Good hay is likely much cheaper than poor hay if you also consider the cost of supplement for cattle.

This appears an obvious issue in the beef industry because people still talk about "cow hay," or say that really poor hay is "good enough for the cows." If they referred to the low end of an alfalfa crop, then it would be plenty good, maybe too good, but that's not normally the topic of such conversations.

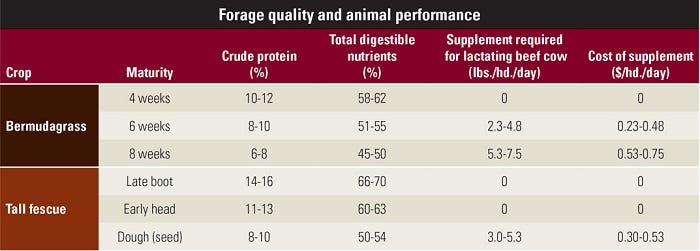

A good example of how slightly better hay can really pay -- or save it -- was calculated by Dennis Hancock, extension forage agronomist at the University of Georgia. Looking only at fescue and Bermudagrass hay, he calculated a small improvement in harvest timing, therefore in forage quality for these forages, could save 25-75 cents per cow per day. See the chart with this story for those figures.

Perhaps of particular interest in this chart is the cost of being just two weeks late harvesting bermudagrass hay. Most bermudagrass is at the optimum mix of quality and quantity at four weeks, but waiting two more weeks adds tonnage and bragging rights at the coffee shop. In this set of figures, Hancock estimates that extra tonnage also costs 23-48 cents per day in supplement for a 1,200-pound beef cow of average to above-average milking ability in her first three months postpartum (lactation).

Another way of measuring the value of nutrients in hay is what people will pay for those specific nutrient levels, such as crude protein and total digestible nutrients. In a study from the mid 1990s in Oklahoma, researchers measured the price paid by dairy producers for several components in a large hay market. Generally, they found these relationships:

One unit increase in RFV = $0.32/ton increase in price

One percent increase in TDN = $1.65/ton increase in price

One percent increase in CP = $2.55/ton increase in price

One unit increase in NDF = $1.63/ton decrease in price

One unit increase in ADF = $1.64/ton decrease in price

Of course, beef cattle only need high levels of energy and protein during lactation, and to a lesser degree during the last one-third of pregnancy, but these prices are still an interesting examination of hay nutrient values, despite being 20 years old.

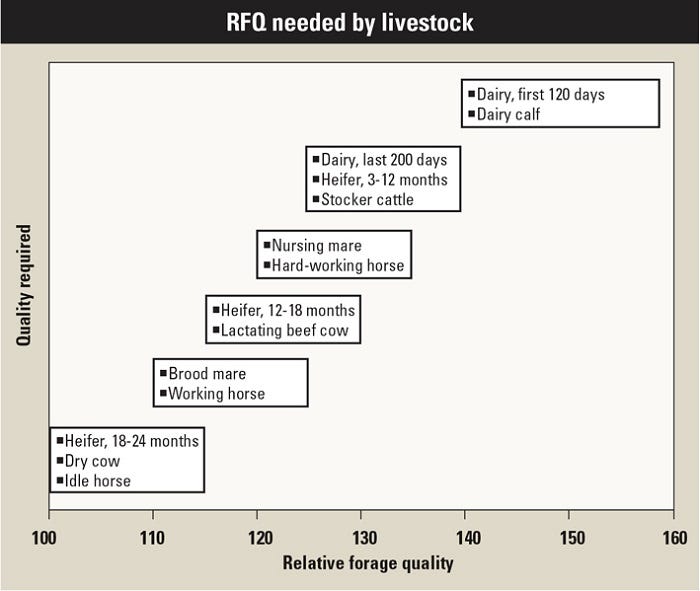

In his publication, Hancock talks about matching the relative forage quality (RFQ) of your hay to the needs of your livestock, then supplementing to make up any deficits.

Relative Forage Quality (RFQ) is a good way to classify the overall quality of forage for whatever class of livestock you are feeding. It is not, however, a ration-balancing tool.

"Animal performance ... is driven by the number of calories the animal consumes," Hancock explains. "Although protein, minerals, vitamins, and water must also meet or exceed the requirements for the desired level of performance, the most limiting factor is the amount of digestible energy that the animal consumes."

This says a high-quality forage contains plenty of digestible energy, which also will be eaten in large amounts, meaning it supports good dry-matter intake. This combined measurement of forage is encapsulated in RFQ.

The ranges in the blue chart illustrate the RFQ values most likely to minimize supplementation, Hancock explains. However, if a sample of forage falls within these recommended ranges it does not mean it will provide all the nutrients needed for the livestock being fed. RFQ isn't intended to develop a ration, but to offer a reasonable first approximation about whether a forage will provide a cost-effective base for the diet supplied for the class and production phase of animals being fed. If you are already supplying them with hay it is probably a good idea to get from that hay as much of the needed nutrients possible. If you put up your own hay, then the costs you incur every year and long-term by owning your equipment suggest higher-quality hay is a better return on your "investment" than is poor hay.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like