As the assistant crop manager for El-Vi Farms in Newark, N.Y., Matt Wunder was already using Corteva’s Granular Insights and Business programs to more effectively manage data to plan, grow and analyze each field. So, when the company approached him about enrolling in its carbon program, he gave it some thought.

“We enrolled in the carbon program in February and are really ramping up our cover crop program this year,” says Wunder, who adds that the multifamily-run, 3,400-acre farm will go from about 40 acres to about 600 acres of cover crops this year.

“And because we are in our fourth year of using Corteva’s Granular Insights farm management system and already keeping in-depth records, this just involved another layer of logging practices into the carbon program. It was a good fit,” he says.

The demand for cutting greenhouse gases is growing, putting more push behind the need to sequester carbon in the soil with cover crops and reduced tillage.

Corporations face increasing pressure from investors, employees and customers to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. To offset their pollution, these companies purchase carbon credits. The Corteva Carbon Initiative first launched as a pilot program in April 2021 to corn and soybean farmers in Illinois, Indiana and Iowa, followed by an expansion in August.

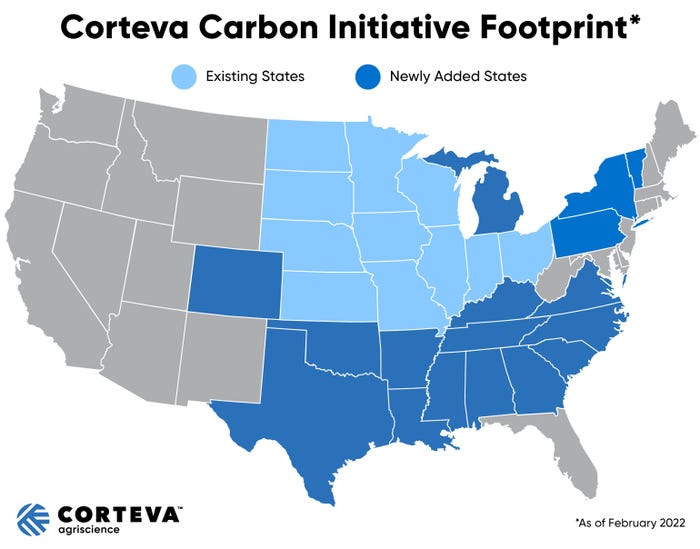

CARBON EXPANSION: Corteva recently announced another expansion to its carbon initiative, adding 17 new states and two new crops.

The company recently announced another expansion to 17 new states and two new crops — sugarbeets and peanuts. This expansion increases the initiative's footprint to a total of 28 states and 19 crop types.

Newly approved states include Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia.

Choose practices

At El-Vi Farms, they milk about 2,000 cows on two sites, 5.5 miles apart between Rochester and Syracuse. Crops are primarily a corn and alfalfa rotation with a little bit of wheat and some winter cereals.

The carbon program has many components, with farmers getting paid for practices they choose to implement.

“We planted about 250 acres of winter triticale, which counts as a cover crop. It doesn’t matter whether you terminate it with herbicides in the spring or harvest it,” Wunder says. “Because we are a dairy, where the program doesn’t fit for us is with tillage because most of the acres have manure applied. To get the benefit of the manure, you really have to incorporate it into the soil.”

The Corteva program includes a strategic collaboration with Indigo Ag, whose ongoing investments in science and technology have continued to expand eligibility and improve the process of generating rigorous, registry-issued carbon credits at scale for farmers, says Emma Fuller, lead for the Carbon and Ecosystems Services Portfolio at Corteva.

Farmers remain in control of their practices and can use Corteva’s free digital tool, Granular Insights, to securely log their practices, measure their impact and generate premium credits. Indigo sells credits generated each year directly to buyers through its buyer network. Grower payment is based on the average price of total credits sold that year.

Corteva and Indigo ensure growers always receive 75% of this average price with the security of a guaranteed minimum payment of $20 for each generated credit. For those who enroll in the 2022 crop year, farmers could expect to receive up to $30 per credit from increased market demand, Fuller says.

“People get the biggest return when they can implement cover crops and no-till,” Wunder says. “We know we aren't going to get rich off it. So, for right now, we would be happy if the carbon program just covered the cost of establishing the cover crops.

“These practices are good for soil health, so it's something farmers should be doing regardless,” Wunder says. “But if you can get paid a little bit, it makes it all the more worthwhile. For some, it might be enough to justify switching from conventional till to a strip till or no-till — to help offset some of the cost of making that switch.”

In Corteva’s program, payment for credits produced in a given year vest over a 5-year period. This vesting schedule, Corteva says, encourages growers to maintain practices without a long-term contractual practice commitment — allowing flexibility to change practices based on agronomic need.

“Corteva’s carbon program is pretty flexible,” Wunder says. “They understand that, in farming, not every year is going to be conducive to getting all the cover crop acres out or established. So, if it’s a terrible, wet fall and you don't get anything accomplished other than harvest, you can pause the program for a year. You don’t get paid, but it doesn’t affect you adversely.”

“We are definitely keeping an eye on fertilizer this year,” Wunder says. In addition to cover crops and reduced tillage practices, credits can also be obtained by moving nitrogen application from the fall to the spring.

Corteva encourages growers to evaluate the carbon program to see if it would work on their farms, but Fuller advises not to chase a carbon payment unless it makes agronomic sense.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like