When a Hispanic couple drove into a Wisconsin farm couple’s yard looking for work eight years ago, it seemed like a perfect match.

“They were desperate for work, and we were desperate for help,” says the farmer, who had 10 positions to fill, mainly milking the farm’s 500 cows.

But what seemed like a dream turned into a nightmare with the latest federal government push to enforce immigration laws. The farmer in question wouldn’t share her name for this article, fearful that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents would show up at her milking parlor. The goal is to find legal help, but no Americans will do these jobs — and the cows won’t milk themselves. Meanwhile, her eight immigrant workers live in fear, too scared to drive to get groceries or go to their daughter’s high school choir concert.

“We plotted how they could drive without driving on state highways to calm their fears,” she says.

Is this any way to run a business? Yet, it’s a story similar to thousands of other farmers and their labor forces, now caught in the crosshairs of a broken system with no fix in sight.

Ag’s backbone

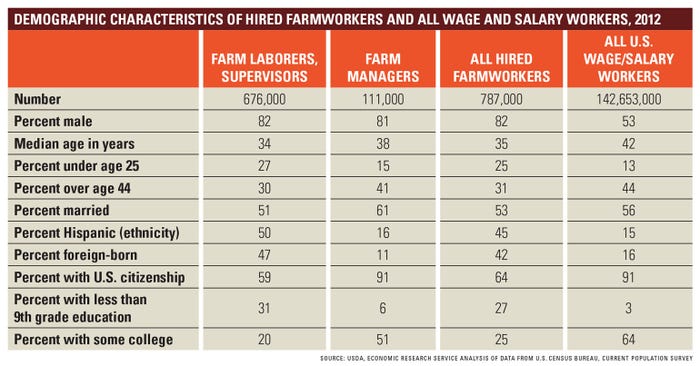

Many industries could not survive without migrant labor, and agriculture is certainly one of them. It’s estimated that 1.5 million to 2 million hired workers help fuel the U.S. farm economy. Unauthorized workers make up about 50% to 70% of them. U.S. agriculture would crumble in a mass exportation of undocumented workers.

That’s why alarms went off earlier this year when a U.S. Department of Homeland Security memorandum called for greater enforcement of rules that would facilitate the detection, apprehension, detention and removal of aliens who currently reside in the U.S.

Today, U.S. agriculture depends heavily on those falsely documented or undocumented workers. Regardless of the reform scenario studied, it is clear that a legal workforce would come at a price.

Politicians who cry, “They’re taking jobs away from Americans,” need a serious reality check. That faceless Wisconsin dairy farmer told Farm Futures she has tried — many times — to find legal labor. Ads in the local and regional papers or Craig’s List surfaced few candidates willing to put in the long grueling hours that come with a dairy. Foreign training programs offered a short-term legal solution, but people would leave or defect after working for the allowed year once operators had finally trained them.

Laurie Fischer, chief executive director of the American Dairy Coalition, says fear of the unknown is prevalent among dairy producer-members. They can’t build a business expansion plan simply because they don’t know who will milk the cows.

Dairy farms employed an estimated 150,418 workers in 2013. About 76,968 of those are immigrants. Immigrant labor accounts for 51% of all dairy labor, and dairies that employ immigrant labor produce 79% of the U.S. milk supply.

David Anderson, Extension economist at Texas A&M University, conducted a study on behalf of the National Milk Producers Federation released in 2015, which found that if 50% of the immigrant domestic labor disappeared, the U.S. dairy herd would be reduced by more than 1 million cows and milk prices would skyrocket by 45%. If 100% of immigrant labor goes away, retail milk prices would nearly double.

A 50% cut in dairy labor would cause a $16 billion loss to the U.S. economy.

The fruit and vegetable sectors face a similar dilemma. Without foreign workers on U.S. farms, American consumers would be buying much more imported food or have far fewer food choices. An immigration policy focused on closing the border would shift as much as 61% of U.S. fruit production to other countries and send jobs to nearby nations, such as Mexico, in part because wage costs would make U.S. foods less competitive, according to a 2014 study commissioned by the American Farm Bureau Federation.

In effect, such a policy would simply weaken the U.S. economy and make other countries richer.

Labor deficit

Finding labor has always been an uphill battle as farms consolidate and grow larger. The local labor community — aka U.S. citizens — may not want to work weekends or long hours during harvest season. That’s why the idea of mass deportation is so unsettling. Cutting the total unauthorized workforce by roughly half would push wages for undocumented and legal guest farm workers as much as 40% higher than they would have been otherwise over a 15-year period, according to a 2012 study by USDA.

