In recent decades, as the North American wild pig population has been on the rise the problems associated with the animals have kept pace. Hard to control, the animals have wreaked havoc in many farmers’ fields and, increasingly, in more urban areas.

At the same time, more and more hunters have found wild pigs to be an excellent reason to set the dogs loose. The surge of hunt-related adrenaline is proving difficult for advocates of a severe crackdown on the animals.

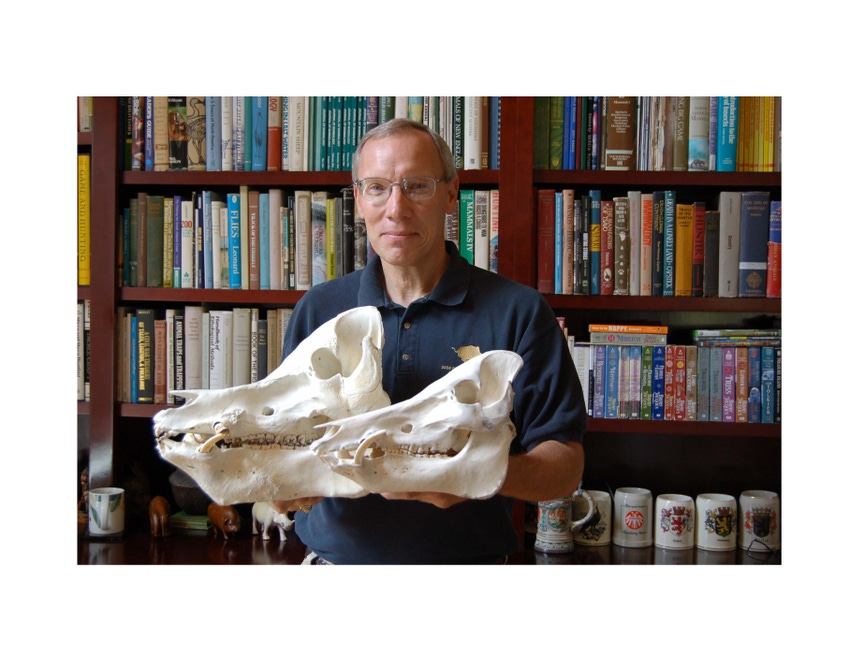

John “Jack” Mayer is the go-to man when assessing the state of wild pigs in the country. Mayer, Manager of Environmental Sciences at Savannah River National Laboratory in South Carolina, has been studying the animals for decades. Mayer spoke with Delta Farm Press in late October. Among his comments:

How did you get into wild pig research?

“It goes back a long ways. I hunt and so it started out as an interest in the pigs as game animals.

“Later, I attended college and was searching for a graduate research topic to land on. Wild pigs were a continuing interest so I just decided to pursue that. Forty-one years later and I haven’t stopped.”

So you’ve been watching as the wild pig problem exploded.

“That’s true. It’s interesting that when I began working on them back in the early 1970s into the 1980s there was a growing interest in wild pigs as legal game animals. There were states that actively stocked pigs in the wild during the 1950s through the 1970s. In the 1980s, there were states giving them legal game status.

“The problem blew up in the 1990s when a ‘pig bomb’ went off. The interest in these animals as a game species went viral. People who like hunting wild pigs didn’t want the bother of having to drive south to do it. Folks in the northern tier of states figured out they could ‘fix’ that problem. All they had to do was get a trailer-load of pigs and take them where they wanted to hunt. The pigs will certainly be happy to take care of their end.

“That was completely illegal, of course. But being illegal stopped very few who wanted to do it.

“There are also commercial fenced shooting operations in a number of states across the nation -- literally hundreds of them. Well, pigs don’t fence well and they’ve been escaping from those operations in virtually every state where these facilities exist.

“The combination of those two things has led to the rapid expansion of these animals throughout North America much faster than they could have done on their own. This is a classic example of man messing with Mother Nature and why that’s a bad idea.”

Hunting

On hunting wild pigs…

“It really is a lot of fun. That’s the challenge and conundrum with wild pigs. You have an animal that has a lot of potential as a huntable big-game resource combined with being one of the worst invasive species on the planet. There’s nothing else like it.

“People pay upwards of $1,000 per hour to go up in a helicopter and shoot wild pigs. They aren’t going to do that with fire ants or zebra mussels.”

Region of the country that has more wild pigs?

“Historically, they’ve been found more in the South and parts of the West Coast. That’s where these animals have been around the longest and so are well established.

“In parts of the South people have been hunting wild pigs since the 1500s. So, it’s an ingrained part of the culture. The same is true of the Hawaiian Islands, although they’ve been hunting them since even earlier.

“The areas that have had them the longest are where most of the animals exist and where the biggest problems are. However, even in states like Texas, Florida and Georgia, where these animals have been since early colonial times, we’ve seen a population boom.

“They used to be found in a large portion of Texas but, over the last couple of decades, they’ve expanded even more. Largely that’s because of the hand of man. Wild pigs are now found in parts of every county in Texas. We used to say, ‘Well, west Texas is too dry. They won’t make it there.’ We were wrong.”

On how quickly pigs expand their range…

“Pigs don’t expand that fast. If you watch a pig population it will expand its range an average of about four miles a year in any direction. It can be up to 30 miles but it usually isn’t that fast.

“Yet, over the last 20 years, they’ve jumped from the southern tier states all the way up into Canada. They didn’t do that without help.”

