Some of the proposals on the table to hack away at the federal crop insurance program are already known. And Kansas State ag economist Art Barnaby has done some of the deep analysis to detail what it could mean.

Earlier this year in its nonbinding budget proposal, the Trump administration proposed cuts similar to ones seen in the last farm bill debate, which never came to pass.

Proposals included the elimination of the Harvest Price Option (HPO), a limit on adjusted gross income (AGI) and a $40,000 limit on the government’s share of the premium.

Once a farmer hits the $40,000 limit on the government’s share of the premium, the farmer would pay 100% of the premium cost for any covered acres above that level.

The administration’s budget estimates a savings of $16.2 billion from limiting premium subsidies to $40,000 per farm. It would also eliminate the HPO, which would impact even relatively small grain farmers, according to Barnaby’s research.

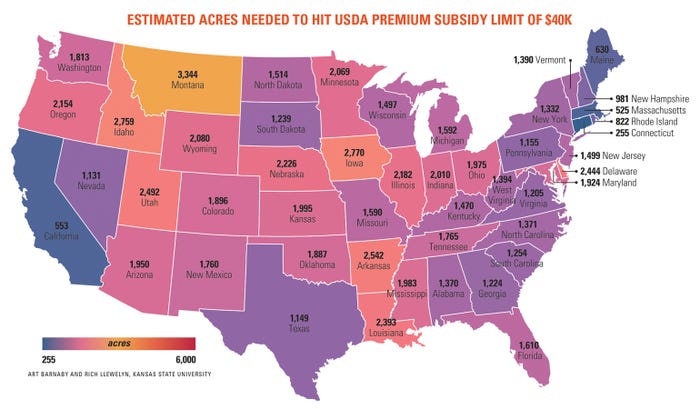

On average, it takes between 1,500 to 2,500 crop acres to hit a $40,000 subsidy cap, the government’s share of the premium costs, depending on the year and state (see map). “In the Corn Belt, it takes more acres to hit the limit because premiums are lower,” Barnaby says. But in counties in California, it could take less than 200 acres with some of the specialty crops grown.

To avoid the caps, it’s likely farmers will create new “paper” farms. This will double the paperwork for the whole system, including agents and RMA, with no new premium.

Barnaby’s research notes that some farmers may encourage their landlords to change from cash rent to crop share rent in order to stay under the subsidy limit. “Big” farmers will likely hire accountants and lawyers to create more entities.

“This will expand the administrative cost for farmers, as these entities must be kept separate for all record-keeping purposes,” he says.

Eliminating the Harvest Price Option could devastate farmers.

HPO use is high among farmers, indicating higher value among farmers. Revenue Protection (RP) has HPO, while RP With Harvest Price Exclusion (RP-hpe) does not.

The other major farm-level insurance product is Yield Protection (YP) insurance. For corn in 2016, 92% of acres insured with these three insurance types were in RP having HPO. RP-HPE was elected for less than 1% of corn acres.

A similar pattern of RP use exists for soybeans (91%), wheat (87%), sorghum (84%) and cotton (81%). Rice has the lowest use of RP at 35%.

HPO insurance has been justified as protection for farmers who forward-sell crops and for livestock producers who produce their own crops. This perspective presents HPO as a replacement-value feature when yield declines and price increases from planting to harvest.

Not all farms make forward sales and not all farms feed livestock; however, all farms have the potential to benefit from the increased coverage offered by HPO.

Barnaby notes that if harvest price wasn’t offered in 2012, payments that year would have been small or eliminated. “If it isn’t going to pay in 2012, it wouldn’t ever pay.”

Premium tweaks

Estimated acres needed to hit USDA Premium subsidy limit of $40k.

Currently, the national average farmers pay on premiums is 38%. In Illinois, farmers pay 46% of the premium. In Kansas, it is 40%. Some farmers are paying 20% or less of the premium. The rest is paid by the government.

Barnaby says you could potentially find some small savings if you put a minimum share, for example 25%, of the level farmers pay.

“If the current national average is 38%, but you make the average closer to 42% or 43%, you could do that by shifting the current subsidy rates, which would shift more over to the farmer side,” Barnaby says.

If you start shifting higher premiums over to farmers, would it reduce the number of people who would purchase coverage? No one can say if there’s a magical number.

Our latest survey found that 84% of farmers said their farm could not afford adequate crop insurance without current federal subsidies.

“If you go down too far, you end up costing Uncle Sam more money if you go back to having to offer ad hoc assistance,” says Brandon Willis, former administrator of USDA’s Risk Management Agency. “I would suggest before you make any changes, you have a lot of good analysis.”

Skin in the game

Analysis indicates that many farmers pay premiums year after year without receiving an indemnity, with about 19% of policies paying out in 2016.

Back in 2011 while gearing up for the last farm bill, there was some rumbling among corn producer groups that maybe crop insurance premiums were too high and weren’t needed in a new high-price environment. Then came the 2012 drought, and crop insurance kept farmers in business. That tune quickly changed, and farmers have dug in their support for crop insurance.

Since 1988, crop insurance policies have covered $15 trillion to guard against losses. During the same period, total premiums paid were $136 billion and total indemnities paid to farmers came to $116 billion. “This reflects the farmers’ view of crop insurance as a means of liability protection in the same way that other business owners view property and casualty lines of insurance,” says Willis.

Data also indicate that the Congressional Budget Office overstated the five-year costs of Federal Crop Insurance at the time of the 2014 Farm Bill’s passage — by nearly $11 billion. This could prove important as crop insurance proponents can claim it has already done its part in achieving fiscal savings, as the discussion of the next farm bill picks up.

Since 2008, $17 billion in budget savings have been achieved in Federal Crop Insurance through administrative and legislative policy changes.

And that age-old view that farmers in certain regions are just growing a particular crop for the crop insurance payment also doesn’t seem to hold up in real life, the economists note.

By law, Federal Crop Insurance must be administered in an actuarially sound manner, and loss ratios are down sharply, well below the 36-year cumulative number of 0.88, Willis says. Improper payments are also low, standing at 2.02%, about half of programs government-wide. And private-sector delivery costs have been reduced sharply even as Federal Crop Insurance participation levels have doubled.

This year, crop insurance will cover 90% of planted U.S. acres at an estimated cost of $3.47 billion, closely approximating the $3.13 billion it cost in 2004. Analysis finds that had Congress relied on the disaster program in place for the 1988 drought to address the 2012 drought, taxpayer costs may have exceeded $17 billion, much higher than crop insurance costs in that worst of all years.

Next: Should conservation farming practices get a crop insurance premium discount?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like