Think differentYields from N forms are very similar, studies show, although anhydrous ammonia is the most stable form. Apply your chosen form as close to plant uptake as your operation allows.Preplant spring anhydrous ammonia is the best bet for reducing N loss.Manure showed the highest economic gain over any other N form.Sidedressing as a primary fertilizer source has big advantages in wet years when it’s questionable whether a crop will be planted.

August 26, 2013

Your choice of nitrogen (N) comes down to when you apply, your equipment, handling preferences, availability and costs. And the weather wild card often determines whether you’re happy with your choice in any given year.

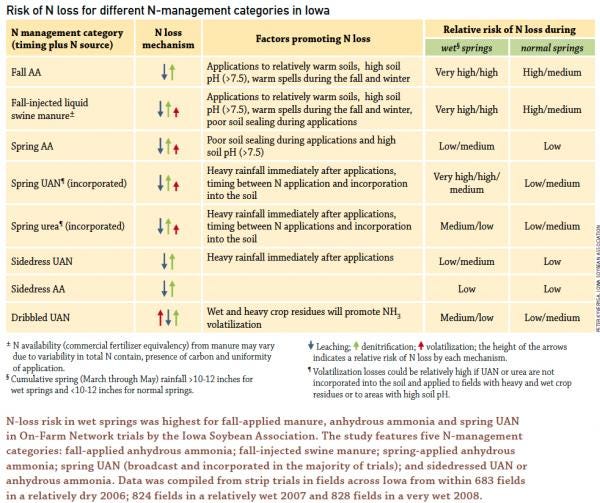

Your N-loss risk hinges on timing, source and rainfall, says Peter Kyveryga, senior research associate with the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA) On-Farm Network. Anhydrous ammonia is the most stable form, since it takes longer to convert to nitrate, he says. “Some sources, like liquid N, already contain nitrate, which can be lost quickly in heavy rains after application. But extended wet soil conditions hasten N loss in any form. The closer you can apply N to the time of maximum corn uptake, the better.”

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to CSD Extra and get the latest news right to your inbox!

(Click the image for a larger version.)

Spring ammonia wins ISA trials

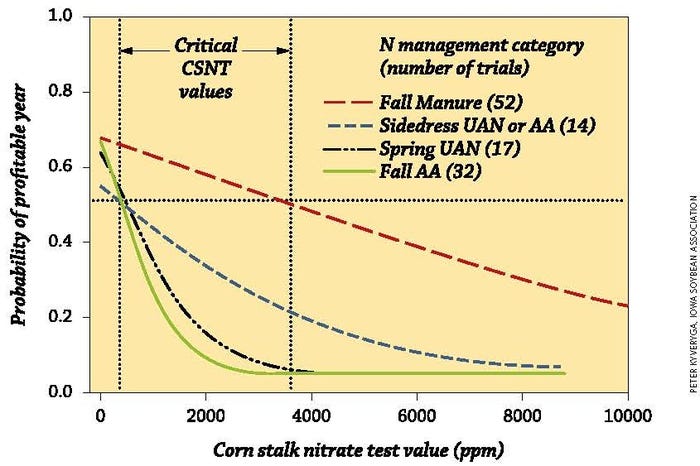

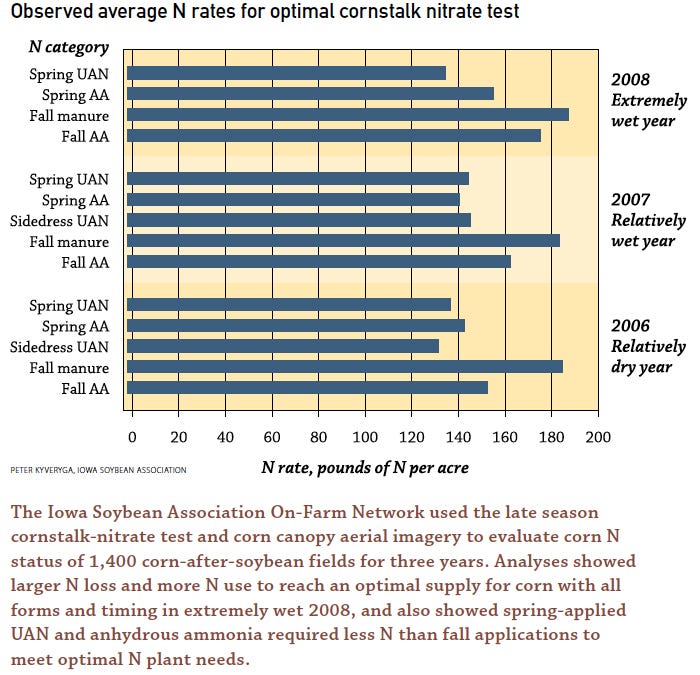

Preplant spring anhydrous ammonia is the best bet for reducing N loss, says Kyveryga of his on-farm trials. The ISA On-Farm Network used late-season aerial imagery and cornstalk nitrate testing to estimate the size of N-deficient areas within 683 fields in a relatively dry 2006; 824 fields in a relatively wet 2007 and 828 fields in a very wet 2008.

