May 12, 2014

In 2013, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) captured the limelight – and fueled the imagination for big strides ahead for real-time crop imagery.

In 2014, satellites may steal some of that UAV thunder if promises to deliver actionable images every week on every crop acre across the America’s heartland come to fruition.

With little fanfare, GEOSYS, the French-based satellite imagery company bought by Land O’Lakes in late 2013, began delivering weekly satellite crop images to U.S. farmers through WinField-affiliated ag retailers in April.

Satshot, another major satellite imagery provider, says it will begin providing weekly crop images beginning in 2015. For 2014, it has increased the frequency of its 5-meter resolution crop images to every three weeks, up from every four weeks in 2013.

Meanwhile, UAVs could begin delivering real-time anytime crop images for the 2016 crop season – assuming federal regulators hold to their fall 2015 schedule for releasing regulations governing commercial UAVs – or recent legal challenges to FAA regulations don’t speed up the timetable.

When combined with crop imagery from manned aircraft and ground-based sensor systems like Trimble’s GreenSeeker and Ag Leader’s OptRx, U.S. crop producers will have a wealth of imagery sources to help improve management of their crops.

The one-week difference

Until this year, the two satellite imagery companies – which procure images captured by a range of government and commercial satellites – promised to deliver useable crop images every three or four weeks. If image-shooting conditions were good, images might arrive every couple of weeks.

Even in a best-case scenario, images weren’t frequent enough to build an in-season scouting and crop management program around them, says Kevin Price, who recently retired from Kansas State University (KSU) after a 30-plus year career studying remote imaging.

“The problem with satellite imagery until now is we have only been able to get four images in a year,” says Price, who joined RoboFlight Systems, a geo-referenced aerial data analysis company, after leaving KSU. “You just haven’t had enough temporal resolution, or frequency.”

Weekly image frequency will be a game-changer. “Getting images once a week should be plenty often enough for use as in-season decision aid,” says Price. Ultimately, he expects imagery from satellites and UAVs to “work hand in hand” to provide raw data that will help farmers “react to crop stress in a timely manner to protect yield or reduce inputs.”

Assuming satellite providers can deliver images every week during the growing season, some of the top uses might include early monitoring of crop stands, weed pressure and nitrogen losses, says Bob Gunzenhauser, technical applications manager for DuPont Pioneer’s Next Generation Services Group.

Even with more potential uses of images with increased frequency, proof that in-season crop imagery will pay for itself will be critical to its success, he says. “One of the problems [to date] is that there hasn’t been a way to take imagery and make solid use of it,” adds Gunzenhauser, who was involved in a pilot satellite imagery program offered to growers in 2013. “The black box on turning this into value hasn’t been invented yet.”

Given the fast-changing imagery world, Pioneer hasn’t decided what imagery resources it will offer customers of its new Encirca Services platform in 2014. “We are still assessing various technologies, including satellite, aerial and UAV systems,” says Gunzenhauser. “We don’t want to just provide a pretty picture. We want to provide guidance based on local knowledge to help solve challenges.”

GEOSYS ups the ante

GEOSYS, which says it is the largest purchaser and processor of agricultural satellite imagery in the world, began offering services to the U.S. market through WinField in 2011. That’s when the two companies partnered to roll out new variable-rate prescription capabilities in Winfield’s R7 Tool, which are based on multiple zone performance maps derived from10 years of satellite data.

“The most efficient way to build a variable rate fertility plan is from building yield goals in each field zone, which are defined with what has happened in those zones in the past,” says Damien Lepoutre, GEOSYS president and founder. “We were able to do that based NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) data derived from more than 10 years of archived images.”

Taking on the next challenge – using satellite imagery to protect yield potential during the growing season – dramatically ups the ante because of the need for more image frequency, says Lepoutre.

“The problem in the U.S. is that it is so huge that it is impossible to go over the land mass every day capturing high-resolution satellite images,” says Lepoutre. Delivering one clear image per week requires several satellite passes each week to compensate for cloud cover, which makes images unusable. The company has successfully used that strategy for about a decade in Europe, where satellite imagery is used to drive multiple in-season variable-rate nitrogen applications in wheat.

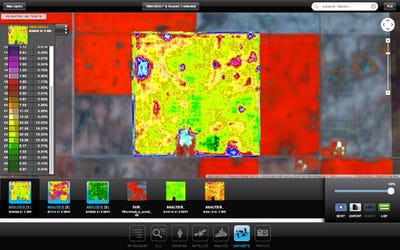

Near-infrared images of farm fields could be as commonplace as yield maps as imagery from satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) becomes widely available. Image courtesy Satshot

“We are confident that we will be able to provide a clear image every week, or five per month,” he says. To accomplish that, GEOSYS is procuring imagery from four satellite providers offering imagery at resolutions ranging from 5 to 30 meters. That’s up from two providers in 2013, when GEOSYS delivered a minimum of three clear images, and as many as a dozen, from April through August for every field across the Corn Belt.

“Five clear images a month is enough to be considered a crop scouting tool and a part of your decision-making process,” Lepoutre says. “That means any time a WinField agronomist goes to a customer’s field, he has the latest image and knows what to look for.”

In addition to the weekly high-resolution satellite image, GEOSYS is acquiring daily imagery at a 250-meter resolution. When used in conjunction with a 14-year database of similar images, agronomists will have a quick progress report of every field in their service area. “You can benchmark whether a field is behaving correctly every day or so, then you use the weekly 5- to 30-meter satellite image to analyze what is happening,” he says.

In 2014, GEOSYS satellite imagery will be available only through WinField affiliates. “It is critical that the grower gets the value from the image, which WinField has the skills to provide,” says Lepoutre. “Just having a nice image is not worth a high price unless you can have a positive affect the bottom line.”

