A lot of things peaked around 2013. Commodity prices. Net farm income. Farmland values.

Then it all came down, but not at the same rate.

Corn futures are off 53% since their peak of $8.43 in late 2012. Net farm income is down 50% since 2013. And Class A farmland in Illinois? It’s softened just 19% from its average high of $12,900 in 2013, coming in today at $10,500.

What’s more, most of that 19% decrease came between 2014 and 2016. From 2017 to 2019, prices have softened only slightly.

What gives?

David Klein, First Mid Ag Services vice president, believes the market is engineering a “soft landing.” That’s when the sales price of your product gets cut in half, but you don’t cut your assets in half — an important distinction for balance sheets everywhere. If grain markets come back up on a weather rally, he believes land values will creep up again in 2020.

“Quality leads to stability,” he says, noting the best soils are still in high demand because they deliver even in tough weather years, reflected in yields this fall. Class B and C soils have struggled to maintain value and won’t be as profitable in 2019. Again, that’s why Class A is in higher demand by both farmers and non-farmers, who own about a third of Illinois farmland.

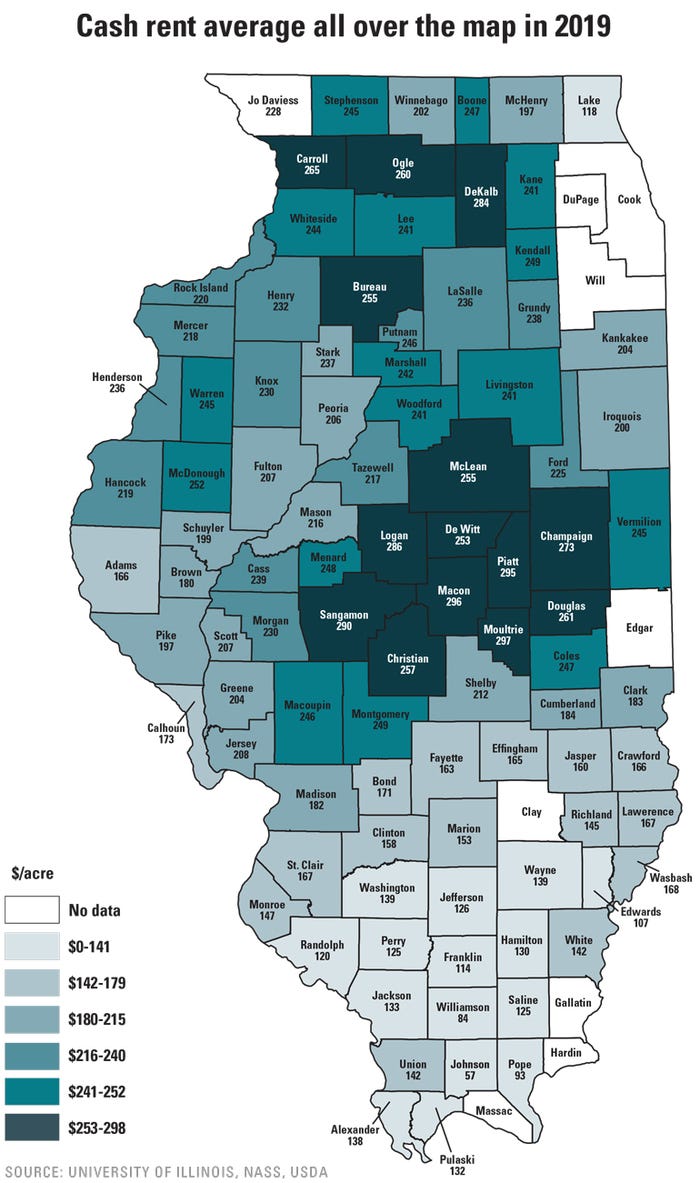

University of Illinois ag economist Gary Schnitkey sees more of the same. “I don’t see any reason to believe those prices are going to go up or down. A continued holding pattern is pretty much what we’re looking at,” he says, despite fundamentals that suggest farmland prices should come down. He does see downward pressure on cash rents in 2020 but doesn’t think it’ll translate to action.

“The ag economy isn’t good, but it’s not a disaster either. A lot of farmers are going to keep doing what they’re doing another year and see what happens,” Schnitkey predicts. “Cash rents should come down, but most farmers are going to do it again at about the same levels.”

At the end of the day, demand is holding steady from both farmers who are always looking to expand, and investors who say land is still a better investment than the stock market.

Big, global trends

It may be shocking to consider the role China plays in valuing the farmland just out your backdoor, but Schnitkey says it shouldn’t really be a surprise. The best thing to hope for at this point, relative to farmland values, is a trade deal resolution.

The White House indicates that deal is nearly solved, but Schnitkey says, “We’ve heard that before,” and adds we can’t underestimate the impact China’s African swine fever will have on feed demand. Soybean stocks are still high.

Darell Sarff, real estate broker and recently retired farmer from Chandlerville, Ill., says trade is only part of the ag economy’s problem, pointing to the administration’s ethanol waivers.

“There’s 1.4 billion bushels of corn that would have been ground if they hadn’t given away those waivers,” he says. “That’s as big of a hit as we’ve taken with the tariffs.”

Sarff remembers the work he and his farmer colleagues put in during the late 1980s and ’90s to develop Asian grain markets.