More N from fall manure was required to reach optimal N values in cornstalk tests than from any other N source or timing in each year.

Fall-applied anhydrous ammonia required the second-highest amount of N for optimal cornstalk test status, while spring and sidedress applications consistently required the lowest amount of N. In the extremely wet 2008, most of the stalk samples from side-dressed UAN were N-deficient. But, sidedressing UAN also saved on total N needed to reach optimal cornstalk N values.

There was a higher probability for economic gain from adding more N (achieve an extra 5 bushels an acre from adding 50 pounds of N to manure rates farmers usually use) on manured fields than for any other form. This surprised Kyveryga, even after four years of 125 strip trials that he analyzed from a profit perspective. That was despite the fact that manured fields already had slightly higher N rates applied than any of the other N forms.

UAN offers sidedress flexibility

Frank Moore, who strip-tills corn and drills soybeans on about 2,000 acres in Howard County, Iowa, likes the flexibility that comes with sidedressing nearly all his N. “It was especially important this year. It was so wet so late in Howard and Mitchell counties that some people didn’t get any crop planted; I got only half the corn and soybeans planted that I intended,” Moore says.

“Anyone who had fall-applied N, or early preplant applied, lost a lot of that N with the heavy rains. And if they didn’t get a crop planted, they didn’t get any return from that expense of probably $60 an acre. In my case, when I couldn’t get the corn crop planted and took preventive planting through Federal crop insurance, I didn’t have the lost expense of unused fertilizer.”

Moore likes liquid N. He’s sidedressed nearly all his N fertilizer as liquid 28% UAN for nearly 10 years. “It may cost a little more, but I like the safety of using it compared to anhydrous, and I can drive faster to cover more acres,” he says. “Anhydrous knives aren’t compatible with the rocks we encounter in this area, either. Each form has its advantages, but I’m set up for liquid N with my equipment and it seems to be working for me.”

Moore’s Conservation Stewardship Program incentives and contract lock him into using no more than 30 pounds per acre of N on corn ground before planting. He broadcasts about 30 pounds of liquid N that helps act as a burn-down with his herbicide right after planting but before emergence. Then he uses the online Adapt-N program to determine how much N he needs to sidedress. That can be quite a bit. According to Ohio State University, corn N uptake can range from 4 to 8 pounds per day per acre between the V8 and tasseling.

Sidedress in eastern Corn Belt

Up to one-fourth of Indiana’s N goes on in the fall as anhydrous ammonia, almost all of it with an inhibitor, estimates Purdue’s Jim Camberato, fertility specialist.

“The earlier you apply, the more efficient anhydrous ammonia is compared to other forms, because it is the slowest form to convert to nitrate,” he adds. “So that’s the form to use in the fall or with early spring applications, especially in a wet spring or fall. But we can lose 15% of that to the environment, even with an inhibitor, research shows. So the less N you apply in the fall, the better. We get a lot more rain in the fall and winter, so you see a lot more sidedressing here—I would say at least 50% of the corn is sidedressed in our area and maybe more in Ohio.”

Over time, there’s little difference in using liquid N and anhydrous ammonia at sidedress, Camberato says. “Because sidedressing is a later application and the soil is drier at that time, you don’t get much loss with either form. But in a wet year, you could lose more with liquid N because about one-fourth of it is in nitrate form and is susceptible to loss immediately. It’s an even bigger issue with preplant because the time is longer before plant uptake.”

Banding urea instead of broadcasting either the granular or liquid form will slow conversion to nitrate.

In Ohio, UAN is the predominant form of N used, “partly because of safety issues,” says Extension Agronomy Field Specialist Greg LaBarge of Marion, Ohio, “and partly because that’s the form providers handle.” There was no corn yield difference between UAN and ammonia in a six-year study that he and OSU Fertility Specialist Robert Mullen conducted from 1998 to 2004.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like