September 15, 2016

Think Different

John Peterson had just applied a dry nitrogen fertilizer for his corn crop, anticipating a nice quarter-inch rain to work it into the soil.

Unfortunately that rain turned into a 2.5 inch event, and despite his no-till soils’ high water-holding capacity, a half-inch of water per acre ran off his fields, carrying away ten pounds of N per acre.

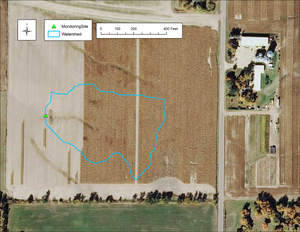

He learned this data from the monitoring station installed at the edge of his field by Minnesota Discovery Farms.

Peterson is changing over to a liquid N product and keeping a closer weather eye, to prevent a repeat of this mishap.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Farmers in Minnesota and Wisconsin know that April through June is the most dangerous period for nutrient runoff.

How do they know this?

It’s not from predicted data, models or computer simulations. The farmers know this from actual data, captured by field-edge monitoring on real, commercial farm operations. Discovery Farms – a farmer-led research project model is now well established in Minnesota and Wisconsin. So far, Discovery Farms Minnesota has a dozen farmer cooperators and Discovery Farms Wisconsin has about 40. The aim is to discover the true impact of farm management on water quality, including finding solutions that really work.

John Peterson, who manages Spring Creek Farm in North Branch, Minnesota, produces no-tills soybeans and had no-tilled his corn until this year, when he decided to switch to modified strip-till for his corn. Discovery Farms Minnesota has shown him that he has high-normal P losses and periods of high runoff despite very limited tillage.

The data from his runoff shows that 74 percent of it takes place in March and April, but the danger continues through the beginning of June. He knows that, on average, 11 percent of the precipitation runs off his land and all this happens on about a dozen days out of the whole year.

Knowing the exact mechanics of runoff and nutrient loss have helped him decide to try a different, liquid N product. Also, he now plans to band P&K at a six-inch depth to hold on to those nutrients.

No-till stops most runoff

Limited tillage does provide impressive water-holding capacity. In a location that receives 30 inches of annual precipitation on Peterson’s farm, less than four inches leaves as runoff.

At a field day at Spring Creek Farm, Warren Formo described John Peterson as a farmer who displays endless curiosity and creativity, always seeking out better ways to manage the corn and soybeans operation he farms with his wife Jewell, sons Nate and Nic and daughter Natasha.

“If the piece of equipment they need doesn’t exist, the Petersons build it,” says Formo, who is director of Minnesota Agricultural Water Resources Center, a farmer-supported organization that provides funding for Discovery Farms Minnesota through grants from Corn, Soybean and Turkey commodity groups.

Data fine-tunes split N applications

Dennis Mitchell, who farms in New Richmond, Wisc., says his dad abandoned fall commercial N application decades ago. He is using the Discovery Farms Wisconsin data to fine-tune the timing of his split application in the spring.

“The main thing we wanted was to see what kind of runoff we had,” says Mitchell. “We wanted to see if our tillage practices were doing what they are supposed to do, and then to go from there, to learn from it. We could see if we make changes what effect the changes make.”

In addition to learning about snowmelt runoff, this monitoring has shown him that he has a second interval of high runoff probability in June. His practice has been a pre-plant urea application and then a 10-gallon sidedress with 28% in June, for a total N of 180 to 200 lbs. per acre, especially on the irrigated fields. In addition to a spring pre-plant and a pop-up, Mitchell swaps out 90 pounds of commercial N for three tons of turkey manure per acre on some fields, especially corn-on-corn or in fields testing low for phosphorous.

In order to reduce May-June risk of nitrogen loss from runoff and leaching, Mitchell has reduced the pre-plant application, and increased the mid-June sidedress application. But increasing from 10 to 25 gallons/acre in some cases means refilling the tanks more often, which expands the application time.

“We got it done this year, but finishing all the corn is the challenge,” says Mitchell, who works 3,500 acres of corn and soybeans with his two brothers, Terry and Steve, and his son Kyle. “The sidedress applicator has a three-foot clearance, so when the corn gets to that point, we’re done.”

University N recommendations need improvement

Farmers know that nitrogen is a major yield-limiting nutrient for corn, and want to achieve greater efficiency.

