With over 70% of the American West, Southwest and Northern Plains categorized in D3 (severe) drought or higher since June, livestock producers are forced to try to determine how to feed their animals with short supplies or liquidate herds.

That same region accounts for one-third, or $128 billion, of total U.S. agricultural production by value. This includes 31% of beef cattle and cows, responsible for 18% of U.S. agricultural production by value, and 45% of dairy production, representing 11% of total ag production value.

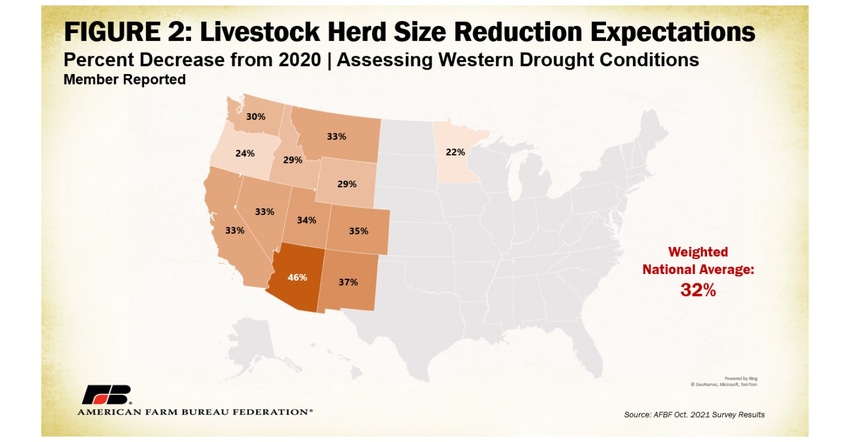

To quantify some ground-level drought impacts, the American Farm Bureau Federation’s second Assessing Western Drought Conditions Survey was distributed between Sep. 13 and Oct. 18 to state and county farm bureau leaders, staff and farmer and rancher members in the affected states.

Over 70% of the 784 surveyed producers rated the following as prevalent or higher in their area: a reduction in harvest yields; increases in local feed costs linked to drought; traveling long distances to acquire feed and forage; reduced surface water deliveries; and removing animals from rangeland due to insufficient forage, according to a recent Market Intel report from AFBF.

Widespread, low-quality or insufficient forage means farmers and ranchers must look elsewhere for feed.

AFBF shares that one Montana producer stated, “I was unable to harvest even a single acre of dryland hay because the grass didn't even get tall enough to cut. I normally cut hundreds of acres in order to satisfy most of the forage needs for my cattle.”

An Oregon producer commented, “The price of hay has more than doubled due to drought. For small operations like ours, we purchase hay. We have had to sell off stock to reduce numbers needing feed.”

In Utah, farmers report they will not be able to sell alfalfa this year because they are going to have to start feeding their own livestock earlier in the fall. The pressure of scarcity increases feed prices, which cuts deep into operational revenues.

Unproductive rangelands also led many ranchers to sell off animals early, with herd size expectations down 32% across the region, AFBF said. Producers also reported reduced weights impacting animals’ final sales value, with many traveling hundreds of miles to acquire feed at exorbitant rates.

Nearly a third of respondents rated hauling water as extremely prevalent. Access to vehicles, fuel and labor to truck water up rough terrain is limited and costly.

A producer from Colorado reported that he had to buy an old water truck to haul water to cattle on pasture as ponds that always had been used were dry for the first time ever.

Online drought tool

Farm Service Agency Administrator Zach Ducheneaux said over the summer FSA staff had conversations on the ground on how to deal with the then-spreading drought extending beyond the West and creeping into the Midwest.

During a drought tour in North Dakota, he heard growing concerns from all commodity groups including grain growers about the livestock industry and concerns on how to help them carry on. It was then he went to the drawing board to figure out if USDA may be able to offer some financial assistance to pay freight for long-distance obtaining of forage supplies.

An online tool is now available to help ranchers document and estimate payments to cover feed transportation costs caused by drought, which are now covered by the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees and Farm-raised Fish Program (ELAP). USDA updated the program this year to include feed transportation costs as well as lowered the threshold for when assistance for water hauling expenses is available.

Ducheneaux said as much as USDA would like to do same-day payments, the online tool does provide a producer what that ELAP payment might be and get a better idea for planning purposes. “We’re coming on to the really tough part of the year for a lot of producers in the northern tier,” he added.

USDA will reimburse eligible ranchers 60% of feed transportation costs above what would have been incurred in a normal year. Producers qualifying as underserved (socially disadvantaged, limited resource, beginning or military veteran) will be reimbursed for 90% of the feed transportation cost above what would have been incurred in a normal year.

USDA uses a national cost formula to determine reimbursement costs that will not include the first 25 miles and distances exceeding 1,000 transportation miles. The calculation will also exclude the normal cost to transport hay or feed if the producer normally purchases some feed. For 2021, the initial cost formula of $6.60 per mile will be used (before the percentage is applied).

The new ELAP Feed Transportation Producer Tool is a Microsoft Excel workbook that enables ranchers to input information specific to their operation to determine an estimated payment. Final payments may vary depending on eligibility.

To use the tool, ranchers will need:

Number of truckloads for this year

Mileage per truckload this year

Share of feed cost this year (if splitting loads)

Number of truckloads you normally haul

Normal mileage per truckload

Share of normal feed cost

The tool requires Microsoft Excel, and a tutorial video is available at fsa.usda.gov/elap.

The tool calculates the estimated payment for feed transportation assistance, but it is not an application. Once FSA begins accepting applications later this fall for feed transportation assistance, ranchers should contact their FSA county office to apply. To simplify the application process, ranchers can print or email payment estimates generated by this tool for submission to FSA. The deadline to apply for ELAP, including feed transportation costs, for 2021 is Jan. 31, 2022.

ELAP already covers above normal costs for hauling water to livestock in areas where drought intensity is D3 or greater on the drought monitor. FSA is also updating ELAP to also cover water hauling in areas experiencing D2 for eight consecutive weeks, lowering the threshold for this assistance to be available. Program benefits are retroactive for 2021.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like