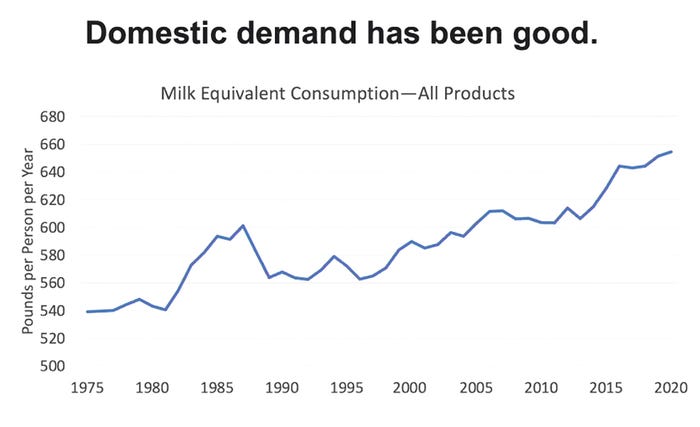

U.S. consumer demand for milk and dairy products peaked back in the 1940s and declined quite a bit through the 1950s and 1960s, according to Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “But since the 1970s, we’ve been clawing our way back up.”

Domestic demand has been good, Stephenson noted during a Professional Dairy Producers Dairy Signal webinar held March 22. Per capita consumption of all dairy products is at an all-time high, he said.

“Even in 2020 and 2021, we had increases in consumption of all dairy products,” he noted. “What we were consuming was a little bit different because we were spending time at home. Cheese consumption was flat the past two years. It didn’t grow, which is unusual because cheese consumption in the U.S. has been growing since 1975.

“In 1975, we were consuming 14 pounds of cheese per person, and last year we consumed 28 pounds per person. So, cheese has been the real driver of the dairy industry for quite a few years.”

Stephenson said there has been growth in other categories, too. “Yogurt has been a growing category. We had a big growth spurt when Greek yogurt came on the scene in the mid-2000s,” he said. “That has slowed down a bit. It grew during COVID when we had more meals at home.” Butter has also grown a lot since the mid-2000s.

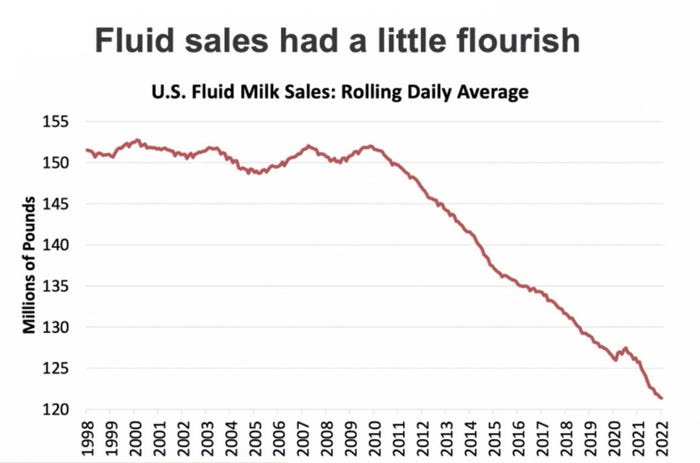

“Fluid milk consumption had a little flourish during the pandemic in what otherwise has been a sad tale,” Stephenson said. Since 2010, fluid milk has dropped from 150 million pounds per year to 120 million pounds today.

“During the pandemic, we picked up an extra gallon of milk at the store to drink with meals at the table, or we used it in cooking,” Stephenson said. “But since we’ve been eating out again, we’re back to our sales decline for fluid milk.”

Stephenson said when he was growing up in the 1960s, like most kids he had cold cereal with milk for breakfast.

“Now I eat yogurt for breakfast almost every morning,” he said. “We’re still consuming a lot of milk, but we’re making some different product choices.”

Stephenson noted that as recent as February, 82% of all meals in the U.S. were still being eaten at home.

Milk supply

Stephenson recalled there was good news about milk prices in January 2020, and then COVID-19 hit in March and there was too much milk.

“Then we had the [Farmers to Families] Food Box Program, and there wasn’t enough milk, so we began to increase the dairy herd, and in 2021, we had the most dairy cows we’ve had in almost 40 years,” he said.

Cow numbers in the U.S. grew from 9.3 million in March 2020 to 9.5 million in May 2021. Today, cow numbers have retreated to 9.35 million due to skyrocketing feed costs, Stephenson said. Milk per cow also rose during the past two years.

“Our markets are actually tight right now,” he said. “Milk production is less now than it was last year. Normally, we are used to being up 1% to 2% in production year over year, but now we are down in negative territory. We’re drowning down inventories of dairy products, and that’s what is giving us strength in price and the optimism we have for the year ahead.”

Stephenson said 2022 will be a great year as far as milk prices paid to dairy farmers.

“We’re looking at milk prices $6 above what they were last year,” he said. “But the cost of feed, fertilizer, fuel, labor and everything else will be up, too.”

He said export demand is greater than ever, and the U.S. had record dairy exports in 2021, exporting 17.5% of all dairy products produced.

“Domestic demand is fairly stable and is very predictable,” Stephenson explained. “Exports are volatile. But we are dependent on exports. We’ve increased dairy exports across the board. We have a lot of products that are quite exciting for the rest of the world, and they have been demanding these products.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like