to farm like Pharaoh with a game plan focusing on financial planning, long-term sales and risk management.

1. in boom years, focus on the big picture

During boom times, farmers don’t always “see” where they are in the current economic cycle. As a result, they don’t always sock away enough profit from good times to buffer the hangover years that follow.

In good times and bad, “it’s important to think about the global economic cycle,” says Vikram Mansharamani,Harvard lecturer, global equity investor and author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst.

When you connect the dots, the decisions you make may be very different from a local outlook.

“It’s not easy to look at the bigger picture in which your decisions are being made,” he notes. “Even though something makes sense from a local level, it may be a bad decision on the macro level. So it’s important to think about what is happening globally, to be more conservative when others are aggressive, and vice versa. If you’re mindful of that dynamic, it could be useful from a managerial perspective.”

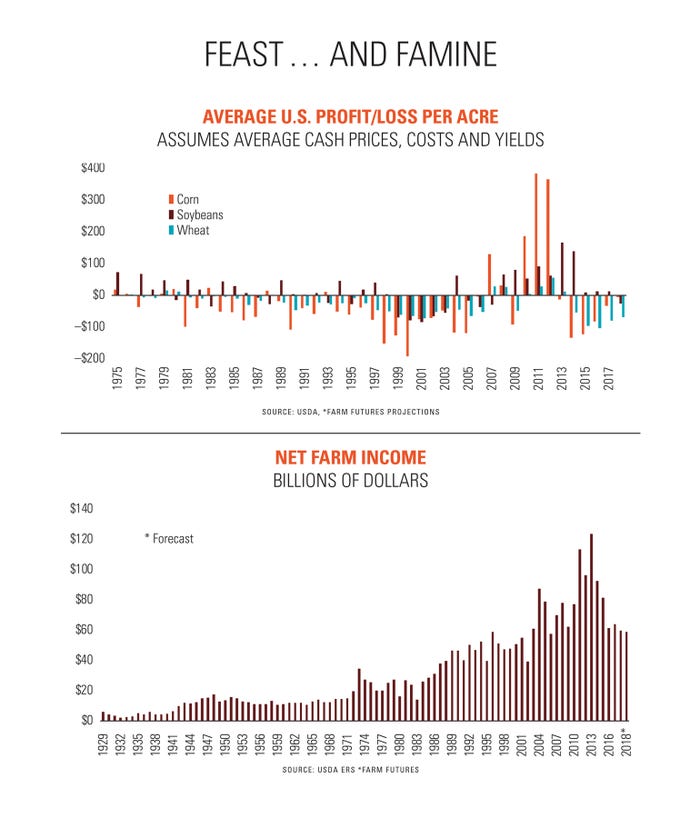

Take the current cycle. From 2011 to 2013, U.S. farmers experienced profits well above long-term averages, thanks to tight supplies and strong demand. People got caught up in the euphoria of “feeding the world.” But few industries get slapped as hard by the invisible hand of the market as agriculture.

When prices go up, more seed goes in the ground. Everywhere. The “factory” gets larger and produces more things. In ag’s recent boom, world farmers added well over 120 million acres of corn, soybeans and wheat. That fueled a 9% increase in world row crop acres from 2008 to 2014.

The take-home message? During boom years, watch world production figures. Pay more attention to global supply-and-demand conditions, not just what’s happening in your backyard. Dial in to world economic growth trends, along with weather forecasts in key ag-producing countries.

And above all, don’t expect good times to last forever, because they never do.

“U.S. farmers can be too U.S.- focused,” says Purdue economist Mike Boehlje. “They see the U.S. and start telling themselves, ‘We’re not making any more farmland.’ But in fact, in the last decade, world acreage expansion under cultivation happened in other countries, and even in the U.S. Some did come from [Conservation Reserve Program] lands going back into production.”

Even as more acres were sewn, world corn yields increased — 1.3% per year from 1990 to 2016. Since 1990, 56% of the increase in world corn production has been achieved through higher yields, and the remaining 44% has come from increased corn acres.

“There’s a technological revolution happening worldwide in every sector, in which productivity is enhanced, providing greater output for the same inputs,” Mansharamani says, “and agriculture is not immune to this revolution.”

2. Build a cushion to survive the bust years

So how do you have the financial resiliency and discipline — economists might say the absorptive capacity — to make it through downturns?

First, build a cushion of short-term financial reserves. Called working capital, this is the difference between current assets and current liabilities on your balance sheet.

You can’t hold seven years of grain on farm as a cushion (although we’ve known a few farmers who have tried.)

Purdue economists say to shoot for a 30% working capital buffer (working capital divided by gross farm income). The more risk you face, the higher that number should be. Keep monitoring your financial performance.

Lenders historically haven’t asked for that high a percentage when underwriting loans, but in an environment where you’re burning up working capital, why take the risk?

