Wisconsin farmland values in 2017 were nearly identical to 2016 values and were 3.5% higher than 2015 values, despite continued low milk, corn, soybean and wheat prices.

According to Arlin Brannstrom, faculty associate at the University of Wisconsin Center for Dairy Profitability in Madison, the statewide weighted average agricultural land value was $4,025 per acre in 2017.

Brannstrom says 9,000 more acres were sold in Wisconsin in 2017 than in 2016.

“Declining farm incomes helped to dampen demand somewhat,” he says. “A total of 90,166 acres sold last year. In 2012, a total of 147,623 acres sold. With low commodity prices expected and increased borrowing costs again in 2018, producer competition for land will likely soften this year.”

Land values, however, increased from an average of $3,365 per acre in 2012 to $4,025 per acre in 2017. That’s $660 more per acre, on average, and a 19.6% increase in five years.

“Farmland is the most valuable asset on most farmers’ balance sheets,” Brannstrom explains. “However, estimating land values is always difficult. There is nothing more unique than an individual parcel of land.”

While the state average increased slightly in 2017, there were wide variations in sale price per acre. Twenty percent of the sales were for less than $2,000 per acre, and 17% of sales had prices above $6,000 an acre.

“High-priced sales make good headlines; however, there were very few sales above $10,000 an acre,” Brannstrom says.

“We’ve seen a dramatic increase over the past decade, with land values going up double digits for several years, but in 2016 and 2017, land prices didn’t really move much,” says Dennis Badtke, chief appraiser for Compeer Financial.

“What I think has happened is people who bought land when milk and crop prices were high didn’t look at the quality of the land — they just bought it. Now the buyers seem to be paying more for quality land. And land near dairy farms is bringing more money, while land that needs to be tiled or is poor-quality isn’t selling, or it’s bringing a lot less,” Badtke says.

The good news is overall land values in Wisconsin are not going down, Badtke notes. “We’re seeing stable prices,” he says. “It’s amazing, really, that we’re not seeing any decline in land values overall, with continued low milk and crop prices.”

That isn’t the case in neighboring states. “In states like Iowa, Illinois and Minnesota, farmland values are going down. Minnesota land values dropped 4% in 2017,” Badtke says. “But those states don’t have as much dairy as we do.”

Badtke says buyers are paying top dollar for high-yielding cropland in the Dairy State.

“Corn and soybean yields have risen dramatically in the last 40 years,” he says. “The national corn average yield 40 years ago was 91 bushels per acre. Today, it’s 174.6 bushels, according to NASS [National Agricultural Statistics Service]. In 1979, the average soybean yield was 26.2 bushels. The average yield has doubled in 40 years to 52.1 bushels.”

Badtke says demand for recreational land, especially in central and western Wisconsin, is heating up.

“We have seen an increase in the interest in recreational land,” Badtke says. “The price varies quite a bit, but we’re starting to see some modest increases.”

Numbers compiled by Brannstrom illustrate what Badtke is saying. According to Brannstrom, southwest, south-central and west-central Wisconsin saw the largest percent of land sales increase in 2017 over 2016.

“The southwest, south-central and west-central districts sold the most acres, and the northeast district sold the fewest acres,” he says. “The average price per acre for bare land in the northern districts was slightly lower than 2016.”

Data collection

Several sources of farmland pricing use surveys of farmers, bankers, real estate agents and appraisers to measure land value changes each year.

“While this approach is easy to conduct, these opinion surveys can be hard to interpret,” Brannstrom says. “News of high-priced sales travels quickly — but these sales are often the exception.”

Fortunately, Brannstrom says, the Wisconsin Department of Revenue provides an alternative source of agricultural land sales data.

“A transfer return tax is collected each time a property is sold, and a transfer return form is collected with the tax. Information from these transfer return forms is the source for this analysis,” he explains.

Between 2010 and 2017, about 8,000 bare agricultural land transfer returns were used to compute weighted average sale prices per acre.

Ag land ownership structures are changing rapidly in many parts of Wisconsin, Brannstrom says.

