January 8, 2021

The USDA Farm Service Agency is rolling out a new round of Conservation Reserve Program sign-up in early 2021. The competitive general sign-up for CRP runs from Jan. 4 to Feb. 12, while the relatively new CRP Grasslands program holds its competitive sign-up from March 15 to April 23.

Of course, landowners also can enroll certain priority acres and practices at any time through the Continuous CRP program without facing competition for acceptance.

Over its 35-year existence, CRP has set aside millions of acres out of production into conservation uses, reducing soil erosion, improving wildlife habitat and vegetation, protecting water quality, and capturing carbon with permanent vegetative cover.

When CRP was originally included in the 1985 Farm Bill, it was valued by a coalition of agricultural groups and environmental groups as much for its role in taking cropland out of production at a time of excess supplies and low commodity prices as it was for its environmental benefits.

Since then, the program has transitioned more toward its environmental objectives with general enrollment selection based on environmental benefits — as well as the introduction of targeted enrollments through the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, Continuous CRP, CRP Grasslands program and other provisions.

Corn price relationship

However, CRP still effectively idles more than 20 million acres at present, taking land out of agricultural production, save for some managed haying and grazing. With more than $1.7 billion in rental payments this past year, CRP has provided substantial and steady income to landowners.

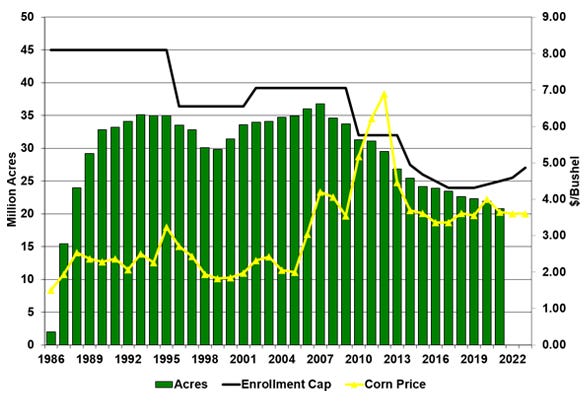

It is not a surprise that steady CRP income looks more attractive to producers when ag commodity prices are down. Looking at enrollment over time, it would seem that there is an inverse relationship between enrollment and commodity prices, as represented by the national marketing year average corn price.

The correlation is too weak and is likely lagged a bit to be a complete explanation, but the relationship surely matters, and the history of the program would suggest it as well.

CRP enrollment and corn prices over time.

As noted, CRP was created in the 1985 Farm Bill at a time of excess supplies and low commodity prices. Enrollment quickly grew to more than 30 million acres, but it started to fall in the late 1990s as initial contracts expired and prices briefly moved higher.

By the early 2000s, low prices and increased enrollments led to nearly 37 million acres in the program. Concerns at the time about the large number of acres set to expire in the 2007-10 period led to calls for contract extensions to avoid returning so many acres to production and the potential negative effect on prices.

In response, USDA rolled out the Reenrollment and Extension (REX) Program in 2006 to extend contracts. But just as the REX agreements were being approved, commodity prices improved, and there actually were calls for USDA to offer early-out provisions instead.

With higher commodity prices in the late 2000s and early 2010s, interest in CRP waned, and total enrollment started falling. Both the 2008 Farm Bill and 2014 Farm Bill chased the declining enrollment with a reduced maximum enrollment to capture the reduced spending and count it as budget savings toward the overall cost of each farm bill.

Changing enrollment cap

The enrollment cap was reduced from 39 million acres to 32 million acres under the 2008 Farm Bill, and to 24 million acres under the 2014 Farm Bill, limiting potential new enrollment in CRP even as lower prices would have made the program more attractive.

In the new, lower-price environment, the 2018 Farm Bill reversed course with an expanded cap, growing to 27.5 million acres by 2023. However, the expanded cap also was combined with a provision to reduce the maximum CRP rental rate to 85% to 90% of the average local cropland rental rate to help offset the budget cost of expanded enrollment.

With the rental rate reduction, along with some commodity price recovery in the past couple of years, total enrollment in CRP has continued to drop in spite of the larger cap.

The current general enrollment period will be a test of producers’ preferences for stable rental income under CRP versus crop production potential, and the prospects but uncertain staying power of current higher prices versus longer-term projections.

There could be additional opportunities for CRP acres in the future as well, with potential climate legislation or policy that rewards carbon sequestration, although current discussions suggest more attention to working lands programs such as the Conservation Stewardship Program than CRP.

Regardless, CRP has been and likely will continue to be one of the largest and most significant parts of the conservation program portfolio implemented by USDA.

Lubben is an Extension policy specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like