Think different “Farm-level unit production costs in the Guinea Savannah zones of Mozambique, Nigeria, and Zambia generally are comparable to or lower than those in the Brazilian Cerrado…even though yields per hectare realized in the African countries are significantly lower.”Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant, The World Bank, 2009

April 18, 2014

Debates about feeding the world often come back to a simple claim that also underpins supply-demand projections: “They’re not making any more farm land.”

“The U.S., Canada, Australia, the European Union, Argentina, even Russia and China are fairly tapped out when it comes to arable land,” says Jay O’Neil, senior agricultural economist at Kansas State’s International Grains Program.

That’s borne out by the 2014 USDA Long-term Projections, which show those producer nations expanding harvested corn areas by less than 14 million acres over the next decade.

“The only major producer today with enough potential land mass for a major expansion is Brazil,” he continues, suggesting that most new production will come from yield increases.

However, some analysts argue that currently untapped potential acres could change this supply-demand equation.

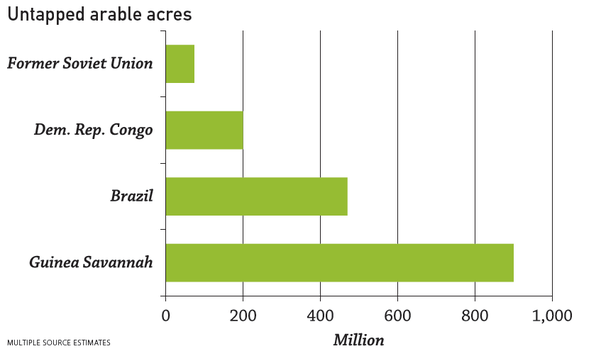

Four regions have untapped arable acres capable of producing corn. The productive potential is even greater in Brazil by double-cropping, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which can harvest three crops per year.

In the former Soviet Union, 74 million acres that were farmed in the late 1970s sat idle in 2012, roughly equivalent to total U.S. soybean acres, Ray Wyse, senior director of trading for Gavilon, told a Federal Reserve agricultural summit last year.

Brazil has 470 million in untapped potential acres, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a climate and water resources similar to Brazil’s, offers an additional 200 million acres and can produce three crops a year.

More land

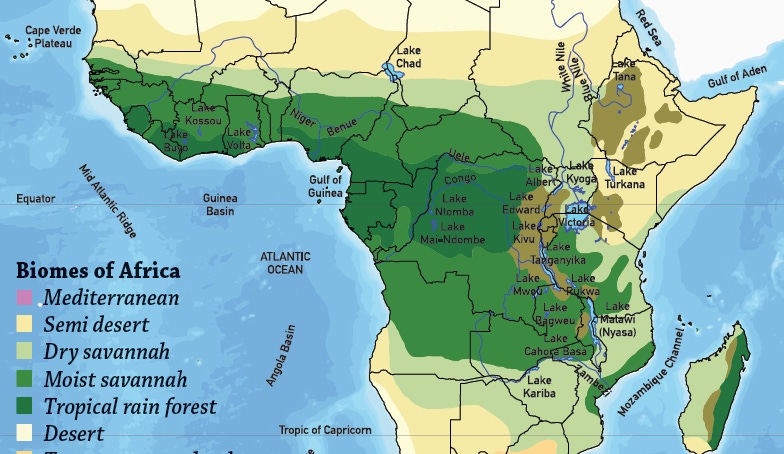

Africa’s Guinea savannah is “one of the largest underused agricultural land reserves in the world,” according to a 2009 World Bank study that found 990 million acres suited for agriculture, of which less than 10% was in crops.

Until recently, pessimistic perceptions about Africa were similar to pessimistic attitudes about Brazil’s Cerrado 30 years ago, before its rapid development as a soybean and corn producer.

The World Bank study highlighted two recent developments that have begun to change the thinking about Africa: strong agricultural growth over the last decade in many African countries and the steep rise in commodity prices, which may mean new opportunities for countries with the land, labor, and resources to increase production.

As in the 1970s, higher corn prices in recent years have prompted more competition for corn markets.

“We really started to see that in 2006, 2007, and 2008 when corn prices moved toward $5 a bushel and soybeans to $11 to $12,” says Dr. Darrel Good, University of Illinois professor emeritus.

“The common wisdom is that this new capacity won’t go away very rapidly. We saw a similar response in the ‘70s, when expansion stopped but didn’t really retreat.”

O’Neil recognizes the untapped potential but notes the challenges that must be met.

Click for larger map.

“The key word is ‘could,’” he says. “The challenges in Africa include government policies, graft and corruption, the lack of infrastructure, and uncertainty.

“You can go in there and grow the crops but getting them out is another issue. How do you get them to the export terminal? It all takes capital to finance all these components, and where will that come from in a region with turmoil?”

More bushels

Darrel Good sees productivity gains as another important factor in the productivity equation.

“We know there is land that could be brought back into production, beginning with maybe six million acres from the Conservation Reserve Program,” he says. “On a bigger scale, people are still talking about Brazil having perhaps hundreds of millions of acres that could come into production as economic conditions are right.

“On top of that, we could improve productivity with the right inputs, optimal fertilization, and better genetics. Ukraine and Russia may get the most advantage out of productivity gains. They’ve made gains in recent years but I think there is still room for more gains in yields than in land area,” Good says.

O’Neil sees the same yield potential.

New genetics driver

“A lot of places are not obtaining the yields we are in the U.S., and the biggest reason is that they’re not accepting genetically modified seed,” he says.

“What if China, Argentina, and the others embraced GMO technology? We could see substantial improvements.”

As with expanding acreage, the benefits of yield improvements may be greater for competitors whose yields are currently lower than the U.S.

Wyse believes yield growth in the U.S. has stagnated in recent years, while yields in the rest of the world have consistently grown 10 to 12% (measured by rolling five-year periods) or the equivalent of 2 to 2.4% per year as foreign countries apply modern farming techniques.

“GMO and modern farming practices have huge untapped potential to raise production outside the Americas,” Wyse concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like