October 28, 2019

This year’s harvest has been a test of management and patience — as was this year’s planting and growing season. Some corn and beans were planted early; many fields were planted a lot later than normal due to the wet spring. There’s a wide range of maturity and moisture content in grain this fall.

“The 2019 planting and growing season had periods of both stress and favorable crop growth. The big issue this fall is variability — in yield, test weight, grain moisture and quality,” says Charlie Hurburgh, grain quality expert and professor in charge of the Iowa Grain Quality Initiative at Iowa State University.

The first frost this fall nipped Iowa on Oct. 11-13. For much of the corn and soybeans, that frost ended the growing season. The later-planted corn, especially corn planted in June, has significantly lower test weight. Corn that reached black layer by first frost wasn’t affected as much. Soybeans hit by frost prior to reaching maturity are coming out of fields wet, green and, in some cases, mushy.

Guidelines for handling, drying, storage

“Corn and soybeans hit by frost before full maturity should be stored and managed separately from crops that reached maturity prior to frost,” Hurburgh says. “Separate your grain as much as possible. Keep the lower quality grain separate from higher quality grain right away at harvest before you put it in the bin.”

Hurburgh offers the following observations and recommendations for harvesting, drying and storing this fall’s crops.

Corn quality concerns. Test weight, an indicator of corn maturity, is averaging 54 to 55 pounds per bushel this year in many cases, less than the long-term average of 56 to 58 pounds. Lower test weight means more breakage in handling, shorter storage life and often higher drying costs per unit of water removed. On a weight basis, feed value and digestibility do not decline significantly until test weights fall below the mid-40s. Check the test weights from each field and hybrid, and sell the lightest corn first.

When you dry corn, test weight should increase about 0.2 pound per bushel per percent of moisture removed; increases less than that indicate immaturity. Early death of corn plants from frost typically creates low-test weight grain that doesn’t increase much during drying. The detrimental effect of low-test weight is primarily on storage and handling. More fines are created in handling, which increases storage issues by restricting airflow.

Feed value. If the low-test weight grain is formulated by weight and not volume, feed value isn’t greatly reduced. On a weight basis, ethanol yields shouldn’t be affected unless there has been spoilage.

Variable grain quality means more variability in storage. Try to even out the moisture of corn going into dryers by not mixing grain from areas of fields with large differences in quality. Dryers will not even out such variable corn. Grain elevators will have more difficulty controlling uniformity than farmers who are drying on the farm, as the quality of corn in deliveries to elevators can’t be controlled.

Corn ear mold. There are reports of mold damage on ears in the field this fall, making it important to scout fields prior to harvesting. The penicillium ear rot is more prevalent than usual in central Iowa; Fusarium ear rot is also prevalent. Most ear rots are associated with insect damage to kernels.

Before harvesting fields, scout the field where insect activity was high. Other molds observed include trichoderma, cladosporium and gibberella. The Crop Protection Network has a publication describing ear rots, symptoms and signs.

Moldy ears bring a risk of mycotoxins and negative health effects for livestock and humans. Information on mycotoxins is available from the Iowa Grain Quality Initiative at iowagrain.org.

Safe storage time for corn, beans

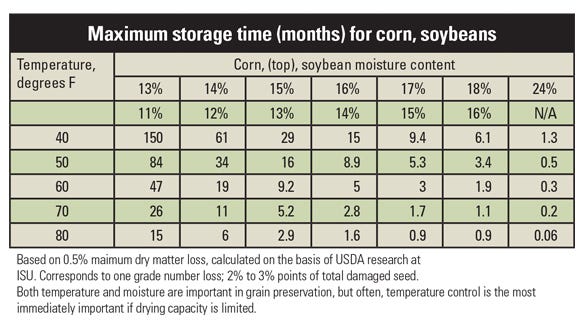

The table shows storage life of corn and soybeans at varying moisture and temperature conditions. At the end of the allowable storage time, grain will have lost about 0.5% of its weight and will have increases in damaged kernels enough to reduce its grade by one number, which generally would trigger damage discounts in the market as well.

“With lower test weights, even in fully mature grain, these storage times shown in the table should be reduced,” Hurburgh says. “Experiences from previous low-test weight, high-moisture years suggest that at 52 to 53 pounds per bushel, storage life of corn is about 50% of the numbers in the table.”

To safely store grain through winter, you should dry good-quality corn to 15% moisture and soybeans to 13%. To store into the warmer summer months, dry corn to 13% and soybeans to 11%. Dry low-test weight corn and corn with damaged kernels to 1% lower moisture content than normal. High-temperature drying should be limited to 160 degrees F for frost-damaged corn and 130 degrees for soybeans, to limit damage in the dryer.

Low-temperature or natural air grain drying should be limited to 21% moisture corn or below. Natural air drying is typically not as useful after late October, he notes. When average daily temperatures cool to below 40 degrees this fall, focus on getting your grain cooled for winter storage, aerate during winter as needed and continue drying when temperatures rise in spring.

Remove foreign material

Always remove the center core of corn and soybeans from bins, as quickly after harvest as possible. This takes out the fines and foreign material that are sure to be storage issues later in the year. Also, air diverts around the foreign material in the grain, which prevents cooling. Mycotoxins are often higher in fines and broken, damaged kernels. Removing the center core can improve grain quality and have fewer mycotoxin issues in the remaining grain.

Pulling the center core from bins filled with corn or beans will help in delivering quality grain to market. Loads are discounted at the grain elevator based on a percentage of foreign material present. For example, 2% foreign material in soybeans means 2% less weight marketed but 2% more material hauled in.

Due to late planting and rainy weather, there were more escaped weeds this year. More weeds mean more foreign material. Shorter plants with pods set close to the ground adds another concern this year. There’s a tendency for farmers to run their bean header low to try to get as many pods as possible into the combine. Thus, more dirt and weed seeds are showing up in harvested beans this year.

What to do with frosted beans

Soybeans hit by frost should be stored and managed separately from other soybeans. “Frost damaged beans will be wet and green and mushy,” Hurburgh says. “Frost lessens the shelf life of soybeans, so it’s best to leave those beans separate and let them dry down on their own.”

Don’t harvest frosted beans and sell them right away. That causes concern among processors due to color standards. A lighter-green soybean likely fits within the standard. A darker green suggests damage. Green soybeans make green soybean oil. The oil then must be refined more heavily to remove the greenness and bitterness. Farmers should store green beans in a bin and aerate for several weeks. “The greenness should subside,” Hurburgh says, “and the green damage issues shouldn’t be as acute.”

More information is available in ISU Extension publication Frost Damage to Corn and Soybeans, PM 1635.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like