Madhu Khanna, distinguished professor of environmental economics at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, says that CRP acres have the potential to produce harvestable bioenergy crops.

Speaking at a Council on Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics webinar earlier this year, Khanna addressed the food v. fuel debate and looked ahead to second generation biofuels. She has been doing research in the area of land use and environmental impacts of biofuels for around 15 years, starting in 2005.

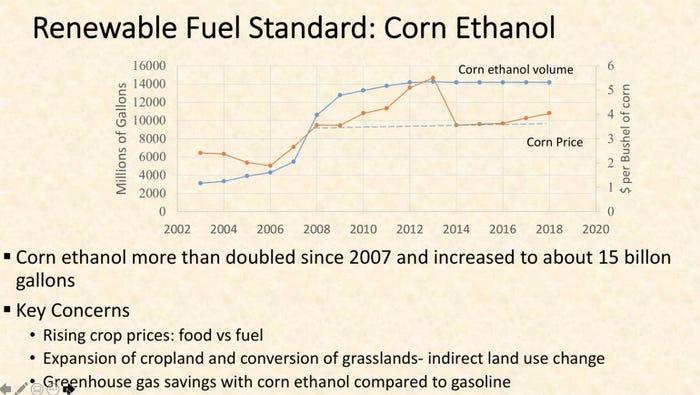

The Renewable Fuel Standard was the major policy driver that stimulated biofuel production in the United States, Khanna said. It has been responsible for more than doubling the amount of ethanol that is produced in the U.S. from about 6 billion gallons in the mid-2000s to close to 15 billion gallons today.

As production increased, the concerns did as well. The biggest concern was about the increase in corn prices, with prices more than doubling in the five to six years following enactment of the RFS. There were concerns about food being used for fuel, grasslands being converted to cropland and whether or not biofuels would achieve the promise of greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Over the last 15 years or so, economists have been exploring the role of corn ethanol in influencing the land use changes.

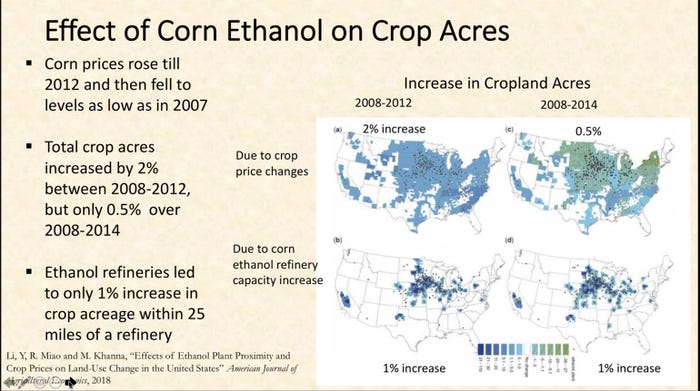

"One of the things that we look at is the spillover effects that might not be evident immediately," Khanna said. She found that by 2014, corn prices had fallen to almost 2007 levels, while ethanol production remained at close to 15 billion gallons. What research has shown is that only a small portion of the increase in crop prices was attributable to ethanol, as other factors, including as increase in oil prices and increasing demand from China also influenced prices.

Land use

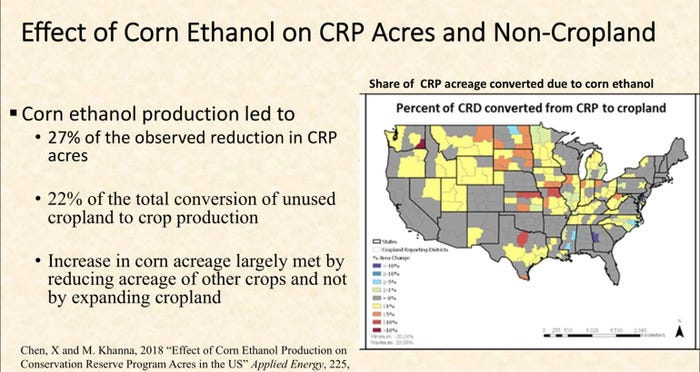

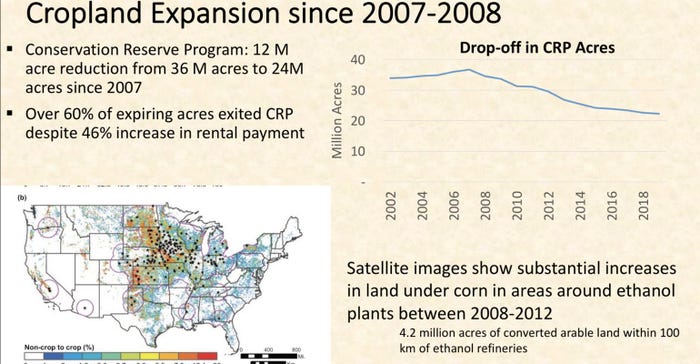

There was also a 12-million-acre reduction in CRP even though rental payments were going up. Research found that only 27% of the land that left CRP could be attributed to corn ethanol, Khanna said.

Land use change is influenced by changes in crop prices, not only in the U.S., but around the world, Khanna said, and this can lead to increased carbon emissions because of deforestation and conversion of grasslands to cropland. This conversion may erode savings from displacing fossil fuels in the U.S., but these estimates have been declining and studies have shown the impacts may be significantly smaller than when the research started in 2007.

There's also a trade-off with water quality, because while ethanol can reduce carbon emissions, the increase in corn production results in more nitrogen usage, which can lead to more nitrate runoff and worsen hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico.

How do we weigh these trade-offs?

There's been a lot of research funded by the federal government and other sources into second generation biofuels, Khanna said, though they haven't yet met the goals set out in the RFS. Researchers continue to explore the potential to convert high-yielding perennial grasses into biofuels. In the Midwest, miscanthus and switchgrass are the top contenders as they can provide negative carbon fuels. Fuels from these perennial grasses reduce carbon emissions related to gasoline by more than 100%, reduce soil erosion and nitrogen runoff, and are grown on low-quality land. It is more costly to convert these grasses to ethanol and the nation's biofuel policy needs to take this into account, Khanna said.

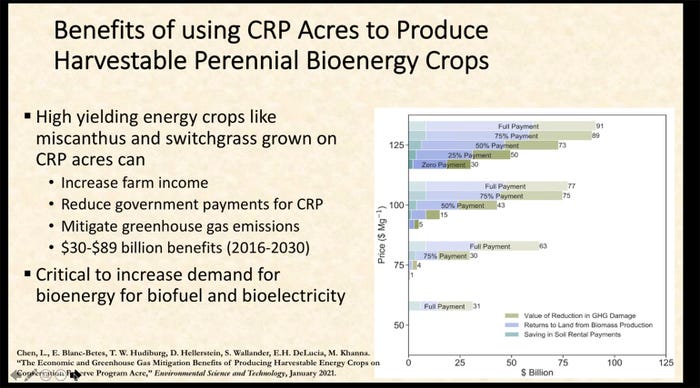

The benefits of using CRP acres to produce harvestable perennial bioenergy crops include increasing farm income, reducing government payments for CRP land and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

"There's evidence that agriculture has the capacity to respond to higher demands and higher crop prices with technological change and increasing productivity," Khanna said.

The RFS mandate grows to 36 billion gallons in 2022 and the EPA determines the renewable fuel volume after 2022.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like