May 3, 2022

We’ve been through ups and downs before. Farms survived then and they will now, but not without some changes.

Remember the old farmer saying, “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results is the definition of insanity.”

When it comes to your dairy farm, a key step is to maximize the amount of milk produced using the least expensive feeds. In short, you want more money for your efforts, which is not the same as more milk.

This is doubly critical for farms who have been told to limit their production by their processor. Some are reducing the number of cows to meet those milk production limits.

Higher forage increases components, so you get paid more for the milk. For the majority of dairy farmers here and in Canada, the least expensive source of energy and protein are the forages you produce.

By feeding better-quality forage, you can increase the total amount of forage your cows will eat. These are nutrients you don’t have to buy into the farm.

But increasing forage should be done one small step at a time. At each step, the ration needs to be rebalanced. This can be done while producing the same amount, or even more, milk without sacrificing body condition.

What is a high-forage diet?

We used to say that 65% forage was the standard. Now, there are numerous farms where 70% forage is the standard, and some farms have gone even higher. This is done without giving up milk or ruining body condition score.

Feeding a cow like a cow (forage) is an old idea that is critical today. You need good-quality forage, you need enough forage, and you need a nutritionist who is on board and supports your goals.

You will not get there overnight, but making small changes will increase forage over time.

Our work in the 1990s, as documented by the Cornell Dairy Farm Business Summary and by Larry Chase of Cornell — “Benefits of high-forage diets on 14 case farms,” 2012 — found that farms with high-forage diets got greater components, had improved herd health, had less metabolic disorders and acidosis, saw a 30% increase in income over feed costs, and a decrease in open accounts.

Quality over quantity

To achieve this, you need greater than 60% neutral detergent fiber (NDF) digestibility forage. This means the focus on forage quality will be critical.

Quality is driven hugely by the stage at harvest. The first crop ready to harvest in spring is the winter forage — triticale or rye. Our research over 20 years has found that the flag leaf (stage 9) is the optimum balance between yield and quality. Rye is usually the first to flag leaf, but newer triticale varieties are just as early.

The other factor to consider is when you planted it last fall. Each week of delayed planting usually adds two to three days to when the crop is ready to harvest. Because quality is so critical to high-forage feeding, it is better to err on the side of too early than too late for winter forages.

If you are at stage 8 (the last leaf rolled) and are facing a week of warm, rainy weather, we suggest harvesting before the rain. You will lose 25% to 35% of the yield, but will maintain the very high digestibility and probably have higher protein as the nitrogen is spread over less dry matter.

If weather delays harvest and there are colder temperatures, the quality will often hold through the boot stage, so don’t give up. Ideally, you will have nice weather when the last flag leaf is all the way out (stage 9).

For intensively managed grass and alfalfa grass mixes, the grass is ready about a day or two after the winter triticale. Every analysis I have seen shows significant profit advantage to stopping corn planting and getting the first cutting in at peak quality.

A phenological predictor developed by John Winchell of Alltech is to look for a dandelion head that has turned all white in an all-grass field. When you see this, it is time to mow the straight grass fields.

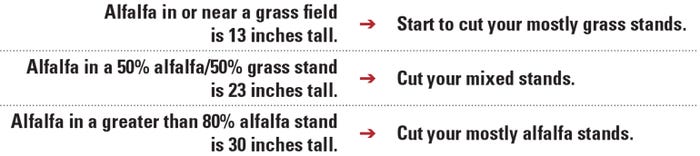

Your individual fields of alfalfa mix should determine when you should start harvesting, using your alfalfa as a predictor. The height of alfalfa can help you predict when you should cut. It simply involves using a ruler and the following table developed at Cornell:

A more precise system is to visit forages.org.

Jerry Cherney of Cornell developed this slick, accurate system. Click on the grass, alfalfa-grass or alfalfa estimator. For the latter two, insert the alfalfa height, percent grass, NDF target and the weather (normal, hot, cool), and it will tell you how many days until that field, under your conditions, is at peak quality for harvest.

Using the predictor system to determine what fields to harvest first allows you to harvest all fields at peak quality.

If the weather causes you to miss high-quality forage on a field, skip it and go on to the next quality field. The skipped field can be used for dry cows or heifers.

Don’t make the rest of the fields late because of the one you missed. You need high-quality forage from all fields. If you have fields that are in a low, warm, sheltered location, they will be ready earlier than the rest of the farm.

Fields with well-drained soil will have forage ahead of a poorly drained field. A north-facing slope will be further behind than a south- or southeast-facing slope. A clear alfalfa on a well-drained south-facing field could be ready before a grass field on a wet, north-facing slope.

Utilizing wide swath, same-day haylage will open more days for you to get your winter forage and your other haylage harvested. Not only will it give you more days to get the harvest in, but it will also increase the feed value by increasing digestible components for supporting milk and speeding fermentation to conserve more of the feed that gets fed to your animals.

Kilcer is a certified crop adviser in Rutledge, Tenn., formerly of Kinderhook, N.Y.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like