If you are a no-tiller, you may want to start scouting for stinkbugs early. That’s one good piece of advice from a recent article in the Journal of Integrated Pest Management.

Stink bugs were first found in the United States in 1996. They originated in Asia. There are over 50 species of stink bugs identified in the Midwest, with the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) gaining increasing attention.

Since 2012, the BSMB has been regularly found in Ohio soybean fields since 2012. Sometimes it has been found with other stink bugs at levels that cause economic loss. Agronomists have reported severe problems with the BMSB in Indiana, Ohio and Illinois in 2015 and 2016. As populations increase, economically significant infestations become more likely.

The abundance of native stink bug species, such as the green stink bug, brown stink bug, one-spotted stink bug and the red shouldered stink bug have been increasing for the past several years. In the southeastern United States, the redbanded stink bug is found and is thought by many to be expanding north in soybean fields.

Robert Koch, research author and assistant professor of entomology at the University of Minnesota, says the warmer winter in most of the United States in 2017 does not necessarily predict more stink bugs this growing season but it does put fields at a greater risk.

He does recommend farmers start scouting, but still feels it will be unlikely that producers in the northern states such as Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota will have to treat them this year.

“It’s an emerging problem. Add stink bugs to the list of targeted pests when scouting,” says Koch.

The reason the brown marmorated stink bug is spreading across the United States is pretty simple. They are considered good hitch-hiking pests and stow away on trucks and other equipment.

Susan Ellis, Bugwood.org

According to reports from Winfield Agronomists in 2015 and 2016, they feed on seedling corn, especially in no-till fields or fields that contained overwintered weeds or cover crops. Other native species aren’t spreading but their numbers appear to be increasing.

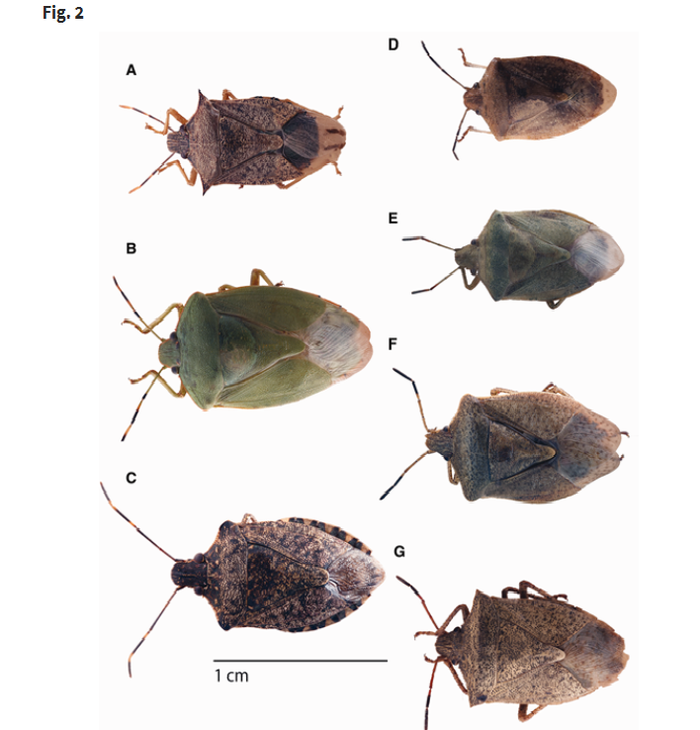

The pests don’t always share the same shape and size (see photo). They are generally described as having round or oval bodies. Some have shield shaped bodies. Some have a well-developed and often triangle shaped scutellum, piercing-sucking mouthparts and five-segmented antennae.

(Cassandra Kurtz) A.Spined Solder bug B.Green stink bug C.Brown marmorated stink bug D.Green shouldered stink bug E.Brown shouldered stink bug F.Brown stink bug G.One spotted stink bug

Scouting in corn

Farmers/scouts should get out in the field the first two weeks after corn emerges. It is critical to manage infestations early in the season. According to the Journal for Integrated Pest Management, farmers should check at least 10 consecutive plants in five or more locations per field for stink bug injury and stink bugs. In these early vegetative growth stages, examine the entire corn plant from near the base to within the whorl. For corn less than two feet tall, consider treatment if stink bugs are present on 10% or more of the plants. When injured plants are observed, consider treatment when 5% of the plants exhibit injury and stink bugs are present. Infestations of stink bugs on vegetative growth stages may be more likely to occur in late-planted fields and no-till fields. Fields planted during wet-field conditions may be particularly vulnerable if the seed furrow is not properly closed, allowing stink bug access to the below-ground growing point.

Koch says corn is also vulnerable to injury from stink bugs during ear formation through ear fill. Scouting during this period is also performed by direct examination of plants, particularly in the ear zone. Action thresholds are based on counts of nymphs (>1/4 inch) and adults of herbivorous species. Check at least 10 consecutive plants in five or more locations in the field for the presence of stink bugs. Insecticide sprays are recommended when stink bug density reaches one stink bug per four plants, from ear forming to beginning of pollen shed and one stink bug per two plants, from end of pollen shed to the blister stage.

Scouting and thresholds in soybean

Koch says farmers should scout for stink bugs as soon as pods begin to develop and continue through seed development.

Producers should scout for the stink bugs by using a sweep net or a drop cloth. Farmers with 30 inch spacing or less of soybeans should use a sweep net and those with wide-row spacing (greater than 30 inches) should use the drop cloth method to scout.

Scouting should include edge and interior areas of fields, because the abundance of stink bugs within fields can be greater adjacent to wooded habitats or early maturing crops.

If producers do find stink bugs in their soybeans, they may have to make some treatment decisions. The decisions have to be made according to the combined count of nymphs (>1/4 inch) and adults of all herbivorous stink bug species.

The levels for treatment in Midwest soybeans depend on what the end use is for the product.

According to the Journal of Integrated Pest Management, the economic threshold is presently five stink bugs per 25 sweeps or 1 stink bug per 1 ft. of row for soybeans grown for seed production. For soybeans grown for grain, the economic threshold is presently 10 stink bugs per 25 sweeps or three stink bugs per 1 ft. of row.

Koch says his best advice to all producers is to regularly scout the fields in susceptible growth stages and determine if the threshold of the stink bug is enough to warrant the use of insecticides.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like