Many people gush over the farm profit potential surrounding hemp. But Indiana farmer Don Zolman has a word of warning: “Buyer beware!”

Zolman, who planted 46 acres of hemp in 2019, says one thing he found as a common theme to all the hemp hype was a “gold rush” mentality.

“This market is like the Wild West. I spent a lot of time trying to sort out who to deal with and what to believe, and I still got burned to an extent,” he says. “It wasn’t a third degree burn, more like a really bad sunburn. I’m hoping that is the extent of the damage.”

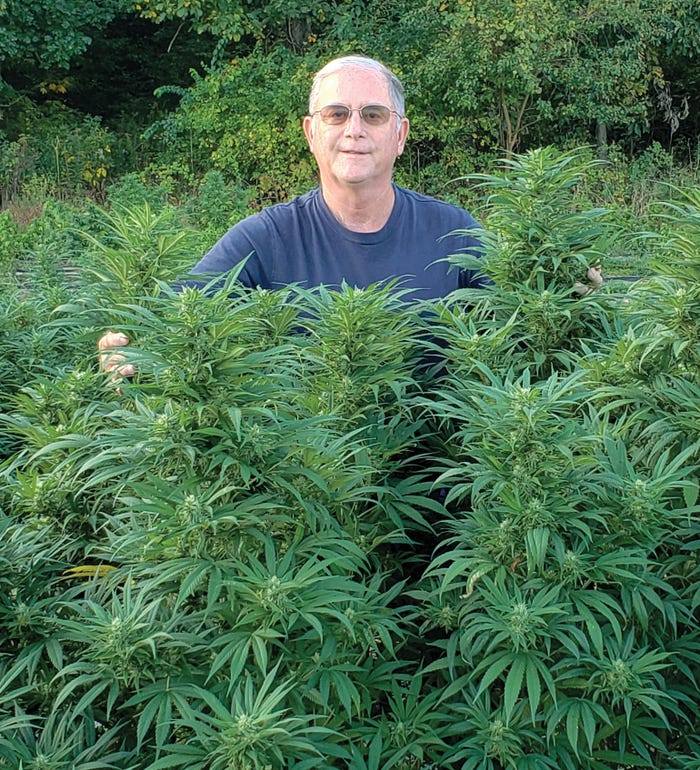

Don Zolman says farmers need to beware before planting hemp.

Zolman was one of thousands of U.S. farmers who dove head first into planting industrial hemp, sending planted acres soaring from an estimated 78,000 acres in 2018 to 285,000 acres in 2019, according to estimates from Brightfield Group. Thanks to the federal legalization of hemp-derived cannabinoids through the 2018 Farm Bill, farmers hope to capitalize on this burgeoning market. And eventually they still might. Yet, many found unreliable seed, inconsistent end users, unknown high labor needs, high THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) levels that left crops worthless, not to mention an unfriendly regulatory environment.

Market potential

Industrial hemp could eventually be used in thousands of products. Farmers looking to grow the crop seek an end product in three areas: grain (seed or hemp oil), fiber (stalk) or CBD (CBD oil). And it’s important to know the end market before one goes looking for gold.

CBD looks to be the market driver for hemp, but also poses the greatest risk. Brightfield estimates that 87% of the hemp grown in the U.S. is expected to be used for CBD processing in 2019. The research firm estimates that CBD could potentially lead to revenue of over $40,000, compared to less than $1,000 per acre for corn.

Brightfield anticipates the hemp-derived CBD market in the U.S. to top $23 billion in revenue by 2023. Brightfield has one of the most ambitious outlooks on CBD sales, but suggested growth is undeniable, especially if the Food and Drug Administration confirms favorable safety and health benefits of its use.

The Midwest Hemp Council led the hemp growing season in Indiana through the 2019 Indiana Hemp Cooperative Research Trials. The Cooperative includes 40 licensed farmers grew approximately 2,400 acres for seed, fiber and CBD and worked to secure contracts for the fiber and seed. Jamie Campbell Petty, executive director of the Council, says many farmers not involved in the cooperative were enticed to plant cannabis for CBD oil due to the allure of large profits. Yet most of those growers had no contract in place to purchase their crop or if they did, the buyer is not meeting the contractual obligations.