WinField’s suggested retail price for full-service in-season crop imagery services, which includes agronomy support, field scouting to ground truth imagery and variable rate application maps, is $7/acre. For information, visit winfield.com.

Satshot rides new satellite wave

Satshot’s 2015 weekly satellite imagery service will be built around the launch of more than 100 new-generation satellites scheduled over the next year by Planet Labs, a Silicon Valley newcomer to the satellite industry. The new satellites – each about the size of a thermos bottle – will be able to capture images of every spot on the earth every day, according to Planet Labs.

“Once these satellites are launched, we might amass 30, 40, 50 images of a field every season,” says Lanny Faleide, president of Agri ImaGIS Technologies, which operates Satshot. “You start putting those images together in an animation and you might really start seeing something. The additional frequency will allow us to use more analysis tools. We will shift from being reactive to proactive in how we use satellite imagery.”

The Planet Labs satellites – which are minuscule compared to traditional multi-ton satellites – will capture images at a 3 to 5 meter resolution. The first 28-satellite “flock” of “dove” mini-satellites was launched from the International Space Station in January. The next 100, which Plant Labs says is the largest constellation of satellites in world history, will be launched in large groups from rockets over the next year.

As images are available with greater frequency, Faleide expects use of satellite imagery to grow “exponentially.” In addition to farmer demand, growth will be spurred in part by increased use from input suppliers, as well as machinery companies, which are working to enable tractor monitors to access satellite imagery, he adds.

For 2014, Satshot is offering 5-meter resolution imagery every three weeks, relying primarily on five identical RapidEye satellites, which were launched in 2008. Satshot is the primary distributor of RapidEye imagery in North America.

“Five-meter resolution has become the sweet spot for agricultural imagery,” says Faleide. “You can see so many more details compared to 30-meter images from Landsat and other satellites.”

Unlike GEOSYS’s ag retail distribution model, Satshot sells imagery to all comers. Images are available on-line. The Satshot web site provides an imagery database, analysis tools and a smartphone-based alert system that lets users know when a new image is available.

For 2014 images, the company is charging 50 cents/acre/image date for 5 meter-resolution images, including access to all on-line tools. Satellite images at the 30-meter resolution are free. For information, visit satshot.com.

Multi-layered future

When asked what technology will be the best source of crop imagery in the future, industry experts say the answer could be “all of the above.”

“A weekly satellite image will point out questionable areas of a field that require more checking,” says Lanny Faleide, president of Agri ImaGIS Technologies, which operates the Satshot remote sensing and imagery service. “The UAV can be configured to take a closer look at those areas at very high resolution. Now I can see the specks on the leaves or the insects that the satellite image hinted at.”

“With imagery from a satellite, plus a UAV or a ground rig, you will be able to pick the resolution you need and the time you need it,” says Mike Martinez, Trimble marketing manager for Connected Farm. “These systems will be synergistic.”

Satellites have the advantage of covering broad areas quickly at resolutions that capture general performance differences across a field. UAVs and manned airplanes offer a closer view of crop conditions, but cover a more limited number of acres in a day, notes Martinez.

Trimble’s new fixed-wing unmanned aerial system (UAS), the UX5, will be able to cover more than 500 acres in a 50-minute flight at a 2-inch resolution, which is recommended for infrared images that generate a high-resolution Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) crop vigor map. At a 1-inch resolution needed for early crop stand counts or capturing elevations used in drainage system planning, the UAS would cover nearly 200 acres in the same time frame.

There also can be synergies between imagery from satellites and UAVs and ground-based sensor systems like Trimble’s GreenSeeker and Ag Leader’s OptRx systems. But in many cases farmers who invest in ground rigs won’t have a need for aerial images to drive variable-rate nitrogen applications, says Chad Fick, Ag Leader product specialist.

“Each of these technologies has their advantages and disadvantages, but with a ground-based system like OptRx, you buy it once and your cost is fixed compared to buying images every year,” says Fick. “And we don’t have to worry about cloud cover like all the aerial systems do.”

UAV sensor imagery options

Near-infrared (NIR) imagery used to create Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) crop vigor maps is likely to be the mainstay of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), just as it is in satellite imagery.

But other sensors, including those that precisely measure heat and plant height differences may provide unique opportunities that aren’t possible with satellites.

NDVI maps, which measure crop biomass, provide a window on crop performance as measured by nature’s most perfected environmental sensor – the crop itself. Depending on the time of year, NDVI maps can provide a reading of the crop’s nutrient status, the effects of insect and disease pressure, eventual yield and more.

“There is nothing better than the plant at integrating all the variables affecting growth,” says Bruno Basso, an associate professor at Michigan State University, who is testing a UAV with NIR, thermal and laser-based (lidar) distance sensors under a program funded by Michigan corn growers.

Michigan State University scientist Bruno Basso is testing a UAV outfitted with near-infrared, thermal and lidar sensors to examine new sensor uses that could benefit management of crops. Photo courtesy MSU

Thermal sensors might provide unique insights that help fine-tune understanding of nutrient and moisture interactions, says Basso. They also could improve irrigation efficiency by generating high-resolution soil moisture maps.

Thermal imagery also could provide an early warning of insect and disease infestations, adds Kevin Price, who recently retired from Kansas State University, where he specialized in remote sensing. “When plants are sick they start running a temperature as the plant’s cooling mechanism is impaired,” he says. “With any kind of insect or disease that attacks the photosynthesis system, you will see anomalous temperatures long before you can see a problem with the human eye. I think thermal imagery could be a game-changer.”

The importance of lidar is less clear-cut, says Basso. The lidar sensor on his UAV will be able to measure crop height differences from plant to plant. In conjunction with NIR and thermal imagery, lidar data may help explain how various stresses affect plant growth, and identify strategies to reduce them.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like