May 14, 2019

Are you confident that all the nitrogen from the anhydrous ammonia you applied last fall is available this spring? Did you apply manure on a field as a source of nitrogen? The only way to know if that nitrogen is available for your corn crop is to test the soil for both nitrate and ammonium.

More farmers are sampling their soil and having it tested for nitrate content. If they apply anhydrous ammonia, they should have it tested for ammonium, too, says Jim Friedericks, director of outreach and education for AgSource Laboratories, based at Ellsworth in central Iowa.

“When nitrogen is added to the soil as fertilizer or manure, it is not stable,” he notes. “The longer the nutrient is in the soil before crop uptake the greater the risk of losing some of the nitrogen. Hopefully, most of the N will be captured by the crop roots, but some will be lost by natural processes. Rather than guessing what is going on, it is better to sample and test the soil, so you can manage it.”

Value of nitrogen testing

Plants absorb nitrogen from the soil as either nitrate or ammonium. Nitrogen can be added as fertilizer, including forms such as ammonium, nitrate or urea. Or it can be added as more complex organic forms like manure or in crop residues.

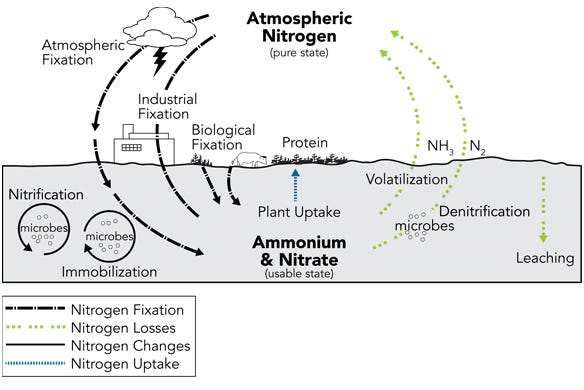

The nitrogen in crop residues and in the organic portion of manure is bound up with cells and fiber, so it must go through a biological decomposition before it is released as ammonium in the soil. Then, as depicted in the nitrogen cycle chart below, ammonium and nitrate can be used by plants or other soil organisms, or it is lost through leaching and volatilization.

“The processes that impact nitrogen in the soil are a challenge to work with, especially in the spring when soil temperature and moisture levels change so quickly,” Friedericks says. As soil warms up, nitrates are formed from the ammonium in the soil. This conversion is faster when the soil is above 50 degrees F. But wet areas in a field will warm up more slowly, and excess moisture in the soil can either leach the nitrate, or the nitrate might be converted to gaseous nitrogen and be lost to the air if the soil remains waterlogged.

Incomplete measure can be costly

Just analyzing the soil for nitrate reflects the fact that ammonium typically converts to nitrate rapidly in warm soil. But if fertilizer was recently applied, or if a nitrification inhibitor was applied with the fertilizer, then considerable amounts of ammonium can be present even after planting. In that situation, a low nitrate test value indicates the incomplete conversion to the nitrate form, not a deficiency of nitrogen. Also, a soil with a pH of less than 5.5 can restrict the rate of this biological conversion.

Because soil organic matter is a source of nitrogen, and these conversions occur naturally in soil, there is typically a “background” concentration of both ammonium and nitrate even in an unfertilized soil. Those values are typically between 4 and 8 parts per million for both nitrate and ammonium.

The nitrogen cycle

Friedericks recalls a recent example of the usefulness of testing ammonium in the soil. “A grower applied manure last fall and sent soil samples to the lab in April. He called with questions because the soil test nitrate result showed only 7 pounds of nitrogen available in the field, and he was worried that he had lost all the nitrogen he had applied. When the ammonium was also tested by the lab, the soil had 150 pounds of N as ammonium, showing that the conversion process had not started in his field, and he could account for all the nitrogen he thought he had.”

Avoid expensive mistake

The moral of this short story is if you don’t test for both ammonium and nitrate, you may be getting an incomplete measurement — potentially causing an expensive mistake.

Here are a few ways to use laboratory analyses to measure nitrogen availability:

Add a nitrate and ammonium evaluation to standard soil test. The results reported by the add-on tests are limited because the tests only evaluate the top 6 to 8 inches of soil and won’t account for the downward movement of nitrates.

Secure a profile nitrogen sample from two depths. Collect the sample at a depth between 0 and 12 inches and between 12 to 24 inches to account for the mobile nitrate down to 2 feet. Adding an ammonium test to the top 12-inch sample can indicate nitrogen that is available but not yet in the nitrate form.

Collect soil sample for PSNT when corn is 6 inches. The pre-sidedress soil nitrate test is used to adjust the N application for the intense growth in the following weeks. The PSNT measures only the nitrate in the upper 12 inches of soil.

Apply some manure. PSNT recommendations are most accurate when the field has had manure applications. If only commercial fertilizer has been applied, the test can underestimate the amount of sidedress N required to sustain the crop.

Add ammonium test. Consider adding an ammonium test that better measures the amount of N available to the crop. The ammonium found in the soil can be reduced from the recommendation, keeping in mind that there is always some background ammonium in the soil.

AgSource Laboratories provides agricultural, turf and environmental laboratory analysis and information services, with facilities in Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Oregon. Learn more at agsourcelaboratories.com.

Source: Ag Source Laboratories is responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and its subsidiaries aren’t responsible for any content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like