Fieldworker wages averaged $12.59 an hour (based on October 2016 data). Wages for farmworkers were rising at a faster clip than non-farmworkers, based on U.S. Labor Department figures for the same month. However, the average wage for non-farmworkers was $25.90.

“Time and time again, my [dairy farmer] members reach out to domestic workers and have increased wages in order to secure domestic workers, without any luck. They just won’t milk the cows,” says Fischer.

“As this process continues to unfold, we will continue to lose our workforce,” she adds. “Not in my entire career have I witnessed so much fear from employers and owners of operations on where we’re going to get our workforce from.”

Kevin Merrill, a California vineyard manager, agrees. It’s rare for any “Anglo” to apply for jobs in his vineyards, he says. “Americans won’t do these jobs.”

Merrill recalls going to the local employment office to find people to work jobs in the wineries and for tree farming. “They came in, saw people up in olive trees, and they wouldn’t even get out of the car,” he recalls. “It’s hard, dirty work. It’s not a question of wages; they just won’t do it because they will get benefits and are able to live without these jobs, so they don’t have to.”

In many ways, the work ethic and family values of foreign Hispanics make them a good fit for agriculture.

“I had some Oaxacan people [from the state of Oaxaca in Mexico] work for us, and they got paid hourly and a bonus based on how much they picked,” Merrill recalls. “They would pick more than anyone else in the orchard. One night I was out late and I could hear olives going into the buckets at 7:30 that night; they stayed there that night and filled up all their bins. That’s how they got ahead of the others. They did it on their own because they wanted to make more money.”

Labor availability drives farming decisions. If a grower cannot depend on labor crews at harvest, those crops will not be planted here, despite good demand and profit potential.

“A lot of strawberry growers tell me the crop is ready and there’s no one there to pick it,” says Merrill. “There are times when stuff has to be harvested, and they don’t have the people to do it.

“We are operating at about 60% of the people we need right now. It’s almost like triage for us — where can we send people to stay ahead of it, and how does that translate in dollar costs, I’m not sure. But if that’s happening to us, it’s happening to others, too. Does quality suffer? It could be as high as $2,500 an acre in losses for us if you can’t get things done on time.”

Merrill is part of Mesa Vineyard Management Inc., a labor-contracting company focused, in part, on sustainable vineyard practices for winery owners on California’s Central Coast. The company’s trained vineyard management team includes hundreds of Hispanic workers. They are skilled workers who also get health insurance, a 401(k) savings plan and above-average industry wages.

“We try to do everything we can to maintain a workforce who will be with us a long time,” says Merrill. “What helps in the wine industry, to a certain extent, is we can mechanize — pruning, shoot-thinning by machine — so we’re going that way. But we can only do so much with the hills we have.”

Cannon Michael, who farms 12,000 acres of row crops and fruits and vegetables in California’s Central Valley, says he’s investing big bucks in technology to lower dependence on a human workforce.

Californian producers are being hit with multiple regulatory struggles, including limits on overtime hours and higher minimum-wage requirements.

Michael, who is a sixth-generation farmer, says he is exploring buying farmland in South America and other options just to stay in business. “It’s becoming increasingly difficult to see positive outcomes for us here,” he says.

California farmer Cannon Michael hires 50 hourly employees, plus hundreds of contract laborers for harvest. If given the required documentation by law and it looks legitimate, he’s not required to dig into employees’ backgrounds. “Legally we’re not supposed to challenge the information they’re providing.”

Increased enforcement

A current bill in Congress requests money for up to 10,000 additional enforcement officers. If that gets passed, and new agents start a crackdown, what would happen?

The Farm Bureau study found the hardest-hit domestic food sectors under an enforcement-only scenario would be fruit production, which would plummet by 30% to 61%, and vegetable production, which would decline by 15% to 31%. The study also said while many consider fruit and vegetable production the most labor-reliant sector, livestock production would fall by 13% to 27%.

Michael employs a core hourly group of about 50 immigrants, as well as additional contract harvest crews. He says this contract group of migrant workers is “poised for some disruption” with the ongoing ramp-up in enforcement. “We just don’t know what actions will be taken,” which, he says, puts him in a holding pattern on how to plan for the year ahead.

When and if stricter enforcement begins to impact U.S. food production, it’s a good bet such a scenario would amp up pressure to improve the immigration system.