True damages

On the commonly cited estimate of wild pigs causing $1.5 billion in damages annually…

“I believe that estimate is a gross underestimate. That figure is based on every pig, on average, causes $300 per year in agricultural damages and control costs. Then that’s extrapolated out to the estimated pig population.

“However, that doesn’t include the environmental damage, the wetland damage, the depredation of native animals and plant species, vehicle collisions, property damage to fencing, or potential disease impacts.

“Consider the 2006 E. coli outbreak in Californian spinach. I believe three people died, 60-some people came down with unique type of kidney failure and several hundred others were sickened.

“That all came about due to wild pigs running around on one farm. They picked up the E. coli from cattle on a neighboring property and then came onto the farm. They were wallowing and defecating in the drainage ditches around the spinach fields. Water was then being pumped from the ditches for irrigation.

“That led to people being afraid to buy spinach so it hurt all the farmers even though it was isolated to that one farm. The spinach farms in California lost something like $75 million.

“Another example is from the 1980s with a National Guard jet that was taking off from Jacksonville International Airport. As he was speeding down the runway the pilot saw a brown blur out of the right side of the cockpit. Turned out two wild pigs were trying to beat the jet across the runway.

“The front landing gear hit the pigs. They ended up a greasy smear on the tarmac. Fortunately, the pilot had the presence of mind to eject. The plane was still on the ground, of course, so the parachute deployed just a moment before he hit the ground. The jet was destroyed -- $16 million lost due to a couple of pigs.”

On pig biology and how they turn feral…

“Pigs go wild quicker than any other species of livestock that we have. Why that is we’re not sure but it’s something that’s been recognized as far back as Charles Darwin.

“They’re amazingly adaptive. They’re the ultimate survivors being able to eat almost anything and live almost anywhere. They also reproduce very rapidly. When you turn pigs loose in an unfenced area, they’ll just take off and take care of themselves.

“A pig will go wild within a matter of weeks. As far as physical changes, it depends how old the animal is when it goes wild. If it’s already an adult animal you’ll probably only see a drop in the body weight. If it’s a younger animal, however, when it grows up it will be markedly different than a sibling in captivity. That’s because the quality of food available to the wild pig drives the physical changes. If you feed a pig a lot of Purina Pig Chow you’ll end up with an animal with a fairly large body, a fairly dished dorsal profile, and a much wider skull. Contrast that with a wild pig that’s grown up in the swamp: a smaller animal, a fairly flat dorsal profile, and a longer snout.

“A lot of the information regarding this has been misrepresented. You’ll hear, ‘When they go wild, their tusks grow, their hair gets much longer.’ Well, that all depends of the age of the animal when it went wild.”

Range expansion

On Mayer’s research…

“I’ve looked at the different types of damage these wild pigs cause. Since I work at the Savannah River National Laboratory one thing we’ve been concerned with is radionuclides. The worry is those getting into the human food chain from hunter-harvested animals.

“I’ve also looked at comparisons of harvest methods. Is there any method that better focuses on certain age and sex combinations? Is trapping better for dealing with older animals? With younger animals? Males versus females?

“But there are a lot of people out there whose focus is: how can we kill pigs better? Folks are now using military technology to reduce the number of pigs. They’ve been quite successful in some areas.

“There’s also what seems to be every type and form of trap door available, of bait combinations, of trap configuration. It’s amazing how that’s become a cottage industry in this country.”

On the wild pig expansion…

“Something we’ve seen in the last 20 years is the expansion of these pigs into developed areas – suburban and even urban. So, there have been homeowner associations that have collectively hired trappers or have put up fencing in an effort to control these animals.

“It’s the community that deals with them because the pigs will go in and rip up everyone’s yard. That’s meant a consolidation of resources to get a handle on the problem. That’s certainly happening in Texas, California and Florida.”

Can the problem ever truly be put to bed?

“You’ve got the push-pull of eager hunters combined with an invasive species. The two sides of that equation are very much separated and entrenched.

“The sport hunting crowd -- and, again, I do hunt -- are very fond of their wild pigs and don’t want to give them up. The environmental and agricultural side of the house is concerned with all the damage being done. The divide is so extreme I don’t know if it can be bridged.

“As far as options for controlling numbers of the animals there are two that show promise. One is a pig-specific toxin. Several labs are working on that and are hoping to have a license for use soon.

“Other labs are working on an oral contraceptive. That way, if you can’t kill them at least you can keep them from reproducing. They haven’t cracked that nut yet, though.”

More on wild pigs’ impact…

“Wild pigs are established in 36 states and have been reported in 47 states. Only Rhode Island, Delaware and Wyoming haven’t reported wild pigs.

“When we first began working on this, it was hard to get people to take the issue seriously. It’s taken a long time for the Chicken Little warnings -- you know, researchers saying ‘The pigs are coming! The pigs are coming!’ -- to finally kick in. People now know this is a real problem and is costing the country a lot of money.

“This is really out of hand. The federal government has even ponied up $20 million to help control the problem on a national level. The USDA is about to release an EIS (Environmental Impact Statement) on how they plant to deal with the crisis.

“Back in the late 1990s, the USDA had a plan to eradicate brucellosis and pseudorabies from the United States. The single reason they were unable to pull that off was the inability to deal with the endemic presence of those diseases in the wild pig population.

“Well, if a foreign animal disease like African swine fever or classical swine fever (hog cholera) ever gets into our wild pig population we’d be unable to control it. Then, there’s risk of wild pigs moving that disease to our livestock. The value of our livestock resources is collectively in the hundreds of billions of dollars. If that happened everyone would feel the pain in the form of food prices jumping.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like