Jim Purlee can summarize the pros and cons of farming on his own in two sentences.

“The biggest disadvantage of farming on your own is you don’t have a wealthy father or grandfather to cover your mistakes,” says Purlee, who started farming near Galesburg, IL on his own in 1978. “On the other hand the one advantage that far outweighs that risk is that you’re forced to run it like a business, because you don’t have any backup.”

Historically single proprietor operators were the backbone of U.S. agriculture. The model was pretty simple, dating back to the 1800s when settlers moved west and broke the prairie. You farmed the land, handed it off to a son, who handed it off to his son, and so forth.

Today, as farm size explodes and business complexity mounts, more farms are structured as multi-generation family corporations, neighborhood partnerships, or even multiple farm partnerships with men and women in management roles. There are plenty of advantages to these family structures - more dedicated labor, more folks with skin in the game, and a talent pool to segment special tasks like marketing or accounting.

Can the single-operator model still succeed in an age of consolidation and specialization? We set out to track trends for this group and compare performance to farms operated by multiple family members.

Who are they

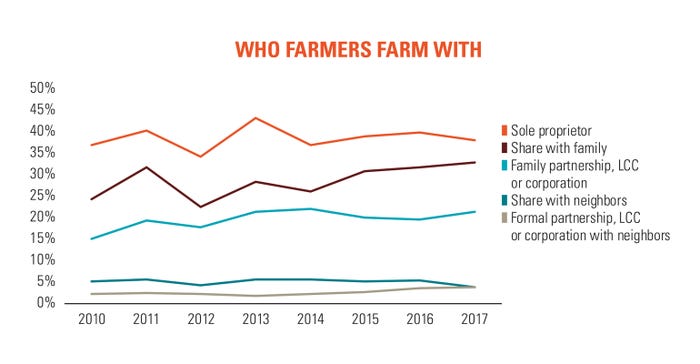

According to Farm Futures surveys, 39% of farmers are sole proprietors, not sharing labor or equipment with family members or neighbors. Just less than half either share with family or are set up as a family partnership, LLC or corporate structure. Another 5% have equipment sharing agreements with neighbors, while about 3% have a formal partnership or corporation with neighbors – so-called collaborators.

Our surveys show the number of sole proprietor farmers falling as the number of growers who work in a family partnership, LLC or corporate structure, grow.

According to Farm Futures surveys, 39% of farmers are sole proprietors.

To be sure, most people don’t choose to farm on their own, or with others – it’s a choice made for them, usually from family circumstances. Jim Purlee’s dad died when Jim was 9, so he never had a mentor. He went to college, had a couple careers, then borrowed money to buy 160 acres. A few years later he bought equipment and rented land from a retiring neighbor, and his farm career launched.

Purlee added purchased and rented land over time, and his nephew, Sam, eventually joined the team. The operation now grows 10,000 acres of no-till corn and soybean with six full-time and 12 part-time people.

He’ll be the first to tell you that he’s had plenty of help along the way. Success doesn’t happen in a vacuum, even if he was the only one signing checks.

Based on our survey data, farmers who work in share business structures seem to be under stress now because they tend to be younger and don’t have as much working capital. Those who farm with family in formal partnerships, LLCs or corporations appear to be checking more of the boxes used by better marketers.

On the other hand, those who farm by themselves still worry about debt, and they don’t have quite as high returns on equity compared to farmers who work in family structures, “because those share people are able to get stuff for free and farm more acres,” says senior market analyst Bryce Knorr, who crunched the data. “On the other hand, farmers who do it alone have less debt.”

Closer look at highly profitable farmers

We looked at the single operator category and isolated the highly profitable single operators. What did we learn?

On average they own fewer, but custom farm more acres

They analyze data

They have a business mindset

They have written marketing plans.

They have more employees

They are more aggressive about forward contracting grain sales. Over two-thirds of the highly profitable single operators told us they understand and utilize forward contracting and hedging tools to manage risk and make profits.

“I’ve always had to do my own marketing,” says Purlee, who had 100% forward contracted his 2018 crops by January and has part of 2019 crops already pre-sold at profitable levels. “Whenever prices are high enough to cover my obligations I’ll lock in prices, and I started dong that in the 70s.”

Highly profitable single operators have better management skills because, at some point, they are managing everything. As they grow the farm they can spin certain tasks off on employees or outside consultants.

