October 17, 2019

Pork production is a growth industry. U.S. producers are turning out more pork per sow. On average, over the last 30 years, they’ve shipped a million more hogs per year to packers. Over those 30 years, the extra hogs have provided 2% more pork per year for consumers at home and abroad.

Seasonal and cyclical production ups and downs remain. Still, producers are capturing efficiencies by boosting pork output per unit of input. Doing more with less fuels fairly consistent growth in the industry, even in the face of sometimes challenging market conditions.

Records keep falling

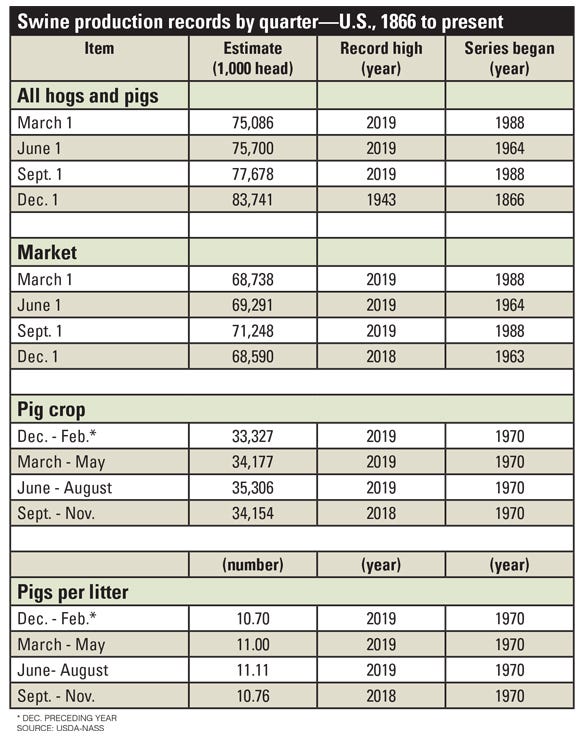

In the September 2016 Hogs and Pigs Report, USDA began providing a table with the record-high inventory estimates of all hogs and pigs, market hogs, pig crop and pigs per litter since each data series began. Not coincidentally, this aligns with the time that many inventory records began to be broken. For the first three quarterly reports of 2019, every nonbreeding herd inventory estimate has been a record high.

Most December 2019 inventories will almost certainly set records as well. The only non-record will be the Dec. 1 all hogs and pigs estimate. That record was set in 1943 at 83.741 million hogs and pigs, as farmers geared up for World War II. The December 2018 all hogs and pigs estimate at 74.915 million was only 8.826 million short of the 1943 high. The U.S. added that many hogs and pigs in the last six years.

Short- vs. long-run considerations

In the short run, how many hogs and pigs the country has is what matters. Current and pipeline supplies along with the demand situation, determine prices.

In the long run, productivity matters more than hog and pig inventories. Production efficiency of U.S. hog farms is what determines whether pork is competitive with other meats in the domestic market. Production efficiency also determines whether U.S. pork is competitive with foreign pork on the world market.

More pigs, fewer sows

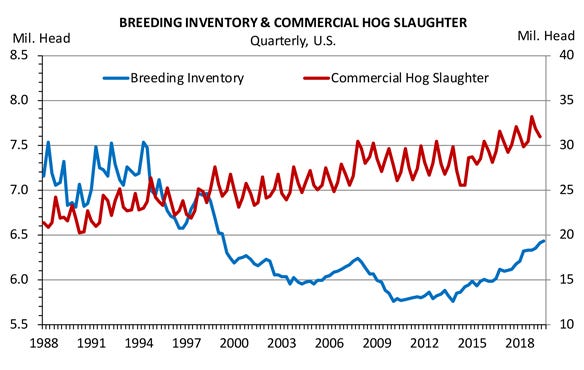

USDA’s estimate of the national breeding herd on Sept. 1, 2019, was 6.431 million head. This is the largest swine breeding herd since June 1, 1999. Still the U.S. sow herd is down more than 6% from September 1998 and nearly 11% smaller than in September 1988.

