April 18, 2017

Nitrogen on Corn in 2016: A First Look | The Bulletin: Pest Management and Crop Development Information for Illinois

By Emerson Nafziger, University of Illinois Extension

The 2016 cropping season was a good one in Illinois, with planting a little ahead of normal and good May moisture and temperatures to get the crop off to a good start. June was warm and, in most parts of Illinois, drier than normal; parts of western Illinois received less than an inch of rainfall for the month. Temperatures and rainfall returned to normal in July and August, though there was the usual variability from region to region, including much-above-normal rainfall in the southern end of the State.

With good May soil conditions, mineralization got off to a fast start, and the crop in most fields was dark green by the end of May and starting to grow rapidly. Without N loss conditions in June, N from both fertilizer and mineralization stayed in the rooting zone, and N availability to the crop was outstanding. Even no- or low-N strips stayed dark green in trials into the middle of June, much later than we normally see N deficiency developing.

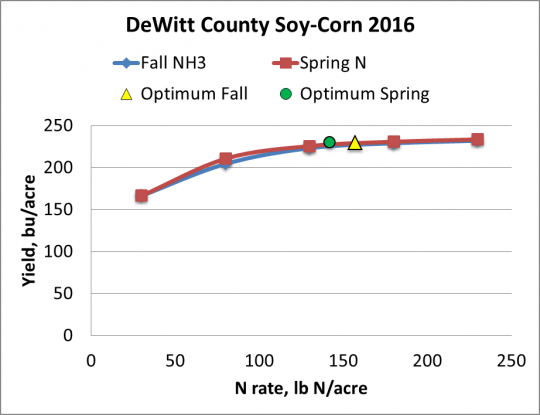

The retention of N in the soil and its availability to the crop carried through the season to diminish the need for fertilizer N. Figure 1 shows a response to N in an on-farm trial in DeWitt County, Illinois. Not only did about 150 lb. of N maximize yield at 230 bushels per acre, but it made almost no difference whether the N was applied in the fall or in the spring. We know from our N tracking that most of the N was in the nitrate form by the time crop uptake started in late May; we can see here that in the absence of N loss (wet) conditions, nitrate stays in the soil and is available for plant uptake just like ammonium.

Figure 1. N responses from fall- and spring-applied anhydrous ammonia in an on-farm trial in DeWitt County, Illinois in 2016. Optimum points are the N rate and yield at the point where the last addition of N provides just enough yield increase to pay for that N.

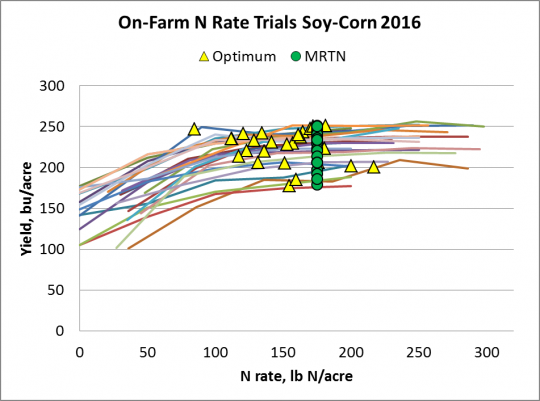

Dan Schaefer of IFCA coordinated dozens of on-farm trials similar to the one shown in Figure 1. Some had fall versus spring N timing comparisons, some had all early versus some early plus sidedress, and others just compared yields at different N rates. Figure 2 shows results from 26 trials conducted across central Illinois in 2016.

Figure 2. N responses from 26 N rate trials in corn following soybean in central Illinois, 2016. Each line connects the data points from one trial, and the optimum points (triangles) are calculated from curves (not shown) fitted to the data. The MRTN points are calculated as the yield at 175 lb N/acre, which is the MRTN (optimum N rate) calculated for central Illinois corn following soybeans at a N to corn price ratio of 0.1 ($0.375/lb. of N and $3.75/bushel of corn.)

In 2015, high N loss conditions and damage from standing water resulted in high optimum N rates. In 2016 we found just the opposite: Figure 2 shows that relatively low rates of N were needed to maximize yield in nearly every case. Of the 26 trials, only five had an optimum N rate higher than the MRTN rate, and on average across trials, only 150 lb. of N was needed to produce an average yield at the optimum N rate of 225 bushels per acre. Some like to calculate “efficiency” of (fertilizer) N by dividing yield by N rate; here, we calculate a very high efficiency of 2/3rds of a lb. of N per bushel of yield, or 1.5 bushels per lb. of N used.

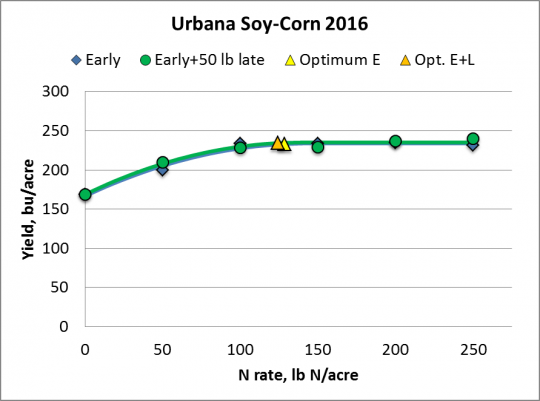

We ran a new study at a number of sites this year to compare the application of N rates at planting to keeping 50 lb. of N back and applying it dribbled next to the row at tasseling. Figure 3 shows the results of the corn following soybean trial at Urbana.

Figure 3. Response to N applied as UAN at planting (early) compared to applying all but 50 lb. of N at planting them dribbling the remaining 50 lb. next to the row at tasseling.

Nitrogen on Corn in 2016: A First Look | The Bulletin: Pest Management and Crop Development Information for Illinois

Responses to late-split timing of N at other sites were all similar to that in the trial shown in Figure 3. We had three corn following corn trials and four corn following soybean trials, and in none of them did keeping back 50 lb. of N to apply late provide a benefit to either yield or return to N; that is, late-split application did not pay the added application cost. This makes sense given the low N loss conditions in 2016. We would expect to see some loss and possible response to late supplemental N following a wet June, though we did not see much response to a single treatment (150 lb. N early versus 100 early and 50 at tasseling) in 2015.

We’re seeing N “at its best” in 2016; it was there in abundance when the crop needed it, and adding the supply of N from soil organic matter meant that the crop needed less fertilizer N than it has typically needed, even at high yield levels. We can’t depend on this to happen in 2017, but we see clearly that the common idea that “high yields require high N rates” often does not hold true. There is certainly no need to raise rates for next year, and fields that received more N than was needed in 2016 (according to N response curves that is probably most fields) might have added to the pool of soil N that can be tapped by the 2017 crop, whether that’s corn or soybean. Keep in mind, though, that what we saw in 2016 was mostly a response to the (June) weather and crop off to a good start; we will need to watch how things develop in the spring of 2017 to know if we’ll have a repeat.

Originally posted by the University of Illinois Extension.

You May Also Like