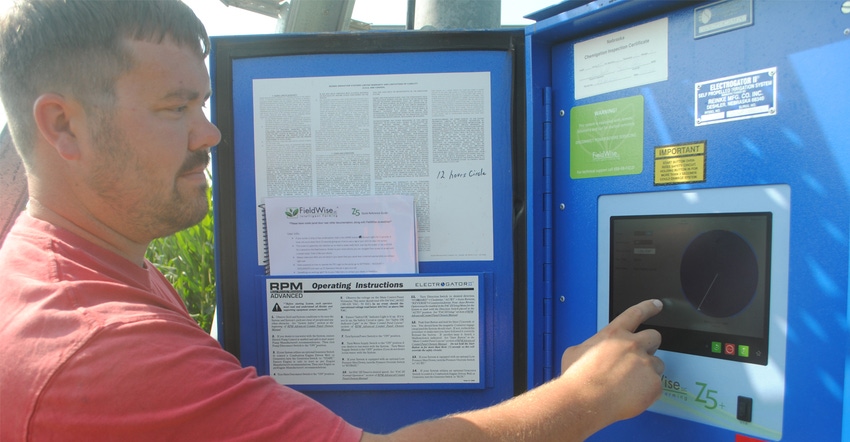

Even center-pivot inventor Frank Zybach probably could not have imagined how his original Zybach self-propelled sprinkling apparatus would evolve over the last 70 years. Brandon Christiansen of Plainview, Neb., is one of those young farmers who tries to fully utilize the latest technology for Zybach’s invention.

Farm Progress first visited with Christiansen in 2014, when he and father Rick were already veteran users of remote telemetry to monitor and operate their pivots. As new irrigation technology comes along and looks as if it could pay for itself, Christiansen is ready to adapt it to their farm.

Christiansen says his most useful irrigation-related tech over the past five years is Encirca. He says the crop modeling tool from Pioneer has helped to revolutionize nitrogen management, lower fertility costs per bushel and significantly increase irrigated corn yields.

With Christiansen’s sandy soils, he says his center pivots are the most effective tools to deliver nitrogen in-season to make the program work efficiently. “People need to utilize their center pivots more. The best way for me to put on in-season nitrogen is with fertigation through the pivot.”

The Encirca modeling program works for farmers under all management systems, but it has enabled Christiansen to fine-tune the amount of nitrogen he is placing on the crop throughout the growing season with his pivot.

Through the program, he has increased the number of treatments, particularly on sandier soils, while decreasing the amount of nitrogen placed through each treatment. The results have not only been good for yields, even on Christiansen’s sandiest hills, but also have allowed him to leave the season with little residual nitrogen in the soil, which helps protect area groundwater quality.

Encirca is a multifaceted modeling tool that allows farmers to closely manage crops through a nitrogen modeling management program, a self-prescription macro-nutrient management aspect, and a seeding analysis and prescription program for hybrids.

All three of these aspects revolve around a Decision Zones map, which is a yield management system that uses multiple data points to help producers hit yield goals. Thanks to in-field weather stations that provide current weather data to the model, the system is surprisingly accurate, Christiansen says.

The model uses predetermined data numbers and goes off past yield history, soil types, topography and water maps, as well as Light Detection and Ranging data (LiDAR), to assist in tracking infiltration rates and helping farmers make precision nitrogen decisions in the growing season. Christiansen adds irrigation logs, so pivot treatments can be calculated along with rainfall.

“We’ve done a lot of soil testing to see how close the model was,” Christiansen says. “In one instance, the soil test was just 1 pound of nitrogen away from what the model was. Of course, the model is only as good as the information you enter.”

Encirca certified service agents can provide technical assistance to help farmers get the numbers right. Christiansen notes that you have to “calibrate your mind” to the way the model works, understanding that the end result helps you run the program better over time.

Christiansen hasn’t changed harvest or irrigation equipment much since 2015. But the crop model, along with annual soil sampling and intensive nutrient management across the board, have changed everything.

He started using Encirca in 2016, and has witnessed results even with weather challenges, especially over some Thurman fine sand hills. About 30 acres of sandy hills often struggled to make 200 bushels per acre.

Thanks to timely fertigation through his pivot that the model coordinates with current weather conditions and the crop growth stage, he increased the number of nitrogen applications in the sand and across the farm, but he decreased the amount of nitrogen being placed each time. Over those hills, yields have gone up to above 250 bushels.

“I used to put on 100 pounds of liquid nitrogen fertilizer broadcast with a floater preemerge,” Christiansen says.

Because of a greater understanding of crop nutrient use, he now only floats 40 pounds of liquid nitrogen after planting, and leaves the rest of his nitrogen needs to be met with the pivot. Christiansen also attributes yield gains to a new strip-till machine that allows for placement of dry fertilizer 8 inches below the surface in early spring, and his planter that allows him to place starter fertilizer on both sides of the seed and below the seed.

“The Encirca model easily pays for itself, but with the sandy soil type on this farm, there is no way you could do this without the pivot or with any other equipment,” Christiansen says. “It tells me how many pounds of nitrogen I need in every soil type, but the timing is the biggest thing.”

After three years of experience, Christiansen attributes about 15% of the 25% to 30% overall yield gains on their farms to the crop modeling program. The other 10% to 15% gains are attributed to a greater understanding of the other nutrients and stress management of the crop.

“For instance, we had one half-mile field check that averaged over 300 bushels, which was unheard of in the past for us,” he explains.

Nitrogen efficiency has gone up. In 2013, he was using 1.2 pounds of nitrogen per bushel. Today, he is using only 0.8 to 0.9 pound. Plus, he can write his own fertility prescriptions because the model has helped him understand crop needs better.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like