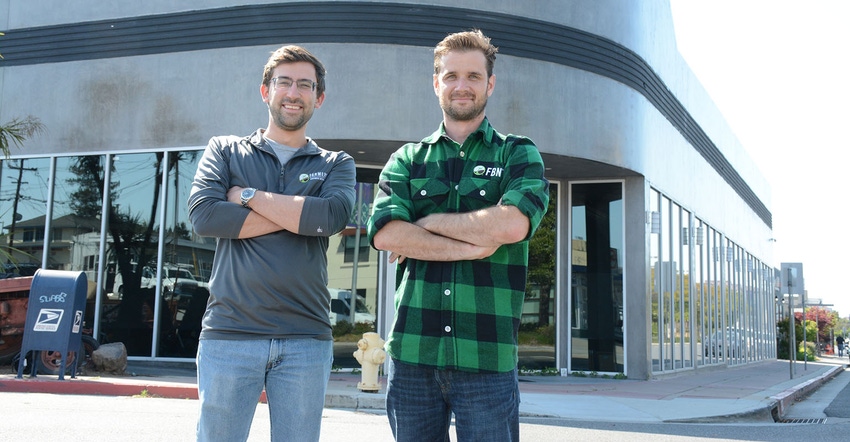

Step inside the Farmers Business Network headquarters in Silicon Valley and it’s hard to believe you’re at Ground Zero for one of agriculture’s most disruptive forces.

Inside this modest two-level building, where grease monkeys once tinkered with late-model Fords, geeks and software engineers quietly analyze data and pore over code for an increasing number of farm input and service-oriented programs.

These days this maverick startup is tinkering with agribusiness giants -- and they’re not always getting a welcome reception.

“We’ve had seed company dealers say they had to get trained on how to handle farmers who ask them about FBN information,” says Charles Baron, FBN vice president and co-founder.

In today’s environment of consolidation and tough economic realities, “farmers need options,” adds Megan Fallon, FBN head of partnerships & communication. “Anything that is truly disruptive will be hard.”

Amazon for seed?

The company’s offerings claim to give farmers a clearer picture of the complex, sometimes mystifying world of input prices for seed, chemicals and fertilizer. And those efforts have not always set well with seed companies.

“It’s not as simple as, let’s make FBN the Amazon for seed,” says Andy LaVigne, President and CEO at the American Seed Trade Association. “This year is a perfect example; You can’t downplay the service that seed companies provided farmers this spring, searching and finding seed supplies for short season hybrids when the weather shortened the growing season. That’s a service to farmers.”

FBN is in fact a member of ASTA, which includes member companies that produce seed from alfalfa to zucchini, and from conventional, biotech, and organic. The company is backed by $200 million from companies like GV (Google’s venture capital investment arm) and has yet to show a profit.

FBN’s 8,300 farmer-members in the U.S. and Canada, with a claimed average farm size of 3,600 acres, pay $700 annual fees for the company’s online stores, health insurance product, marketing services and data reports. With data from 30 million acres and growing, FBN aims to become the largest anonymous farm data-sharing network in the world.

You paid what for that hybrid?

FBN launched in 2014 with Seed Finder, a report aggregating millions of farmer-volunteered data points on seed plantings, including yield potential for individual hybrids. A farmer provides anonymous hybrid, soil, location, and yield results to FBN which aggregates the information with other growers across millions of acres; in some regions the data is more robust than in others. You can re-sort the results however you want, by soil type, state, whatever – and discover price range paid for those hybrids.

From this data came FBN’s seed ‘relabeling’ report, which in effect shows the realities of multiple seed companies selling the same genetically identical varieties under multiple brand names, often for different prices.

Leaders at several seed companies and ASTA called the ‘relabeling’ terminology misleading.

“Relabeling is how FBN has framed it, but seed companies deal with farmers every year, so farmers know what they are getting,” says LaVigne. “The seed companies are there alongside the farmer at planting and harvest, or when there are problems, like this year. It’s a very intimate relationship. We don’t believe there’s an issue there with respect to how companies label varieties in the bags.”

