Native flowers and grasses are growing again in degraded prairie areas in Glacial Lakes State Park in Minnesota, thanks to intensely grazed cattle.

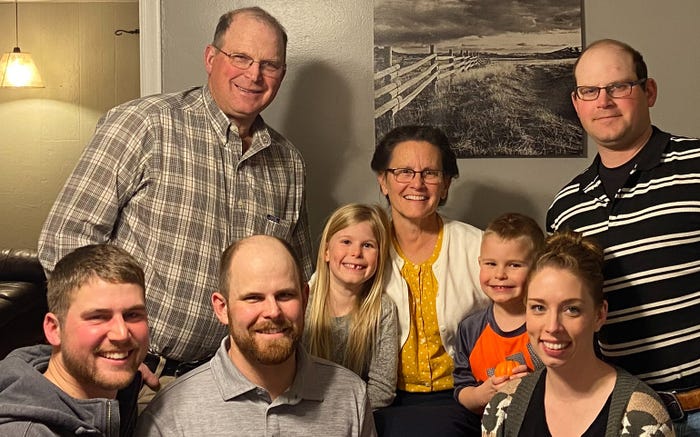

The Clear Springs Cattle Co., owned and operated by the Wulf family — parents Jim and Twyla and sons Travis and Brady — raise Simmental and SimAngus on their ranch, which borders both sides of the state park south of Starbuck, Minn. The drought in 2021 prompted them to ask park management about emergency grazing the prairie that fall.

The Wulfs, who have grazed cattle on U.S Fish and Wildlife and state Department of Natural Resources land for the last 25 years, learned through those experiences that livestock can help revive prairie.

Drought brings request to use state park for grazing

“Because of the drought in 2021, the USDA opened Conservation Reserve Program [land] to grazing, so we thought there would be the possibility to graze the state park,” Brady says.

They talked with Cindy Lueth, the DNR senior resource specialist who oversees the park, and by late September of that year, cattle intensively grazed on degraded native prairie through early October. Between 125 and 200 cattle rotated through two paddocks.

“2021 was a pilot to ensure that grazing would not cause anecdotal harm to the degraded prairie,” Lueth says. “The impacts were far more positive than negative. Based on those results, we continued edging forward with a five-year grazing plan with the Wulfs that uses a high volume of cattle for short duration, to graze more of the degraded prairie areas.”

Grazing in 2022 was spread over five paddocks using 434 acres in the southern and eastern areas of the park, she adds, adjacent to areas under grazing leases with other cooperators. Grazing was limited to disturbed native prairie with significant amounts of non-native, cool-season grasses to benefit the native flowers and grasses. Usually, park staff rely on controlled burns to stimulate flower bloom and accompanying seed production, and mowing and herbicides to manage brush and to reduce cool-season grasses.

“We observed that the grazing during the exceptional 2021 drought had effects similar to burning on this degraded prairie site,” Lueth says. “The native plants were there but suppressed, due to the cool-season grasses. The grazing stimulated them to bloom profusely, both grasses and flowers.” Then substantial spring rains fell in 2022 and by fall, the grazed area was lush with native plants.

“I harvested an unprecedented amount of prairie dropseed, an attractive prairie grass, from the grazed sites [in fall of 2022],” Lueth says. “The plants were everywhere, but the seed was only abundant where the cattle grazed.” Park staff noted a spectacular bloom of purple coneflower — a flower common to remnant prairies that is used by several prairie butterflies. Gentians also grew where they had not been seen before.

“Grazing is a great tool to help the Glacial Lakes degraded prairies move toward greater diversity, which means better habitat for rare prairie obligate species struggling to survive,” Lueth says.

Managing cattle on state land

In 2022, the Wulfs grazed 177 dry cows, with an average stocking rate of one animal unit per acre per month. They went out on Sept. 29 and came off Nov. 9. They installed single poly-wire fence with step-in posts that they remove when the cows come off the land. Lakes in the state park provided water for the cattle.

“The first paddock we grazed [in 2022] was around a large slough with a lot of forage to consume, so we left them there longer than the one AUM per acre,” Travis says. The other paddocks were higher ground with more native warm-season grasses, so the one AUM per acre has worked well on them.

The only supplement provided while grazing at the park was a Riomax lick tub for mineral and digestive enzymes and free-choice salt, which cows get year-round whether they are grazing or consuming a total mixed ration through winter and spring.

Nutritionally, Travis figures that the park’s native warm-season grasses held their nutritional value well and provided what the dry cows needed in their second trimester of pregnancy. Plus, the Riomax tub helped them digest low-quality forage efficiently.

“The dry cows maintained their body condition well,” he adds.

An unexpected plus of grazing at the park is that parasite pressure is low on land not grazed every year.

The biggest benefit, both brothers note, is that adding public land to the pasture rotation gives their own pasture time to rest.

“It also helps us to extend fall grazing late into the year,” Brady adds. “The longer we can keep the feed wagon parked, the better.”

Editor’s note: Both federal- and state-owned land can use livestock for management. State-owned land available for grazing is usually a Wildlife Management Area and federal land is usually a Waterfowl Production Area. Plus, there are different programs under both state and federal ownership that might use grazing as management, such as state parks or the U.S. Forest Service. For more information, visit Grazing public lands a win-win for farmers, hunters, a Farm Progress story published Feb. 7 of this year.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like