At the end of 2021, a Kansas 4-H member turned in his bug collection project. There, pinned to the Styrofoam board, was an invasive insect only thought to be along the East Coast — the spotted lanternfly.

The young man found the spotted lanternfly — a unique spotted bug that feeds on grapevines and fruit trees — in his backyard. First detected in Pennsylvania in 2014, it sucks out the nutrients in the plants causing them to die.

“They did not find any large population of spotted lanternfly in Kansas, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there,” says entomologist Kevin Rice with University of Missouri Extension. “You’re looking for a needle in a haystack really.”

But he adds it is pest everyone needs to look for to protect the state’s wine industry.

Missouri is home to more than 1,700 acres of grapes, with more than 400 vineyards. There are 127 wineries producing more than 937,850 gallons of wine. This industry alone adds $3.2 billion to the state’s economy. According to Missouri Partnership data, the state welcomes 875,000 wine-related tourists each year, resulting in 1.16 million gallons of wine sold annually.

“We’re very concerned for our vineyards, and those that might have grapevines in their backyard as hobby crops,” says Sarah Phipps, Missouri Department of Agriculture plant protection specialist. She recently sat in on a Spotted Lanternfly Summit hosted by the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and heard from an affected vineyard owner.

A grape grower’s experience

Phipps says the owner had two vineyards, one at ground zero, about 2 miles away from where they found the initial infestation of spotted lanternfly in Pennsylvania in 2014. By 2017, his vineyard was overrun by the insect. “His vineyard was unfortunately gone,” she says.

Once this invasive insect appears in a vineyard, it is difficult and costly to eradicate. The same vineyard owner had a second location where spotted lanternfly showed up in 2017. Two years later, it too required chemical control options.

Fortunately, Phipps says research over the last seven years provides some management options; however, they are expensive.

In 2016, growers reported using 4.2 pesticide applications to rid vineyards of spotted lanternfly, but by 2018, it had increased to 14 pesticide applications just to keep the insect in check. “So that was a $54.63-an-acre cost in 2016 to a $147.85-an-acre in 2018. That’s a pretty significant increase of dollars spent,” Phipps adds.

Worse, patrons at wineries in the impacted states had to deal with the fly. The insect was on tables, in wine glasses and individuals’ hair. Many owners reported placing fly swatters at tables to help kill the spotted lanternfly. The impact to the wine industry’s tourism is also a concern.

Stories like these strengthen Phipps and the Missouri Department of Agriculture’s drive to protect the wine industry by taking a proactive approach to this pest.

Scouting for spotted lanternfly

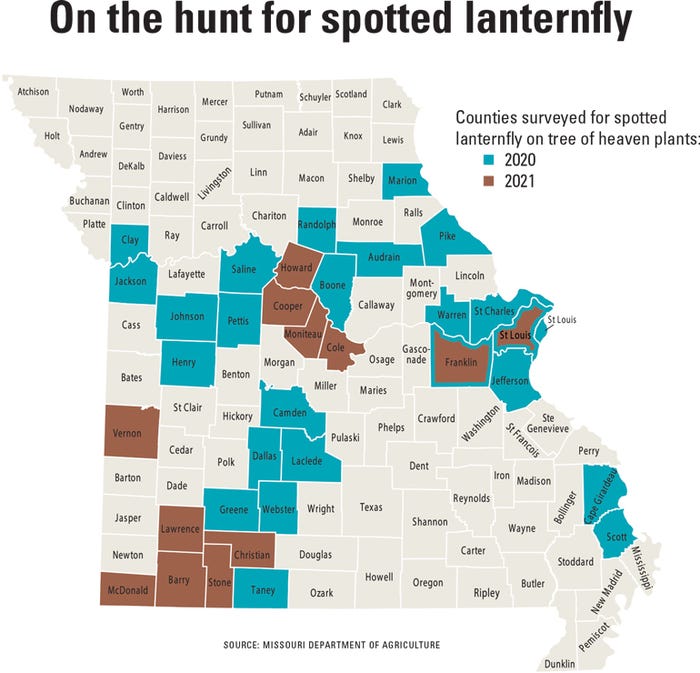

“We have surveyed a little over 30 counties,” Phipps says. “We have surveyors located across the state and have asked them to take some time and survey tree of heaven to see if there is any spotted lanternfly on those plants.”