“China won’t take this. They’ll go somewhere else for grain, and we won’t get it back in our lifetime,” he says. Sarff says the U.S. needed to negotiate with China, but with more precision: “Don’t throw a hand grenade into the middle of it.”

Better balance sheets?

Schnitkey isn’t optimistic about net farm income in 2019, predicting corn yields off by 20 to 30 bushels and soybeans by 10 to 15 bushels across central Illinois. Northern and southern Illinois yields will likely be off by greater margins. Those yield reductions will knock $100 an acre off revenue. Add $20 for Market Facilitation Program payments and you still have lower incomes.

Sarff says farmers will take MFP money from the administration, noting it’s far short of what they should get from the market. “But they have to take it, because they need it,” he says.

And the million-dollar question every time the government hands out money: Is that subsidy simply propping up cash rents? There’s no doubt farmers prefer to avoid paying taxes, Klein says.

“It gets reinvested where it can most help that farmer in their operation, whether in rent or equipment,” he maintains. “MFP and other potential payments help all farms and help stabilize income and rent structure.”

We saw that in 2018, Klein says, when record soybean yields made for higher MFP payments and boosted farm profitability. This year’s payments will instead be based more on historical base acres and yields.

Schnitkey describes the typical Illinois farmer operation: owns 20% of land base, rents some reasonable land, pays some cash rents they shouldn’t. But they’re keeping up. Most haven’t had to refinance due to serious declines in working capital. Those who did refinance still have a lot of equity, which means it was a cash flow problem, not a solvency problem.

But if land values fall? Equity goes away, across the board. So while a young or beginning farmer might like to see lower prices so they can expand, anybody with land in their asset column wants those farmland values to stay high.

And at this point, everyone expects them to stay where they are, in part because demand is good — and because somebody who’s willing to pay more is still out there.

Sarff spent time on the board of a farm management firm and says every time a farm was up for rent, a half dozen guys lined up for it. Their mentality? “’I can add one more farm at high cash rent because I have this low piece from my aunt or whatever.’”

2019’s lessons

Variable leases might just be the prevailing lesson from 2019. Klein says 25% to 30% of leases in Illinois are still crop share. Of the remaining 70%, maybe 40% are fixed, 5% to 10% are custom-farmed, and the remaining 15% to 20% are variable cash rent leases. Folks who’ve been on crop share tend to like the variable lease. Newer landowners gravitate toward a fixed leasing arrangement.

Klein says farmers’ best bet if they’re feeling pinched is to talk to landowners and see if they’re willing to help you work your way through this next year. Put everything in writing, which is helpful for both parties and for the next generation, too.

For Sarff, land is an investment he’s long been willing to make. He doesn’t regret any farm he’s ever bought, but he says, “There’s a lot of farms I regret I didn’t buy.”

Sarff’s grandfather’s advice is as sound in 2019 as it was in 1970: If you get the opportunity to buy land, don’t bite off more than you can chew. It has to cash flow, it has to fit with the rest of the farm, and it can’t push debt load too high.

Sarff laughs. “It always feels too high at the time.” Still, no regrets.

TOLERANCE: “Farmers can’t tolerate low prices and low yields, and also high cash rent and high input costs,” says farmer and farm real estate broker Darell Sarff, Chandlerville, Ill.

But next year?

For Darell Sarff, it’s not hard to look around and see what may happen next. The Chandlerville farmer and real estate broker saw three big peaks in agriculture during his farming career, beginning in 1970 and ending with his retirement two years ago. He believes more land on the market next year is a real possibility.

“Farmers can’t tolerate low prices and low yields, and also high cash rents and high input costs,” Sarff observes. “There’s only so long you can tolerate that.”

Sarff believes farmers his age will get out, having grown weary of battling low prices, a cycle that’s continued since 2014. Other struggling farmers may see 2020 as the breaking year, having used up cash reserves and now eating into equity. Bankers have already told him they have clients who won’t get to farm next year — but don’t know it yet.

Still, there’s demand for land, and someone who will pay extra to get more. He recently asked a young farmer paying high rents how he could afford to do so. The young farmer told him he couldn’t; he was up to his eyeballs, “but it’s gotta turn some year.”

“I told him I lived through a lot of those years, and it takes a long time to turn,” Sarff says.

Land always has to do its job, he adds: “In our early life, we had no money. Middle, we poured it back into the farm. Now, land is part of our retirement income.”

Now compared to ’80s

Talking agricultural market cycles most always brings comparisons to the 1980s, when lower returns and high interest rates pushed land values down.

University of Illinois ag economist Gary Schnitkey says the cycle of truly low farmland values has only occurred during the 1980s and 1930s. Schnitkey says in response to high inflation in the 1970s, Fed chairman Paul Volker raised interest rates in an effort to “wring inflation out of the system.”

“He was successful but the medicine was high interest rates,” Schnitkey explains. High interest rates also caused all asset values to come down.

“And I can’t think of another asset that’s more sensitive to interest rates than farmland,” he adds. So as inflation went up, interest rates went up, then inflation came down, and land prices fell hard. Land valued at $3,550 an acre in 1981 was worth $1,900 by 1986.

Debt-to-asset ratios increased with them. “Our interest expenses were $50 to $60 an acre on some farms,” Schnitkey recalls.

This time around, Schnitkey says it’s easy to solve cash flow problems on the farm; cash rents will give.

“If people get to the point where that needs to happen, it will,” he adds.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like