To be sure, several factors do impact the price of seed: company financing, early discounts, volume discounts, seed treatments, or cash discounts, to name a few. FBN data showed price discrepancy by region – so called ‘zone pricing,’ where Iowa and Illinois farmers paid higher prices for the same hybrid that farmers in other states could buy more cheaply. FBN claims these ‘seed zone prices’ were established in the 1990s as part of Monsanto’s efforts to guarantee traited seed performance; the guarantees eventually went away but the zones stayed.

“Once companies started pricing by region it was a way to optimize profitability,” says Baron. The zone pricing made it difficult for farmers to buy seed outside their zone -- conventional or genetically modified, he adds.

“I can’t comment on pricing because that’s not our area of responsibility, but companies do produce for regions whether it’s conventional or biotech, to supply whatever demand farmers have in those areas,” says LaVigne.

Both Baron and LaVigne explain that when farmers buys traited seed they are actually buying an IP licensing agreement to use intellectual property on that farm in that year only, and agree that it cannot be sold.

“What that agreement actually blocks them from is buying from a different region – so a farmer in Iowa can’t run a truck to Missouri to save $50 to $100 per acre,” says Baron. “Even online, that company can’t sell you product at a better price.”

ASTA’s LaVigne says price differences may be more influenced by the timing of your purchase.

“If a farmer goes to a company and wants to buy all the seed for their acres in November they will likely get a better deal instead of someone coming to that seed company in March,” he says. “Seed companies gamble that about 80% of their inventory will have the same demand as last year; the market for the other 20% is harder to determine based on changing conditions like we had this year. If a farmer decides to switch to conventional from biotech seed in March, his or her options may be limited.

“As for getting a better price based on geography, if you come in from out of state I’m going to question why you are there,” LaVigne says.

Across all companies, the average price of corn seed purchased by FBN farmers is about $270 a bag (GM) and $175 (conventional). FBN sells some ‘high performing’ conventional corn seed for as little as $99 a bag. The company also sells off-patent glyphosate-tolerant soybeans for a national ‘no-zone’ price of $33 a bag, and for an additional fee you can keep the seed two years. FBN does pay a trait licensing royalty but has a ‘no zone’ pricing model – it averages out the costs and everybody pays the same for a specific hybrid.

Baron maintains that farmers knew about zone pricing but had never seen a map that showed what those zones cost them. “Have people been doing business in a vacuum?” he asks. “Absolutely.”

Transparency winners, losers

FBN’s efforts to provide transparency around zone seed pricing and seed relabeling is “democratizing information in a new way,” says Jonah Kolb, Managing Member of Moore & Warner Ag Group, a farmland management and agtech consulting company in central Illinois.

He notes that agriculture has plenty of price discovery on the grain market side but very little on the input side - until now.

“Now that FBN is providing this transparency it’s understandably going to eat into the margins enjoyed by input manufacturers who benefit from information asymmetry – one side knowing more than the other,” he adds.

Using technology to disrupt traditional business dynamics has played out in countless other industries. “Technology whittles away at the ability to profit from information asymmetry because ultimately that asymmetry doesn’t actually create more value for the customer – it just creates market inefficiency,” he says. “FBN has hit on this and that’s why it gets so much attention.”

But will it change traditional business models for the big input providers? Not necessarily.

“Many farmers are happy to pay a little more to use the ag retailer who is going to be at the river crossing when they need them,” Kolb says. “Even so, this will put pressure on input providers to change their fundamental business model, to start pricing services separately. We could see the seed business become more ala carte and intentional.”

Until now, some FBN critics viewed traditional seed and chemical company in-season support as a way to differentiate themselves over the startup. However, FBN leaders recently launched FBN Agronomy, a team of independent agronomists to provide recommendations to growers across North America.

Are traits worth it?

According to FBN data, corn yield gains from traits may be peaking. FBN farmers see only 3 bu. per acre corn yield improvement from using biotech seed.

“What it means is farmers are paying $90 a bag more to get a three bushel per acre advantage,” says Baron. “Sure, some farmers need the protection for some traits on some fields, but the importance of traits – because they have already been so effective – is less needed now than before.”