“If it does translate into crop losses or shortages, we will be making that known and using those messages in an effort to move agricultural labor reform ahead,” says Kristi Boswell, AFBF director of congressional relations.

Getting legal

It’s hard to say just how many agricultural workers are considered undocumented. A 2009 Pew Hispanic Center study says it could be about a quarter of the U.S. farm workforce, or more than 300,000 people. Other studies suggest the number may be more than 1 million and as much as 70% of all workers.

The Texas A&M study asked producers how confident they were in the documentation workers provided them.

About 38.9% of the farmers said their confidence in such paperwork was low, and 32% had only a medium level of confidence.

At the time of the study in 2013, a majority of dairy farmers had a relatively high level of concern with respect to actions, such as raids or employee audits. Anderson suspects those concerns are more elevated now, but employers have no way to verify the documentation or ability to challenge what’s been given to them.

Michael says legally, as an employer, he’s not supposed to challenge information a potential employee provides him. “The people we hire have the required documentation by law. If they give us a Social Security card and if everything looks legitimate, we’re not required to dig into their backgrounds,” he shares.

Finding solutions

The current H2A temporary worker visas don’t meet the growing yearly worker needs of those in many agricultural industries.

Salinas, Calif., farmer Brian Antle says H2A on its best day is bad and on its worst day is terrible. “The inspections, the audits — we make it work, but it’s a giant bureaucratic headache,” he says. “It’s a cumbersome system we should look to fix, or go back to the old system where we had six-month work visas where people could come over and go back.”

Lynn Jacquez, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who’s held various roles over the years in reforming immigration laws, says the focus should be on using technology as labor saving not labor replacing. “Until we come up with a hybrid strawberry that doesn’t bruise when we pick it or lettuce that can cut itself, we need to focus on a more efficient labor allocation system [and] make it more year around for people to remain here and available. We need a multifaceted system.”

The anonymous Wisconsin dairy producer believes a solution to the immigration problem begins with acknowledging that certain industries have specific labor needs. “There’s an opportunity to identify industries in jeopardy of hurting our economy because of a labor shortage,” she says. Work visas can then be provided for them to stay in those industries.

Past experience shows that if given a way out, undocumented workers will quickly leave agriculture. The share of undocumented workers in the hired farm labor force dropped to 14% over 1989-91 immediately after the last round of reform, but rose back to pre-1986 levels (37%) by 1992-94, to 47% by 1995-97, and to 50% by 1998-2000 as farm employers had to replace exiting undocumented workers (legalized by the 1986 legislation) with new undocumented workers.

Some work within the dairy industry has pushed for a state-based visa program. That would allow Congress to sanction states to make their own decisions, and if they choose, permit a guest worker visa program run by individual state’s governments, based on the economic necessities of each individual state.

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has shown support for a new merit-based immigration system limited to people who can support themselves, saying it would raise U.S. wages and boost the economy.

Despite differences in Congress, many members want to fix what they call the “future flow” — systems or mechanisms to determine, regulate or control the future level of immigration going forward. Because there is an H2A program already, they don’t have to justify to their constituents a whole different type of worker visa program. Having something already in place, even if it doesn’t work, is a good thing; it just needs to be fixed for modern times, says Jacquez.

Window for reform

“There’s an underlying concern about the stability of the ag workforce, and that puts incredible pressure on the existing program we have — that without any changes it can’t meet ag’s needs,” says Jacquez. “We’re hoping this pressure will break the political logjam.”

In his initial days of office, Trump has put much of his focus on enforcing immigration laws, particularly removing violent criminals who are here illegally. In his speech before the joint session of Congress at the end of February, he spoke somewhat positively for the first time about the next steps in fixing immigration.

“I believe that real and positive immigration reform is possible, as long as we focus on the following goals: to improve jobs and wages for Americans, to strengthen our nation’s security, and to restore respect for our laws,” Trump told members of Congress. “If we are guided by the well-being of American citizens, then I believe Republicans and Democrats can work together to achieve an outcome that has eluded our country for decades.”

Boswell expressed optimism that the change in tone may help advance progress on Capitol Hill. She’s hoping some solid ideas will surface in late spring and early summer.

“Although it is a small step, it is positive recognition that this issue deserves more and immigration enforcement alone is not the solution,” she concludes. “I hope the White House taking these proactive approaches can open the logjam Congress has had addressing immigration.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like