“You don’t want to find yourself, a year or two from now, having burned up whatever working capital you have and not be eligible to borrow operating funds for the upcoming year,” Boehlje says.

There’s another good reason to build a war chest for the downtimes. It not only allows you to handle bust years, but also gives you the agility to capture opportunities — likely from others who have failed around you.

“Some of the better times to grow your business are during a downturn if you’re well-positioned to take advantage of opportunities,” Boehlje says.

Should all your working capital be liquid? Paul Neiffer, CPA at CliftonLarsonAllen, suggests keeping your 30% working capital cushion in cash. If you need to avoid FDIC deposit limits, use different accounts in separate banks. Additional working capital can be put to work in less liquid investments, depending on your risk tolerance. “You can’t afford to lose that 30% cushion,” he says. “That’s going to help you sleep at night.”

3. Don’t eat your seed

Joseph made sure not all the crop was used for food: Some was held back for seed. Likewise, making it through a downturn requires making sure you don’t burn through working capital too fast. That may require changes to your cost structure.

One way to boost cash flow is to restructure loans. Growers are wary of debt, and like to pay it off as quickly as possible. But that can drain reserves. Extending terms on land loans to 15, 20 or even 30 years lowers payments in the here and now.

“It takes some of the current cash flow repayment pressures off the farm operation,” Boehlje says. “It’s a different type of financial reserve. It buys time for the farmer to work his cost structure down and convert operations from red- to black-ink profit margins and therefore have income to service that debt.

“Sometimes we say refinancing doesn’t solve the problem, but it buys you time to be able to move the operation from losing to making money, and get the income you need to service debt.”

Farmers whose land base is primarily cash rent typically have a harder time building and keeping financial reserves, because most of their equity is in their machinery line. They can’t extend land loans, or use the ground as collateral.

Historical trends tracked by Farm Futures bear out the risk cash-rent farmers face. According to Farm Future’s grower surveys, over the past decade cash-rent-only growers faced three times the variability in income as those who owned 100% of the land they farm.

“With cash renters, most equity shows up in the value of machinery, and most lenders won’t refinance based on machinery equity, as machinery values have shown a lot more downside than land values,” Boehlje says. “Cash renters are coming under cash flow pressures more quickly, and their lender doesn’t have much flexibility to help them out.”

4. Pay pharaoh

Joseph’s deal gave a fifth of the crop to Pharaoh. Egyptian farmers probably didn’t like paying taxes any more than you do. But buying machinery and other depreciable assets just to lower taxable cash income can be a trap during the lean years.

“Remember that working capital you’ve paid taxes on is yours,” Neiffer says. “Working capital you have not paid taxes on is either Uncle Sam’s or the bank’s.”

Adds Boehlje: “Spending money to lower taxes does not help you build a war chest for later on.”

Noland made sure money saved from boom years helped save money in the long run for his Illinois farm. New on-farm storage for fertilizer lets them buy products when they’re cheap.

“There were years, depending on marketing opportunities, where we’ve saved up to $100 a ton on fertilizer as a result of on-farm storage,” he says. “You take your opportunities when you can.”

“Don’t get me wrong — you have to replace equipment,” Noland says. “We have modern equipment, including variable-rate and a high-speed planter. But buying a lot of equipment wasn’t the main focus for us.”

5. Hedge for the future

There is one way to make a bull market last. During years of extreme prices, contracts for deferred delivery typically rally, too, though not by nearly as much as nearbys.

When the corn market peaked in August 2012, December 2012 hit $8.2975. Deferred contracts sold for far less. But farmers who weren’t fixated on an era of $8 corn could have hedged 2013 corn at $6.495, 2014 at $5.8275 and 2015 at $5.77.

On the summer rally a year later, 2016 corn hit $5.105. All those contracts went off the board at $4.205 or less.

Selling multiple crop years fell out of favor during the long upturn in prices from 2006 to 2012. Some who tried locked in prices that didn’t keep up with soaring production costs, as land prices, rents and inputs exploded.

Still, more than half the growers we surveyed at the end of 2017 said they’d sold crops two or more years in advance of harvest, and 1 of 4 had priced some 2018 corn. The 5% who already started on 2019 were more than twice as likely as average to be a high-profit operation.

Selling far in advance takes not only foresight, but also a good banker, one willing to finance margin calls if futures contracts are used.

Those who sell to elevators must be agile at working deals to avoid high service charges on hedge-to-arrive contracts or weak basis. And it’s essential to factor in potential for rising costs or falling yields to upside your profit projections.

Farm Future’s long-term research has shown that hedging in advance of harvest works best if it locks in at least a 15% margin over costs.

No one knows for sure when a boom will go bust, or vice versa. But by using some ancient wisdom gleaned from Joseph himself, it’s possible to build a business plan that can take some of the rough edges off farming’s cycles.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like