June 19, 2015

Every year, I get 3-4 calls from folks who have had hay barns burn down. The calls almost always include the question, “Do you think I might not have gotten that hay dry enough?” It is truly tragic when it happens. The key is to control what you can control.

There is a great misconception that once hay is “dry” and baled it is plain and devoid of life. The truth is hay is never completely dry, and it is full of microscopic life. If the hay is not dry enough, those microscopic life forms can cause major problems. It’s Alive!

Many microorganisms (mainly fungi species like Aspergillus and Fusarium, bacteria, and others) are ever present in hay. They feed on available carbohydrates on the surface of the forage plants and inside the stems and leaves. The feeding results in the loss of some dry matter (DM), reduces the quality of the hay, and also generates heat.

The temperature of these hay bales, stacks, and barns can get very hot. In extreme cases, it can get so hot that the bales can catch on fire, even without a spark (i.e., spontaneous combustion). Even if the temperature does not reach these extremes, these microorganisms can also form spores. It is these spores that give the hay a moldy smell.

Nearly all hay goes through “a sweat” during the first few days after baling when the temperature rises. I conducted a study while at the University of Kentucky using two cuttings of hay wherein the bales’ temperature was tracked over time. The summer cutting, which was put up at 16 percent moisture, stayed relatively cool even during higher average ambient air temperatures. However, the fall cutting was baled a little wet (20 percent moisture) for round bales and it spiked over 140° F within just 3 days.

The heat that is generated when hay goes through “a sweat” is a side effect of the microorganisms consuming the most digestible portions of the forage, such as carbohydrates like sugar and starch. Consequently, a substantial portion of the hay could be used up during this process.

Dr. Wayne Coblentz, Research Agronomist at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service’s U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center, has conducted several experiments on the impact that hay moisture and the resulting heating of the hay have on dry matter (DM) loss, hay quality, and heat risk. He recently found that for every 10° F increase in maximum temperature, the hay would lose up to 2 percent of the DM during storage.

Since these losses are coming from the most digestible forms of energy in the forage, hay heating comes at the expense of digestibility and the concentration of energy in the forage. Dr. Coblentz showed that the TDN of bermudagrass hay is decreased by more than 1 percentage point for every 10° F increase in maximum temperature over 100° F. In other words, a good bermudagrass hay crop that was just a little too wet when it was baled might have gone into the barn at 58 percent TDN, but it likely will come out of the barn with less than 54 percent TDN if it heated up to 140 °F or more.

The "Rules of Thumb"

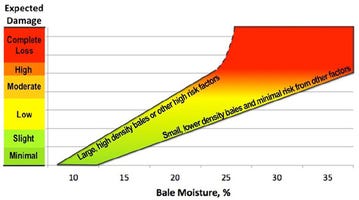

Much of the original research suggests hay moisture content should be kept less than 20 percent for small rectangular bales, less than 18 percent for round bales, and less than 16 percent for large rectangular bales. These are still good “rules of thumb,” but there are exceptions.

Consider, for example, the advances in bale package sizes and high-density baling systems that have occurred in the modern era. These denser bale packages enable the heat to build up to a higher degree. Other factors can also contribute to the extent of hay heating, including the amount of available carbohydrates in the forage crop, air circulation in the hay stack, relative humidity in the storage area, and the ambient temperature and humidity outside.

Each producer’s situation will be somewhat different because of equipment, storage technique, and climatic differences. So, within the ranges provided in Figure 3, hay growers should allow for the effect that these factors might influence which target bale moisture is right for their farm.

For more information on hay molding and heating, visit our website at www.georgiaforages.com.

You May Also Like