Campbell Petty herself takes CBD daily and believes in the product and the crop. She states, however, that FDA guidelines are required to ensure quality, through transparency and traceability of the product when it hits the shelf. For the grower, it is important to recognize that CBD is not traditionally grown as a row crop, but instead as more of a horticulture crop. Risks include lack of quality genetics, fertility and what’s going to make the plant “hot” with high THC levels.

Campbell Petty cautions this is a new crop, and an industry in its infancy. “This is not a way to get rich quick or to save the farm,” she warns. She believes in the future, and the opportunity for farmers to gain a diversified income stream. But recognizes it will take time. Due to the newness of the crop, it requires time to build out infrastructure and solid supply chains.

Fiber on the other hand offers an easy transition to the hemp market, she says. It is similar to growing hay: it can be drill planted, harvested using a sickle bar and bailed similar to silage. Zolman adds that fiber is the easiest of hemp types to produce and someday may hold the greatest promise for more acres, maybe even similar to current day plantings of wheat.

“The problem is that as of today, the market is almost nonexistent,” Zolman says on the fiber side. “We have to remember that just a year ago, this crop was illegal in most states. It will take three to five years to get processors and receiving facilities up and running.”

Campbell Petty sees fiber as the “long-game” for the industry with the thousands of promising uses, especially when it comes to replacing petroleum-based products from everything ranging from car panels to replacing paper products and clothing lines. Hemp addresses many of the concerns of a generation with growing awareness about the impact on the environment.

In a recent report, CoBank details that grain/seed hemp currently has a better rate of return than fiber but less than CBD. Grain/seed hemp has more stable risks and long-term prospects than hemp fiber or CBD, but not the growth potential of either. Hemp seed is claimed to be a super food that is high in fiber, protein, omega-3s and essential fats. Hempseed cake could potentially be a viable protein source in animal feed once it is approved by the FDA as a commercial feed ingredient. Its protein content is typically cited at around 30%, which is less than soybean meal, but studies show hemp seed is a more digestible protein.

Campbell Petty shares farmers who have experience growing an oilseed, such as canola or sunflower, or who have grown popcorn or food-grade products, could easily substitute hemp for seed or grain use to diversify their operation.

Crystal Carpenter, CoBank senior economist for specialty crops and author of the report, shares that hemp for fiber and grain can allow farmers to try larger acre subsets, and also allow some crossover in utilizing similar harvesting and planting equipment as traditional crops. Also, it is less labor-intensive than hemp grown for CBD.

Risk-tolerant

“Don’t plan on this crop saving the farm,” Zolman warns. “It could, however, put you out of business if you aren’t careful.”

He planted 2,220 clones per acre at $5 per clone totaling a $11,000/acre investment. So, that’s a $110,000 investment in just ten acres - just for the plants. Then one must consider high labor requirements that require intensive weeding and potentially hand harvesting, as well as limited herbicide options.

CoBank found that for a farmer taking on the majority of the production risks and costs (which can be extremely high), 2018 CBD prices commonly reported in the range of $3- $5 per percentage point of CBD concentration (within the dry flower). For 10% CBD yielding 2,000 pounds of dry flower per acre, that equates to $60,000 to $100,000 of gross revenue per acre (before expenses). While most in the industry do not expect these prices to last and prices will come down significantly, plenty of people are looking to take advantage of the short-term opportunity.

Carpenter says it is wise to look to smaller acre subsets until more is known on this new crop. “Don’t risk more than you can afford to lose,” she says, adding many went too big, too fast.

Matthew Fitzgerald, who farms 1,700 acres of organic corn, soybeans, edible beans, wheat and alfalfa with his father in central Minnesota, added 110 acres of hemp to his operation in 2019, yet only harvested 70 acres due to poorly drained soils and difficulties with seed bed preparation.

He says it’s a balancing act right now of those entering the market for the reward opportunity and associated risks. “Anyone who thinks it’s going to be a gold rush on very large acres should be very cautious,” Fitzgerald says.