To that end, Discovery Farms Wisconsin believes that even university N recommendation are not specific enough, says Matt Ruark, a University of Wisconsin soils scientist and faculty advisor to Discovery Farms. Ruark says we should look at crop nitrogen needs at the watershed level, or better yet, have individual farmers continually assess each field to discover the right rate and timing for their soils, landscape and type of operation.

Discovery Farms Wisconsin has done field-edge water quality monitoring with a few of their farmer cooperators for the past five to seven years. Last year, they began a three-year nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) study, working with 43 farmers. At each participating farm, crop consultants take soil nitrate tests before planting, midseason and after harvest. Corn tissue tests at silking/tasseling time determine how much N the plants have taken up. More than a hundred fields have been tested this year and last.

First year corn results saw a range from 0.89 to 2.0 bushels per pound of N. The majority of the farm operations—representing a diversity of watersheds across Wisconsin—fell in a midrange, yielding 1.21 to 1.66 bushels of corn for every pound of N applied.

“NUE work has been done in Iowa and Illinois, where growing conditions are a bit different from Wisconsin,” says Amber Radatz, co-director of Discovery Farms Wisconsin. “We use a lot more manure than they do. (70 percent of Wisconsin farms use manure for fertilizer). So we want to establish numbers for a typical Wisconsin farmer, and help them improve as needed. The rate that nutrients in manure become plant available is influenced by climate and soil, so region-specific study is essential.

“(In some watersheds) there was a lot of residual nitrate in the soils,” says Ruark. “There are some opportunities for farmers to credit some nitrogen, but that is going to vary from year to year. N management is evolving. This is just another way for farmers to learn about what they are doing and pinpoint where they can make improvements. Our ideal goal would be that the farmers would continue self-assessments over time, as a useful tool for them to see if they are maintaining or dropping in efficiency.”

Check soil with a zero N plot

Some fields hold onto nutrients better than others, and offer a nutrient foundation that benefits the crop. The only real way to determine background nutrition potential of your soil is to raise corn with no added nitrogen.

“Our goal is to see how well soil is able to mineralize nitrogen and keep it there,” says Todd Prill, the Discovery Farms Wisconsin technical adviser for Dry Run Creek watershed, where Mitchells farm is located.

In three zero applied-N plots, researchers took three in-season soil nitrate samples and a plant tissue uptake sample at tasseling/silking time.

“The test showed a tendency to lower N values more than we see in Mitchells’ traditional N management,” says Prill. “We measured 170 bushels (on the zero N plot), compared to the 220 bushels in the normal management areas.”

Mitchell adds, “We did notice that the stalks in the plot were broken, like the plants had cannibalized themselves to reach the yield they did, so we wouldn’t ever want to zero out the nitrogen. But we might be able to reduce it slightly and not notice a difference.”

These zero N plots can be used in different field areas to determine where less N could be used. Plus this data gives farmers an idea of efficiency of applied N versus what’s already in the soil.

--------------

Tillage tips to cut runoff

For John Peterson, it’s all in the ‘fingers.’ He has modified his no-till planter with his own design of two ‘finger’- or spade-style closing wheels for each row, toed out from one another.

The two wheels break the small ribbons of compacted soil that form in the process of making the seed trench. These closing wheels make a ‘rooster tail of dirt’ fly up and settle loosely over the seeds.

“I don’t want any compressed soil over my seed,” Peterson is adamant. “That little sprout can push through that loose soil so easily it will emerge a day sooner compared to coming up through compressed soil.”

And it saves soil from runoff. It may be counter-intuitive, but Peterson has found that this looser, feathered soil stays in place better, when it rains immediately after planting.

“If the seeds haven’t sprouted yet, it’s not uncommon with a heavy rain event—a fast two- or three-inch rain—that on some of the side hills it can actually wash away compressed dirt that you have placed over the seed and just wash it right down hill and take the seeds with it sometimes too. If you leave the soil loose it absorbs a lot of water before it is going to start washing. But if you have compacted the soil over the seed, that soil is going to start running down as soon as it starts raining and it will start washing away immediately.”

Dennis Mitchell avoids deep tillage in the spring, working the soil primarily with a field cultivator, mounted with points (rather than shovel tips), turning up only the top two to three inches.

“We like the points because you don’t turn up so much soil,” says Mitchell. “You are just breaking ground lose, drying it out a little bit. Typically that’s the biggest problem around here, it’s too wet and cold at planting time.”

This limited tillage seems just right—they averaged 215 bushels across both irrigated and dryland acres last year. And he likes the fuel savings of this lower energy approach.

You May Also Like