Anything can happen during the growing season. Mother Nature can’t be controlled. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a backup plan, especially for your forages.

Warm-season annuals can be a good backup option for feeding cows. Just be sure you’re growing something that will suit your area and needs, says John Bernard, emeritus professor of dairy science at the University of Georgia.

“You’ve got to do your homework on varieties,” Bernard told attendees of a forage discussion at World Dairy Expo. From his perspective, a complete forage program has multiple options, including warm-season ones. They can be handy if you didn’t get the yield you were expecting from your spring forage, if the weather is very dry, or if you have delayed planting of corn silage.

“Maybe you didn’t get quite the yield from your forage that you thought. … You may look at a summer annual to fill in the gap, but one of the big things is that over the past 10 years there’s been a lot more varieties developed that can deliver a high-quality forage,” he says.

One of the advantages to warm-season annuals is that they are more efficient at using water than corn silage. Bernard has found that forage sorghum is 51% more efficient at using water, while brown midrib (BMR) sorghum is 18% more efficient than corn silage.

Part of the reason is plant root structure. Corn doesn’t grow as well deep in the soil, or as plentiful as sorghum or millet, Bernard says. When you get into cost of seed and fertility, he says that it takes about same amount of nitrogen to produce comparable sorghum tonnage, but slightly less potassium (potash). Seed cost, compared to corn silage, is cheaper, but there is much more variation in yield and quality.

"You got to do your homework on varieties," Bernard says.

Improved traits

University and industry breeding programs have helped develop warm-season annuals that are higher quality and have improved traits, Bernard says.

A big breakthrough was two decades ago when researchers identified the BMR gene in some warm-season annuals. It’s a natural mutation that leads to less lignin in the plant.

“Think of it [lignin] as mortar that holds brick together,” Bernard says. “It interferes with digestion. So if you lower it, it interferes less with digestion. That’s how a cow gets more energy consuming a BMR variety vs. normal.”

But the big trade-off is a 10% average yield reduction. You’ll also likely see more lodging, and these BMR sorghums are not as drought tolerant. However, BMRs that are brachytic dwarf will have less lodging because of the shorter stem.

A growing number of photosynthetic sensitive varieties have a delayed maturity but will grow quickly and provide lots of tonnage, but quality will not be as good.

“So if you’re looking for high yield and that’s your criteria, these have a place there,” Bernard says.

Can they produce?

Bernard says growers should think of warm-season annuals as part of a complete forage package that takes into account soil fertility, weed control, water supply and the length of growing season. In his native Georgia, many growers will go with corn on irrigated land, but grow sorghum on dryland because it can handle heat and drought much better.

Some warm-season annuals only need 60 days to grow, while others take up to 120 days to mature.

They don’t have as much starch as corn silage as they are higher in protein. So what’s their impact on production?

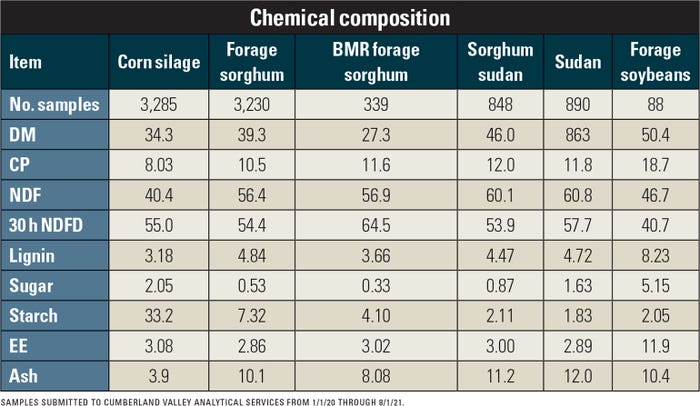

Here’s a look at the chemical composition of some popular warm-season annuals in comparison to corn silage based on samples submitted to Cumberland Valley Analytical Services from Jan. 1, 2020, to Aug. 1, 2021.

Bernard pointed to a trial done in Nebraska in 1999 where researchers evaluated a diet of 65% forage from either formal sorghum, BMR forage sorghum, alfalfa or corn silage, and 35% concentrate.

The diet with corn silage did the best in terms of dry matter intake, milk production, fat and protein. When the diet was balanced for nutrient content with 17.5% alfalfa silage, plus 35.3% from either normal forage sorghum, BMR forage sorghum or corn silage, the results were much different.

“The key difference was all rations were balanced rather than just substituting one forage for another,” Bernard says. “You can’t just substitute for corn silage as they do not provide the same nutrients.”

Dry matter intake, milk production, fat and protein were all higher, although by statistically small numbers, in the formulation that had BMR forage sorghum. All three formulations were comparable to each other.

“It shows the lesson that with some adjustments, it might be a good substitute if needed,” Bernard says.

Another study Bernard pointed to, this one done by Penn State, substituted 10% of the corn silage ration for early-lactation cows with BMR dwarf pearl millet. The pearl millet was harvested at the flag leaf stage, about a foot tall.

Results showed milk production taking a little bit of a hit, but on an energy-corrected basis, milk yield was the same. Again, with some tinkering, warm-season annuals can work in a system, but it takes some research on a farmer’s part.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like