Certain industrial hemp growers will be able to obtain insurance coverage under the Whole-Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP) program for crop year 2020. USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) is now offering coverage for hemp grown for fiber, flower or seeds, which will be available to producers who are in areas covered by USDA-approved hemp plans or who are part of approved state or university research pilot programs.

Growing pains

Campbell Petty says the Wild West mentality is clearly an issue with seeds with limited genetics considered reliable and stable. Many are from Canada or out of Colorado or Oregon and then tried to adapt to the Midwest. She says it will be important to establish genetics best-suited for Midwest climates.

She adds whenever a farmer picks a lane – whether grain, fiber or CBD – he or she should make sure to understand exactly where the seed is coming from and what that seed is going to do. Authenticity of the seeds’ history, germination and feminization all are paramount.

Zolman admits the quality issues he experienced with his clones in the 2019 planting season soured him a bit on the process. He says the company supplying him the clones overpromised and underdelivered.

“I suggest whoever you decide to work with, you check them out completely,” Zolman says. “The quality of what you plant will make the difference between success and failure.”

Today no third-party certification exists for the purchase of plants, but Zolman said it would be beneficial to protect buyers of clones from getting ripped off.

Zolman went as far to start his own CBD company – Zemp Farmaceutical. After harvesting and processing, he will have his own product under his own label. “I did this to ensure quality control and that people were getting what was on the label.”

New crops require additional research and understanding of best practices.

Fitzgerald says he plans to plant a similar amount of acreage in 2020, but on higher quality ground that has better soil drainage. He plans to focus on seedbed preparation and improved fertility. Campbell Petty says sandy soils have had better success. The max for seed planting is ¼” depth. Soil sampling is also helpful to determine the needed levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Research continues to evaluate whether excess nitrogen pushes levels of THC too high, which could then deem crops to be destroyed.

Regulatory framework

At the end of October, USDA released a rule which outlines requirements and regulations for U.S. hemp production and covers both states (with and without USDA-approved plans) and Indian tribes. Hemp is currently legal to grow in 46 states, and all of those states have indicated they will submit a plan to the USDA.

Whether operating under a state plan or the federal plan, the rule provides much-needed guidance to growers, processors, manufacturers, and transporters of industrial hemp on issues of sampling and testing. Carpenter explains there are still some unknowns, especially as it relates to THC testing. USDA requires that THC levels have to be under the 0.3% limit or the plants would have to be destroyed. Questions remain if the suggested requirement of testing 15 days after harvest is at the start of harvest, or when harvest is completed, and what if it is sent to a lab but not tested in the needed timeframe.

Despite the widespread presence of CBD in the market, it is not technically approved by the FDA for food, beverages or dietary supplements. FDA currently is working on its long-term evaluations of CBD for safety, dosage and validation of efficacy.

“In my mind, that is really the lynchpin of long-term CBD potential,” Carpenter Petty says. She says with FDA’s approval, many companies, including larger ones, currently on the sidelines will quickly jump in the market. If FDA does not offer its full approval, she expects a significant pullback in the market.

Supply chain collaboration

One of the major challenges is building out infrastructure, and at the right pace. Agriculture is well-known for overproducing, so it’s important to line up the supply chain in a way that allows the full potential for the promise of the “new” old crop, says Campbell Petty.

Kentucky has three extraction facilities in Lexington, but all are large and in financial trouble. In the Midwest, Campbell Petty is hoping to bring people together to start a small processing facility that local farmers can service and then eventually expand. “Everyone should be at the table together building this out together,” she says.

Fitzgerald adds there’s an important role farmers need to play, similar to the infancy of the ethanol industry. “I think fundamentally unless farmers control the chain, they’re going to get screwed in the end.”

Farmers can come together and cooperate on processing and harvesting, as well as the seeds. It’s important to get in on this early, to offer the potential for farmers to capitalize on the new market opportunity, says Campbell Petty.

“This market opportunity should be shared by neighbors and farmers who have the same integrity. Otherwise this gold rush mentality is going to burn people,” he says.

Check out these other stories on hemp.

USDA rules on hemp pose challenges for growers

How to grow, sell hemp for CBD oil

1st-time CBD growers look for buyers

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like