According to Phipps, the tree of heaven is a food source for the spotted lanternfly. This invasive tree species can be found growing alongside roadways, railroad tracks or industrial buildings. Phipps also warns that the spotted lanternfly females lay their eggs on rail cars and trucks, increasing the potential for the insect to spread rapidly throughout the entire U.S. Already in Pennsylvania, trucks must be inspected and certified that they are not carrying spotted lanternfly.

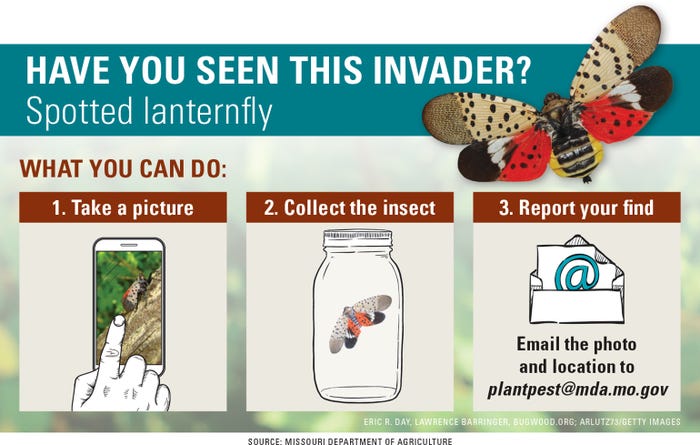

The Missouri Department of Agriculture is working with USDA surveyors to combine data sets to create a yearly account for the movement, if any, of the insect. The state is also looking for any individual, landowner or farmer to help in identifying and reporting spotted lanternfly.

Identifying the enemy

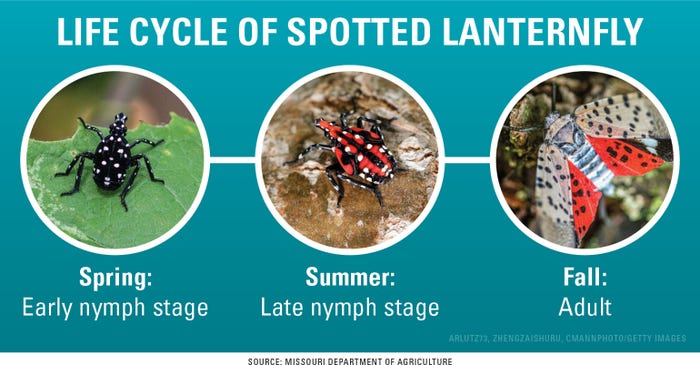

The spotted lanternfly is an invasive planthopper, similar to a large aphid, with a straw-like mouth that sucks the sap out of plants. The adult is about 1 inch long and a half-inch wide with its wings expanded.

It resembles a moth but has distinct markings. The forewing is gray with black spots, and the wing tips are reticulated black blocks outlined in gray, according to Rice. The back wings have distinct patches of red and black with a white band.

The legs and head are black; the abdomen is yellow with broad black bands. The insects during their immature stages are black with white spots, and develop red patches as they grow.

“We don’t have a whole lot of native insects that really look like this,” Rice says. “So if you see this, we ask that you call the Department of Ag and report it.”

Rice stresses that spotted lanternfly is not creating economic damage in field crops now; however, Pennsylvania reported it in soybean fields in 2017. “It’s not going to affect corn or soybeans, but it does have such an impact on the vineyards that we want to report it,” Rice says. “So if you see it, we ask that you call the Missouri Department of Agriculture and report it.”

Rice says it is important to eradicate a small population rather than let it go unchecked and grow into a larger problem for the state’s ag industry.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like