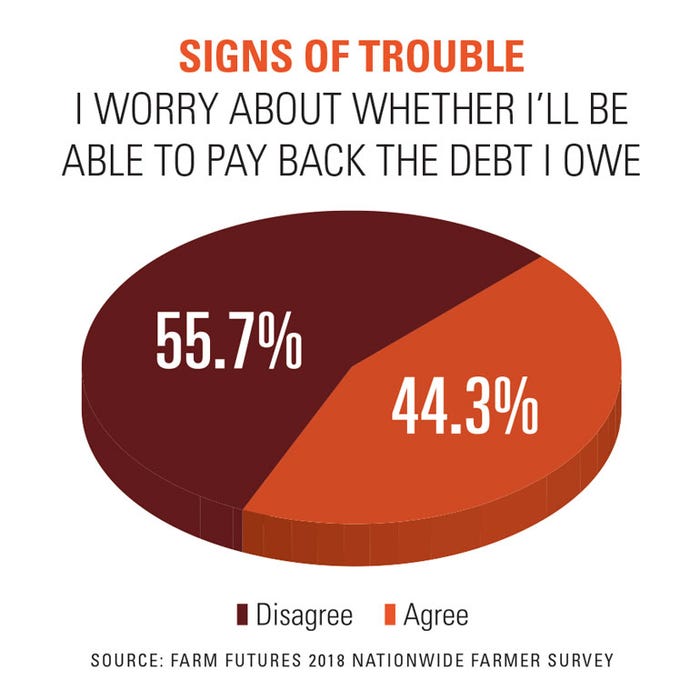

Like most entrepreneurial business owners, farmers don’t always realize they’re losing money until it’s too late. Even in a flood, sandbags can only hold off the water so long before the levees break. In Farm Futures’ most recent survey, 44% of farmers say they worry about being able to pay back the debt they owe.

Even though Farm Futures’ readers are worried, our surveys revealed less than 6% are considered financially vulnerable (based on high debt and negative income survey results). Yet the farm economy continues to chip away at working capital. If you have red ink, consider these tips to keep your head above water:

Focus on what you can control. Nick Stokes, Conterra Ag Capital managing director, says now is as good of a time as there has been in the last 30 years for producers to take a close look at their operations and where they can make adjustments to compete in tough financial times.

“We understand the financial pressure on farmers will likely continue,” Stokes says. “And factors like ongoing global trade tensions are adding to the anxiety. It’s important in a time like today, when confidence wavers, to focus on the things we can control and manage directly.”

One way is to restructure farm debt to free up working capital. Restructuring farm debt — and acreage — is one way you can take control during uncertain times.

“Though it’s not always the easiest conversation to have to start the process, it is a way to ensure that family farms remain viable in the long term,” Stokes adds.

Watch interest rates. The Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank reports as farm loan volume increased in the fourth quarter, interest rates also increased. In fourth-quarter 2018, 40% of all non-real estate farm loans were charged an interest rate over 6%. At that time in 2017, a quarter of all loans were charged less than 4%. Moreover, in fourth-quarter 2015, nearly half of all loans carried a rate less than 4%, while only a fraction had a rate more than 6%.

Nathan Kauffman, vice president and Omaha branch executive, and Ty Kreitman, assistant economist, both at the KC Federal Reserve, say the combination of increased lending needs and higher interest rates has continued to chip away at the farmer’s bottom line. For a midsized Midwest farm operation with steady financing needs in recent years, higher interest expenses increased costs about $3 an acre. But for operations requiring a moderate amount (10% per year) of extra financing, higher interest rates added about $10 an acre to annual costs.

The Fed’s recent survey found interest rate hikes are already affecting farmers: 42% say it’s forcing them to borrow more, and 33% say it’s limiting growth.

The good news for now is that interest rates look to level out in 2019. Dan Kowalski, vice president of CoBank’s Knowledge Exchange Division, says CoBank’s baseline points to the Fed standing pat on rates through the year, with a less than 25% chance that it raises rates one time in the first half of the year.

Be laser-focused on accounting. “Farmers who have laser-focus on financial record keeping are doing better than those who don’t,” says Adam Ballinger, a bankruptcy lawyer at Ballan Spahr in Minneapolis.

This abrupt fall of net farm income was preceded by a period when many were flush with cash and went on buying sprees. Bringing in an outside professional can bring a balanced look at where you’ve been, and where you need to go. “If you’re facing problems and you can’t figure it out, it’s much harder to convince lenders why they should believe in you,” he says.

Take caution with alternative forms of financing. Some lenders may deny operating loans to farmers in 2019, forcing farmers to look to alternative sources of credit, which often bring higher rates and more aggressive lending relationships. This varies from state to state, but farmers are allowed to work directly with fertilizer, seed and chemical suppliers to finance inputs. But beware: Many banks limit you from providing liens or security to others.

“By going out and getting these liens, [you may be] in breach with your original lending bank,” Ballinger says.

Whether that lien gets paid back highly depends on the growing season’s success, creating high risk for the farmer with the lien, as well as for those offering finances. If farmers aren’t being straight up with their banker, it can be a problem, and “dominoes can start falling,” he says.

Ballinger has seen explosive litigation when a bank tries to collect collateral and a farmer gets sued by everyone at once. Lenders don’t like surprises.

Better to talk bankruptcy early than too late. If farmers can’t get funding in the spring, there’s still time to commence certain bankruptcy actions to allow people to get credit, he says.

The best time to bring a lawyer into the equation on loan repayment issues is before your first default — when you can sense the problem or are close to defaulting on loan documents, he says. “Don’t lie to yourself.”

Problems become more difficult to solve if you’ve signed over, for example, your fourth amended forbearance agreement. “All that does is take leverage away from your attorney,” he says.

If you see a default on the horizon that may mean asking the bank for a resolution or forbearance agreement, it’s time to start thinking about taking the first steps of bankruptcy. If you move forward on the resolution or forbearance without looking at alternatives, you could be giving up a lot of your rights in bankruptcy.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like