FBN’s focus on untraited seed “speaks to a broader mindset change, which is, how do I focus on profitability per acre and not just plant what the industry tells me to plant on my farm?” says Kolb. “How much traction they will get on that angle, I’m not sure.”

Meanwhile the company continues to roll out new data-based services. It’s working on technology to automatically generate crop insurance reports; Last year it launched the first multi-state health network for farmers. It launched AgriSecure, the company’s turnkey organic platform focused around a group of Nebraska organic farmers with a mission to help others make the organic transition in compliance, recordkeeping, input selection, agronomy, and marketing.

“Every new product we launch is with farmer profit in mind,” says Matt Meisner, FBN’s head of data science. “Listening helped us develop products that we believe put farmers first. Connecting growers together is what FBN was founded to do.”

Where it all started

In fact, FBN was founded five years ago when farmers began experimenting with sharing data and felt stifled by a perceived lack of transparency. University yield trials didn’t always provide apple-to-apple comparisons, and company brochures routinely claimed their hybrids were always the winner -- long a farm frustration.

“Fundamentally they didn’t trust the information they were getting from the seed companies, so they didn’t trust they were making the best decisions on seed. They didn’t trust they were getting a fair price, and that was having a huge impact on their business,” says Baron. “As we got to know them and began digging in to their problems, we said, if we can put data from two farms together, why not 200,000?”

The power of aggregated data fit well with an ‘us-vs.-them’ marketing approach for the business. “What we saw in the tech world is everyone was trying to sell farmers more stuff,” says Baron. “It was all adding incremental cost and promising incremental yield benefits, but nobody was getting at the structural problem behind low returns on the farm: a massively consolidated industry supplying farmers, and farmers acting independently so they don’t have group buying power, don’t have scale, or group knowledge.

“Farmers are cutting the checks to input companies, yet the farmers are the ones losing money.”

Even so, LaVigne believes seed companies have no reason to question conventional marketing strategies.

“To a fault, seed companies are evaluated every year – it’s not like buying a generic chemical,” he says. “That seed has to perform all the time or farmer customers will go somewhere else.”

Risk and reward

Farmers who partner with new tech startups often worry about where those companies will be five years from now. FBN leaders say the goal is to be publicly-owned.

“We want to be an independent company,” says Baron. “You see a lot of startups being sold and farmers feel burned - they either ran out of money, got shut down or sold off. We’re not for sale.”

While FBN has clearly made a splash in the market, “It’s not clear yet if that will turn into a sustained, consistent wave, or a ripple that fades out over time,” says Kolb. Adds LaVigne: “You have a young generation of farmers looking at buying inputs with services – or no services if they don’t want it. The industry was already in transition but what’s likely to change the seed industry the most is data, whether that’s coming from a seed company, a John Deere, or FBN.”

And despite all its tinkering with traditional farm input companies, agriculture needs competition in the commodity markets, concludes Kolb.

“The reality is, they (FBN) have turned a lot of heads and worried a lot of executives. Whether or not you think they have a long-term successful business model, what they are doing today absolutely benefits the farmer.”

What to know about FBN seed

FBN data has had an impact on the seed industry. But how much do you know about the seed the company sells?

Company officials tell Farm Futures that FBN leverages production and conditioning partners to spec produce seed, with numerous partners across the country.

“Our genetics come from over a dozen independent breeders from all over the world,” says FBN Head of Seed Ron Wulfkuhle. “We have 80 new sets of genetics that farmers haven't seen before in trials right now.”

Do farmer-customers know where the seed they buy from FBN comes from? Not exactly.

“Most of our breeders have asked to remain confidential to protect other relationships that they have,” says Wulfkuhle. “However, we bring our farmers closer to our breeders by sharing yield data from farmers back with those breeders, and in turn providing truly transparent information about each seed we sell.

“If we're selling a hybrid that the breeder has made available to multinationals or to other companies, our members can use our Seed Finder tool to be able to see which other hybrids have the same genetics,” he explains. “We're not going to play the game of changing the variety IDs and codes. We're actually going a step further and even showing you on our corn hybrids what the parent lines are.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like