We stepped back to our 125th anniversary issue of Nebraska Farmer, published Sept. 10, 1983, to look at how soybean production has changed over the past 39 years. While much of that issue is dedicated to celebrating a milestone for Nebraska Farmer, the article that caught our attention was on Page 85, discussing considerations for planting soybeans.

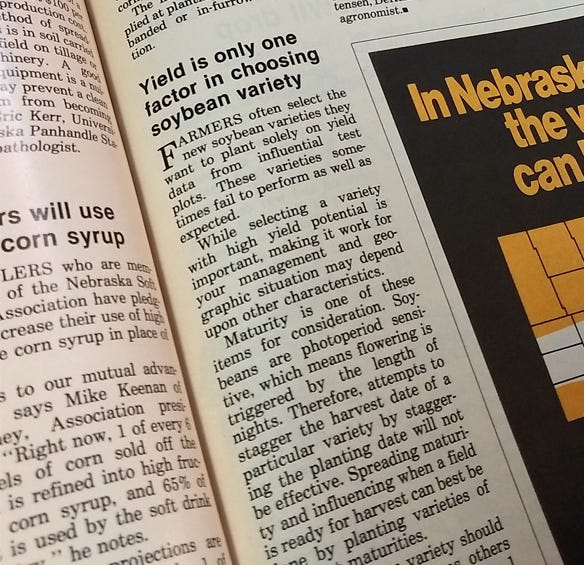

The article, written by then-DeKalb-Pfizer Genetics agronomist Ron Christensen, is sandwiched on the Crops Report pages between an ad for the Steiger Cougar IV and Cargill Seeds. It discusses basic soybean planting information, such as selecting the correct maturity, proper planting techniques, lodging considerations, plant type and row spacing. The only in-depth consideration listed is a Phytophthora rot rating for the selected seed choice.

Before the days of glyphosate-resistant varieties, weed control was left to spot-spraying selective herbicides and hand rogueing. Anyone who walked soybean fields for weeds knows that cocklebur and velvetleaf were the big invaders.

Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth were afterthoughts, and an occasional grasshopper infestation on the end rows was the biggest insect concern. Times have changed, and soybean production has gotten a little more complicated.

Yields going up

With modern challenges in soybeans, yield trend lines have increased by an average nationally of about 0.55 bushels per acre every year since 1988. It was noted in a University of Nebraska CropWatch article from 2012 that dryland soybean yields of 25 bushels per acre in that horrific drought year in Nebraska were the lowest since 1984.

Indeed, average soybean yields nationally going back to 1988 were about 27 bushels per acre, compared to 2020 when the national average was about 50.2 bushels. In spite of new pests and diseases, soybean yields have been headed in the right direction.

With many farmers trying to incorporate the soil health benefits of cover crops into their cropping systems, soybeans present a bit of a challenge in a normal corn-soybean rotation. Jim Specht, University of Nebraska-Lincoln emeritus professor, has been conducting research through Soybean Management Field Days sites, incorporating cover crops into a corn-soybean rotation, and trying to find the optimal row spacing and seeding rate under those conditions.

His most recent findings were that planting soybeans after a fall-seeded rye cover crop is terminated needs to be delayed until about May 15 to allow the cover crop to produce enough biomass. Narrow-planted rows work best under those conditions, with an optimal seeding rate of about 120,000 actual seeds per acre to offer the opportunity for the best yields.

New pests

Three years after the 1983 article appeared in Nebraska Farmer, soybean cyst nematode was first found in Nebraska. Since then, it has been confirmed in 59 Nebraska counties, accounting for most soybean-producing counties in the state. Since 2005, the Nebraska Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic has processed more than 11,000 samples from across the state, and almost one-third of those samples were positive for SCN.

In 2020, 459 samples were processed from 37 counties, with 148 confirmed positive. In 2020 alone, SCN caused about $40 million in losses for Nebraska soybean farmers. With each female capable of producing 40 to 400 eggs, an integrated approach of regular soil testing and selection of SCN-resistant soybean seed varieties — along with rotating sources of resistance in those varieties — works best in controlling SCN.

BETTER BEANS: This article published in Nebraska Farmer on Sept. 10, 1983, talks about basic considerations for planting soybeans. Challenges in soybean production have increased over the past 39 years, but yield trend lines have also gone up.

The new pest causing headaches for soybean producers is soybean gall midge. Like SCN, it is going to take an integrated approach to begin to mitigate SGM, and there is still a lot researchers don’t know. At Soybean Management Field Days in 2021, Justin McMechan, Nebraska Extension crop protection and cropping systems specialist, talked about the challenges SGM presents.

First identified in 2019, SGM is a new species to science. As of this past fall, it has been confirmed in 47 Nebraska counties and 140 counties nationwide in five states.

“The larvae fall off soybean plants and overwinter in cocoons in the top inch and a half of soil in the field,” McMechan said. “The cocoons turn to pupae in the spring and then emerge as adults.”

Larvae are found at the base of the plant, generally at the field edges, where they can girdle plants and eventually kill them.

Since being discovered, the emergence period of SGM has increased notably in the counties where it was first confirmed in Nebraska. “In 2021, the first emergence was on May 31,” McMechan said. “There was a quiet period, and then on June 4, emergence started picking up over the 14 locations that we were monitoring.”

Emergence continued in some locations until July 21. “This long duration of emergence really makes management challenging,” he said.

Once the pests emerge, they seek out the nearest soybean fields and have a presence around the base of the stems of plants within 10 to 14 days after emergence. Within 18 to 22 days, there were dead plants.

Still studying

In addition to the overwintering populations, there have been first and second generations developing within the season from the same year’s soybean fields. As tough as SGM is to manage, researchers have learned a few things over the past three or four years of studies.

Earlier-planted fields are hit first, McMechan said. While farmers may not want to delay soybean planting or plant too late, they may take a strategy of planting the highest-SGM-risk fields last to help lower larval numbers, he explained.

Researchers also are looking at applications of Thimet 20-G insecticide as one way to control SGM. “Early plantings don’t show much response,” McMechan said. “If we delay planting to the middle of May, it may have more potential impact. Planting date plays a factor.”

They are also looking at application methods that place insecticide at the base of the plant where larval presence is.

While there are more questions than answers when it comes to SGM right now, researchers in the soybean-producing states, including Nebraska, continue to look at the complexities of controlling this aggressive new pest.

It is true that soybean yields have increased since 1983, but as productivity has gone up and we understand soybean production more, there are also additional challenges that always rise up — with SGM as one of the latest of those challenges.

Learn more at the Soybean Gall Midge Alert Network website at soybeangallmidge.org.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like