The latest USDA data shows farms keep getting bigger, farm numbers keep dropping, and acres of farmland keep decreasing. But that's less than the whole story.

The primary data comes from the Farms and Land in Farms 2017 Summary, released in February 2018.

Land in farms, at 910 million acres, was down 1 million acres from 2016. The biggest change for 2017 is that producers in sales class $1 million or more operated 1.3 million more acres than in 2016.

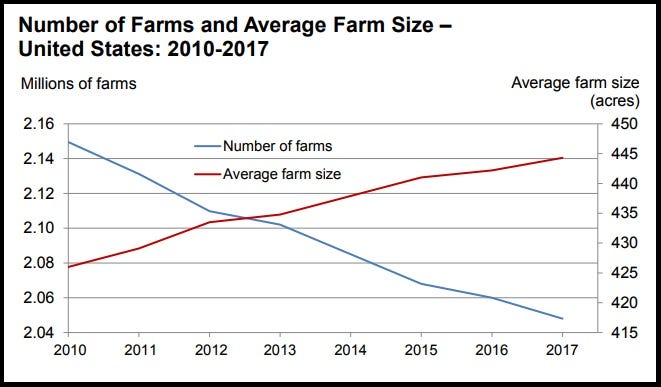

The average farm size continued to increase in 2017. The overall average size increased by two acres to 444 acres per farm. This is up from 426 acres in 2010.

These trends have been ongoing for many years. Although these data are for all agricultural enterprises defined as "farms" by USDA, the trends have been similar, yet more severe, for beef operations.

This graph shows the continued trend toward fewer and larger farms, but not anything about profits or beef operations in particular.

The most recent data currently available for beef operations was the 2012 Census of Agriculture, which compared 2012 with 2007. It showed beef cattle operations as the largest farm sector in value of sales and number of farms, with more than 600,000 farms receiving most of their income in 2012 from producing cattle and calves. But the number of these operations declined 6% between 2007 and 2012, USDA reported. It is not clear from USDA numbers whether the severe droughts from 2010 through 2012 affected these statistics. Certainly those droughts caused massive destocking in the Southern Plains, High Plains, and Southwest.

Questions not addressed in these USDA reports are efficiency and productivity by size, as well as the effect of subsidies, interest rates and tax laws.

Beginning in the 1960s researchers for universities and government entities across the world began to try and measure farm efficiencies and productivities as post-war agricultural industrialization and governmental policies that favored larger operations swept across the globe. The discussion in these papers usually focused heavily on whether large farms are the most effective way to produce food for nations which often had shrinking amounts of farmland, and sometimes on the ethical issue of whether a certain amount of small farms should be preserved.

A review of studies from the past 50 years or so generally yields assumptions along these lines about farm size:

* ERS data from 2004 showed larger farms have advantages in cost structure, although smaller farms often produce more yields on a per-acre basis. The largest farms, it said, have "small but economically significant" advantages over farms only slightly smaller.

* The smallest farms are indeed the most productive per acre, and also that security in "tenure" (ability to maintain ownership or lessee status) tends to improve productivity.

* In the case of subsistence-type agriculture, particularly in foreign countries, a World Bank study in 2013 found that previous studies which undervalued production from very small farms and overvalued large-farm production were often incorrect based on owner-operator farm-size estimates. When GPS data was combined with farmer land estimates, it found small operators tended to report their correct acreage rather than over-report it, while large operators tended to under-report their acreage. This further supported the concept smaller operations are higher producers per acre, and that larger operations are lower producers per acre.

However, it's good for beef producers to remember that size is not the most important harbinger to economic success. Back in 2006 Beef Producer reported that lowest-cost production, coupled with solid and consistent production, appears to be the key to profit in the beef industry. This was based on the Southwest Standardized Performance Analysis data kept by Stan Bevers, then an economist for Texas A&M University. Ranches in the database were in Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico.

Bevers broke those ranches into four statistical "quartiles" based on profitability, then analyzed costs and other data for each group.

A summary of those findings broke out this way:

The lowest-cost operations were the highest-profit operations. The highest-cost operations were the lowest-profit (really the highest-loss) operations. The two factors were exactly inverse.

Large size of operation didn’t specifically beget low costs or profitability.

The highest-profit operations actually posted lower pregnancy and calving rates than the other three.

Simple weaning weights were not very different across the upper three quartiles.

Only the lowest-cost, highest-profit quartile was making a reasonable return on assets at about 8%.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like