In the first three parts of this series we identified agriculture’s responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions, and some solutions. Another way to lower overall GHG is through viable carbon trading platforms. In effect, farmers who do specific practices would participate in carbon trading markets and get paid to store carbon and build soil health.

These trading platforms are based on a global movement among companies and governments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

How it works

So, what is a carbon offset, anyway? Companies “offset” their carbon dioxide emissions by purchasing credits as tradable certificates. The idea is that the cost works as an incentive for some companies to evolve practices that reduce carbon emissions, and it incentivizes others to reduce emissions by creating a way to monetize those efforts (more here).

Another approach is carbon credits. “The environmental footprint of agriculture is important to socially conscientious food brands,” says Debbie Reed, executive director, Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, a collection of agriculture and food companies as well as nonprofits working to establish a voluntary market for payments to farmers for ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and water quality improvement. “It costs farmers and ranchers money to provide these ecosystem services that we ask of them. It’s another product that they provide for us. We should pay them for it. A way to do that is through carbon credits.”

Companies like Indigo, which started as a microbe-based seed coating business, have launched Indigo Carbon; farmers determine where they are at currently with sequestered carbon, create a plan to sequester more carbon, execute and verify the plan, then get paid. According to Owen Poindexter at Greenbiz, Indigo Ag will measure your farm’s carbon five ways. Two of those — cover crops and use of manure as a fertilizer — absorb more carbon directly. The other three — increasing crop rotation, using no-till practices and reducing chemical fertilizers — release less carbon to begin with. Locus Ag Solutions, which sells a probiotic soil amendment that allegedly reduces carbon footprint, has partnered with carbon removal marketplace Nori to pay farmers for sequestration through something called CarbonNow.

(Read more about emissions trading here. Keep up to date on carbon trading with this newsletter.)

As our Kansas colleague PJ Griekspoor reports in this story, General Mills established a three-year pilot project working with Kansas farmers to teach regenerative agriculture practices. Why? “Central and western Kansas are critical sourcing regions for us,” says General Mills soil scientist Steven Rosenzweig.

One of the project’s goals will be collecting data that quantifies the benefits of regenerative agriculture practices such as no-till, cover crops, increased plant diversity and adding livestock.

Weather-proofing your soil

Besides holding more carbon, such practices make your soils more capable of absorbing and holding more water, and better able to withstand extreme weather events such as heavy rainfall or drought.

“General Mills has a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 28% across its full value chain by 2025,” Rosenzweig says. “More than half of our carbon footprint comes from agriculture. This gives us an opportunity to measure reductions in our emissions, both by greater carbon sequestration and by reduced emissions from agriculture. As part of the pilot, participants who opt into data tracking and field measurements will be some of the first in the country to be paid for sequestering carbon or improving water quality through this market.”

The connection between wheat growers and a major cereal maker is clear, but other less obvious companies like JetBlue, Amazon and Microsoft have also set public goals to slash carbon footprint. These promises are the result of demand from shareholders, and commodity organizations are watching carbon market development closely.

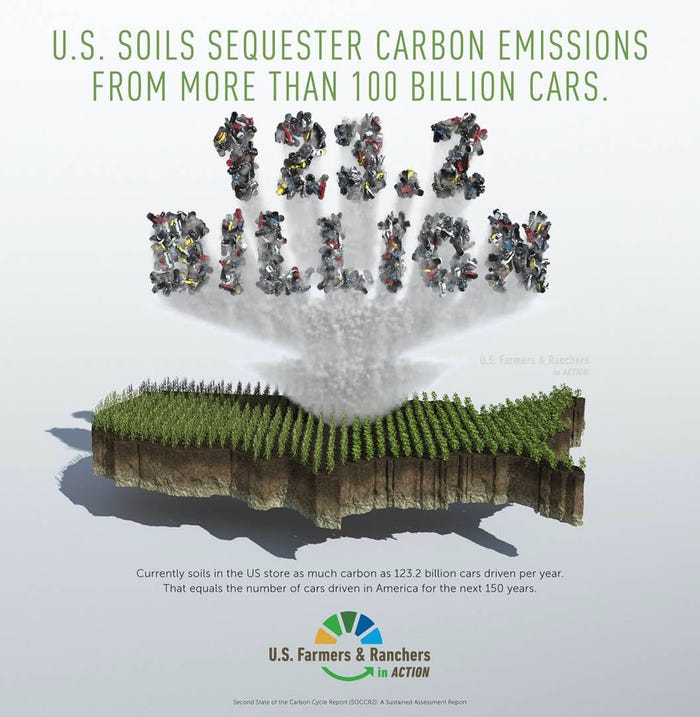

“Agriculture is the only industry which sequesters carbon in the course of normal business operations,” says John Duff, strategic business director for National Sorghum Producers. “Accordingly, we must work hard to ensure U.S. farmers are compensated for this valuable service.” Read more of Duff’s take on carbon markets here.

Other leaders say the concept still needs work.

“I don’t think too many people are ready to buy in to this,” says Dave Milligan, National Association of Wheat Growers president, talking with reporters at the 2020 Commodity Classic in February. “There’s a lot of unanswered questions. You want to make sure it’s reputable and that you get paid. There’s interest in setting up standards, but I think we’re quite aways away from this being effective.

“If you’re really serious about climate change and all you’re doing is selling what we already do to someone else, it’s almost like paying to pollute. It’s not solving the problem.”

Even so, Congress seems to moving toward establishing legislation to formalize carbon trading. The one story to watch is coming from the bipartisan-supported U.S. Senate’s Growing Climate Solutions Act, explained here.

Coming in part five: Are burping cows really a threat to humanity

Missed some content in this series?

Part one: Will farmers get paid to save the planet?

Part two: What’s at stake in the debate over climate change

Part three: Synthetic fertilizer is a modern miracle but it’s wrecking the atmosphere. Can we do better?

Part four: Is carbon trading an answer?

Part five: Are burping cows really a threat to humanity?

Part six: Farmers, tell your story

Read more about:

ClimateAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like