The size of the breeding herd is actually a poor predictor of future slaughter levels. Hog slaughter has kept rising as the U.S. breeding herd has generally declined. In fact, the correlation between hog slaughter and the breeding herd is –0.75 since 1988. Not only are they not very highly correlated, the relationship is actually negative. Why the negative correlation of slaughter with the breeding herd? Increasing productivity is the big driver, especially pigs per litter.

The June-August 2019 pig crop tallied 11.11 pigs per litter, up 3.6% from a year ago. This was record large for any quarter and the first time the June-August quarter was in the 11s. The March-May 2019 quarter was at 11 pigs per litter. Pigs per litter have topped the year-ago level each quarter since September-November 2014. Over those five years, growth in pigs per litter averaged 1.9% per year. Will producers set a new record for September-November this year? Probably, since sows farrowing in the fall usually have the highest pigs per litter.

Litters per breeding stall

The litters per breeding animal for the most recent quarter can be calculated as June-August 2019 sows farrowing divided by those kept for breeding inventory June 1, 2019. Multiplying this value by four provides an estimate of 1.98 annualized litters per breeding animal for the third quarter of 2019. This measure is below industry benchmarking averages and has generally plateaued since 2007.

Two factors explain why. The first is biological. Assuming a gestation period of 114 days, 21 days of lactation, and a seven day wean-to-rebreed interval puts each reproductive cycle at 142 days. That means if everything goes perfectly, a sow can produce 2.57 litters per year. Very few do. Figuring in those that do not rebreed quickly, do not breed at all, etc., results in an average of about 2.30 litters per sow per year.

Source: USDA NASS

The second reason is data-related. The survey of U.S. hog producers asks about “hogs kept for breeding” without specifying their gender or their age. The U.S. swine breeding herd is composed of boars (of varying ages kept for breeding), sows and gilts (kept for breeding).

USDA does not publish data on what share of the breeding females are sows being kept for breeding. Those data, if we had them, could show that breeding herd performance has steadily improved over the last decade. Nonetheless, this productivity factor may be at, or very near, its practical limit given recent performance.

Producers pack on pounds

Rising dressed weights are another big factor affecting the amount of pork available. Record hog prices in 2014 led to a 7.25-pound year-over-year rise in the average federally inspected barrow and gilt dressed weight. In 2015, dressed weights were down 1.8 pounds from 2014. Weights have settled in at roughly 210 pounds over the last several years.

Market hog dressed weights have averaged 210.75 pounds through the first eight months of 2019. This is 1.1 pounds, or 0.5%, heavier than last year. The weight increase nearly matches the long-term trend for weights to rise about 0.6% per year.

Why is the trend for heavier hog weights so strong? Genetics, nutrition and economics all come into play. Producers, pork packers and processors all benefit from heavier hogs ― as long as those hogs can convert feed efficiently. Efficient hogs allow producers to spread fixed and sunk costs over more pounds of output. Lower feed costs encourage producers to hold hogs on feed longer.

Heavier hogs allow packers to do the same with their fixed (plant, equipment, etc.) and quasi-fixed costs (labor really can’t be reduced and increased on a whim). Steady selection pressure for hogs that efficiently convert feed to lean meat has reduced the marginal cost of that last pound of gain, meaning more and more pounds of gain are put on each pig. Furthermore, adjustments in packer matrices have reduced the discounts for heavy hogs, meaning higher marginal revenue for those extra pounds.

One final measure of productivity is pounds of pork produced annually per breeding animal. Dividing annual commercial pork production by the average breeding herd inventory shows that productivity in the pork industry has been growing at an amazing pace. Since 1994, annual dressed pork production per breeding animal has grown from 2,469 to 4,261 pounds, up an astounding 76%.

Each breeding animal turning out more pork means the industry needs fewer breeding animals to hit a given pork production target. U.S. pork production is a growth industry. Productivity and efficiency gains are key growth drivers.

Schulz is the Iowa State University Extension livestock economist. Email [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like