“I’m good with people skills, but I’m weak in other areas, so in some cases, I hire experts,” says Purlee. “As the farm has gotten bigger I’ve needed help with bookkeeping and tax work so I have a good CPA who helps me a lot.” Purlee also works to empower his farm team, and that helps his decision-making process.

“We used to be formal about this but it really works best if you constantly accumulate information, constantly ask for feedback, and keep good notes,” he says. “The people who actually do the work here are the ones who have to be empowered to make decisions, so I really listen a lot.”

Another advantage to farming alone is the ability to learn how to make better decisions early on.

“The person who starts out farming on his own must make decisions right away,” notes Purlee. “Those decisions get easier over time. But a lot of family operations, sometimes they don’t get to make decisions until they are in their 50s. If a person doesn’t get to start until their 50s they don’t have as much experience doing it, which could be a negative for working in a family farm.”

Pluses and minuses

Bill Christ, who farms 1,600 acres near Metamora, IL while juggling an off-farm insurance career, has a similar viewpoint.

“Sometimes I wished I had a brother to farm with, but when I talk to those brothers who farm together I get the perspective that maybe it doesn’t always work as smoothly as they had hoped,” he says. “On my own, it’s easier to make a decision because I don’t have to take it to multiple family members. If it’s a bad decision it’s on me, but it doesn’t take as long to make a decision, and I don’t have anyone second guessing me.”

For a single operator – especially someone with an off-farm job - time management can get dicey at certain times of the year.

“I don’t do crop spraying anymore because it’s so timely,” he says. “I have to do all the marketing, budgeting, input research and purchasing – I don’t have anyone to fall back on for those jobs. It would be easier to have someone else to review that data with, because sometimes decisions are made without input from other people and there might have been something I missed - to at least confirm that the decision I made was the best one available.”

Team with many talents

A big advantage of the multiple family operation is the talent pool available to the business. That’s what Mike and Pam Clemens discovered as they brought their son and daughter into the 5,700-acre corn, soybeans and wheat farm near Wimbledon, ND. Daughter Rachael, an accountant, is married to Joe Ericson, who manages the farm’s technology. Their youngest son, Brad, is working into the business.

“Rachael keeps track of finances so we can sit down as a group and find out what is the best thing to be doing from pre-buying inputs, upgrading facilities or investing in equipment,” explains Mike. “She can analyze that because she’s got all the raw data. She’s our numbers gal.”

While Joe, a former pharmacy technician, has mastered farm technology, he is not as mechanically inclined as Brad, who gravitated to farm equipment at an early age.

“That’s Brad’s strong point,” says Mike. “Our employees could do these things if we needed, but having family members do it is better. They have skin in the game.”

A family operation can also pick up the slack when someone goes missing, notes Pam.

“Say someone has to go to a farm meeting,” adds Mike. “If Joe has to go, Brad will cover for him. We can cover each other much better than having an employee stepping into a role of running a high-tech piece of equipment. My 76-year-old employee is not going to step into that planter, nor would we want him to.”

Communication is key

Multi-generation family operations tend to ignore younger operators in the decision-making experience. To avoid this, the Clemens do daily debriefings. Together they create a work plan for tomorrow’s activities.

“About the third month after Joe started, we decided communication needed to improve, so we started the debriefings,” says Mike. “My dad and I farmed together for 20 years and could read each other’s minds, but with the new guys coming on board, communication was lost and we started to get frustrated. We knew it could be fixed.

“We feel we’re passing along more decision-making experience through these meetings. I test them, but I don’t set them up for failure. We try to talk about challenges that may be coming.”

Another advantage for the family business: equity.

“When the young guys look to buy equipment or land, we don’t co-sign for them, but we would step in if we needed to,” says Mike Clemens. “They are doing what we expect them to do, so it’s an unspoken rule between us, that if you get into trouble financially we would back them up. But we’ve never had to do that because of the ‘in-house training’ that has worked in our operation from generation to generation.

“One of the neat things now is that people in our community are noticing,” says Mike. “Some farmers have approached Joe and Brad about renting or buying their land because we have a track record of paying our bills, and as good stewards of their land.”

Christ says he’s often wondered if having more family members involved in his farm would have made it easier to expand.

“I’m looked at as a one-man show at times, and to rent more land, landlords are looking for bigger operations where they can be more confident things get done in a timely manner,” says the Illinois farmer. “There’s a perception that when you pull into a field with two or three combines and six semis, you’re going to get things done.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like