“Up until the last decade, most property was bought and sold between individual owners or as tenants in common,” he says. “Individuals are still the most common sellers, although the percentage of acreage sold by LLCs [limited liability companies] and trusts has increased from 23% to 28% between 2010 and 2015.”

Land sold by corporations and general partnerships is only a small percentage of the total.

“As farming operations become larger and real estate ownership interests more dispersed, it is expected that sole proprietorships will become less prevalent,” Brannstrom says.

Long-term implications

High land values can be both good and bad for established farmers.

“The appreciation in land value is only realized when the assets are sold,” Brannstrom says. “In most cases, the ongoing business is neither directly responsible for nor directly benefited by changes in land values. High land values provide the retirement cushion for ‘last-generation’ farm businesses. However, high land prices make it more difficult for young farmers to get started without significant help from family members or other benefactors.”

Dairy farming in southeast, east-central and south-central Wisconsin is under great pressure from competing land uses.

“If the trend continues, dairy production will continue to shift away from these parts of Wisconsin,” Brannstrom says.

Although dairy farming is well-suited to Wisconsin’s climate, topography and infrastructure, the continued survival of a viable dairy industry depends upon access to affordable land resources.

“Unlike stocks, bonds and commodities, one can only estimate the value of real estate until a willing buyer and seller consummate a sale,” Brannstrom says. “At least in recent years, agricultural land has been a much better investment than many other alternatives. However, that may not always be the case.”

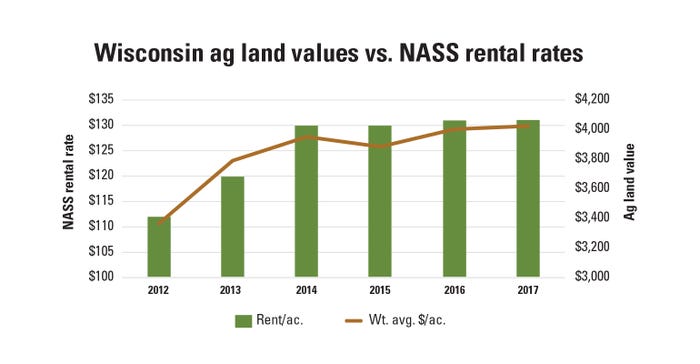

LONG-TERM RISE: Wisconsin land values increased from an average of $3,365 an acre in 2012 to $4,025 an acre in 2017.

Rental rates competitive

Wisconsin’s statewide land rental rates are reported annually by the National Agricultural Statistics Service. Even within a county, rental rates are highly variable.

“Some of the factors which affect rental rates are soil quality, field size, social contracts and demand for nutrient management,” Arlin Brannstrom says. “The 2016 NASS average rental rate was $131 per acre, which is about 3.5% of the statewide average sale price.”

There has been a high demand for additional rented land, especially from 2012 to 2014, and tenants bid up rental rates as a result, Brannstrom says. “Rental rates have remained relatively stable in recent years.”

Dennis Badtke echoes Brannstrom. “We’re not seeing some of the really high land rents that were paid between 2010 and 2014,” Badtke says. “It wasn’t uncommon to see farmers paying $250 to $300 an acre for land rent back then. Today, those rental prices are coming down. But at the same time, we’re seeing farmers who were paying $75 or $100 an acre for some of the more marginal land paying $125 or more per acre. So, some land rents are going up, and other land rents are going down — there is a lot of variability out there.

“But in general, small tracts of land probably won’t rent for as much as large tracts, because with today’s larger and larger equipment, operating small fields can be difficult.”

Brannstrom says tight profit margins likely will exist this year if yields and harvesttime prices are typical.

“In many cases, renters are not able to cover their full cost of production and must hope for above-average yields or improved commodity prices, or both. The outlook for 2018 is not encouraging,” he says.

In recent years, NASS rental rates have averaged between 2.4% and 3.4% of the average statewide ag land sales prices.

“Many more acres are rented than sold each year,” Brannstrom says. “With narrowing profitability going forward, there has been an increased use of flex lease contracts in the Midwest. Flex leases allow the owner and tenant to share the risks and rewards in good years and bad.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like