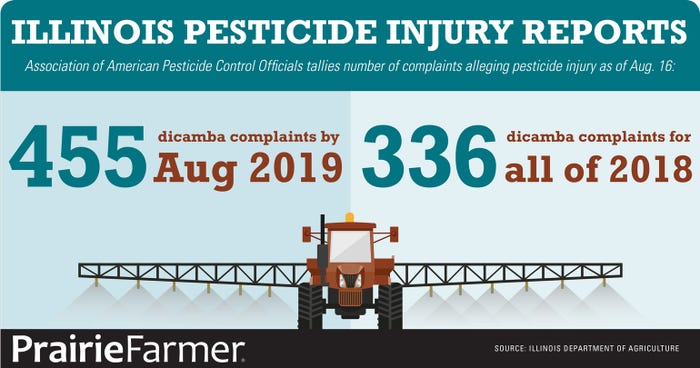

With 455 dicamba-related pesticide complaints submitted to the Illinois Department of Agriculture as of Aug. 16, the 2019 growing season has leaped ahead of 2018’s total of 336 dicamba complaints.

Aaron Hager, University of Illinois weed scientist, says label revisions have clearly not helped in Illinois, where an estimated 6 million acres of soybeans were treated with a dicamba herbicide product this year.

“We’re going to increase our complaints in the largest soybean-growing state again this year because you cannot label volatility,” Hager says.

He says higher temperatures and more fields going to dicamba-based weed control are responsible for a surge in pesticide complaints from 2017 to 2019. Illinois’ July 15 cutoff for applying dicamba on soybeans planted after June 1 — a 15-day extension granted by the state’s ag department — allowed application during warmer days in 2019.

From 1989 to 2016, there was an average of 77 ag-related pesticide complaints in a year. Thanks to dicamba, that average has surged to 406 in 2019. Like the two years prior, 2019 complaints mainly have been filed by farmers.

“The hotter it gets, the more you have — the more likely it is to volatilize,” Hager says, noting dicamba can linger in a field for up to four days and starts to volatilize around 70 degrees F. “We have never sprayed this quantity of dicamba in the state of Illinois. With dicamba’s long history in corn, we have never treated 6 million acres with dicamba in a single season like we did this year.”

Hager is worried applicators will face penalties for damage inflicted by volatilization and chemical drift.

“Why do you think we have such complicated labels? It’s so that when the inspectors go out, in many of these instances, they find a label violation. Now all of a sudden, volatility isn’t a cause,” Hager says. “But we don’t appreciate how spraying so much dicamba at once and at high temperatures can lead to symptomology downfield regardless of a label violation.”

Anecdotally, Hager reports it’s likely that many dicamba applicators first used their rigs to spray Roundup Ready, non-GMO and LibertyLink beans. They saved dicamba for last to avoid leaving behind traces, despite thorough cleaning required by the label. With bouts of rain in late June, dicamba applications were forced into a handful of warm days in July for large areas of Illinois — creating a powder keg of volatilization where leaf cupping was seen 10 to 20 days after.

“We have the highest trained people as of this winter, but when you look at the numbers here, I’m not sure training is the answer,” says Jean Payne, president of the Illinois Fertilizer and Chemical Association. While volatilization and off-label use may drive some dicamba complaints, she acknowledges that trace amounts of the pesticide result in symptomology.

“Our current system was never set up to have hygiene down in parts per million. And I don’t know how we would accomplish it,” Payne says. “We could build agrichemical facilities that are just dicamba, but when you have a label that expires at the end of 2020, no one is going to do that.” She adds that if applicators were required to keep dicamba-only rigs, they’d have to charge more than a farmer is willing to pay. Seventy percent of the farmland in Illinois is sprayed by a commercial sprayer.

Hager says he’s worried there will be yield loss for those affected by chemical drift, and in western Illinois, it’s been especially dry this growing season. The yield impacts will be severe.

While industry is pointing to environmental effects, cleaning practices and AMS inhibitors as contributors to the rise in off-target drift, Hager says chemical drift and volatilization will always happen. As more people use dicamba, more spray will be volatilized, despite “low volatility” blending and coarser nozzle sizes.

“I can take you to a hundred different places in this county where that ‘environmental effect’ somehow stops at a property line or a fence,” he concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like