May 3, 2022

The dairy industry in Nebraska and in the U.S. has transformed dramatically over the years in response to changing economics, productivity and consumer demand.

The federal dairy policy framework also has changed dramatically, from a complex milk marketing order and federal price support system to a still complex marketing and pricing system, with federal income support and risk management tools available to producers.

When foundational U.S. dairy policies were implemented more than 70 years ago, milk production and consumption were more confined to regions or “milksheds,” given the importance of fluid milk consumption and the logistical constraints of transporting a perishable product over long distances outside of a local region.

As transportation and refrigeration advanced and more marketing moved beyond local areas, milk marketing orders and pooled pricing mechanisms across classes of milk were created in the 1930s to help farmers facing low milk prices, while the dairy price support programs date to the 1949 Farm Bill.

Big changes

However, there have been many changes in the dairy industry in both supply and demand since that time, creating challenges for traditional dairy policies. Fluid milk consumption per person has been declining since the 1940s as demographic and generational changes in the U.S. population have affected consumption patterns, along with the growing market for other beverages and even the competitiveness of other breakfast options versus dry cereal and the milk that generally went with it.

On the other hand, cheese consumption has grown substantially. USDA-Economic Research Service data shows fluid milk consumption per person declining more than 40%, while cheese consumption grew more than 110% per person over a 45-year period from 1975 to 2020.

The shift from fluid milk demand to manufactured dairy products changed the relative importance of regional markets vs. national and even international markets. At the same time, productivity gains, economies of scale and milk manufacturing market growth have encouraged growing herds and concentration of production across the country and across Nebraska as well.

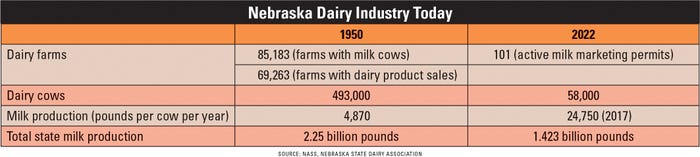

In Nebraska, the dairy herd has fallen almost 90% since 1950 (from 493,000 cows in 1950 to only 58,000 cows in 2022), and the number of dairy farms has fallen from about 85,000 farms in 1950 (when most farms had at least one dairy cow) to 101 dairies with active milk marketing permits.

Despite the dramatic decline in dairy cows and farms, growing dairy herd productivity from less than 5,000 pounds per cow per year in 1950 to nearly 25,000 pounds per cow per year in 2020 meant that total dairy production in the state has recovered to more than 1.4 billion pounds in 2020, the highest levels since the early 1970s (and about half the record production levels from record herds in the 1930s).

Shifting policy

As the production systems have shifted, the relevance and design of dairy policies has shifted as well. The milk marketing orders and pooled pricing systems remain in place, but the dairy price support system tied to dairy product purchases to support a minimum milk price has shifted.

The inclusion of the Northeast Interstate Dairy Compact in the 1996 Farm Bill introduced an income support mechanism tied to a target milk price for dairy producers in the six New England states at price levels above the underlying price support mechanism.

The program for milk producers worked much like the target price and deficiency payment system for grains, which ironically was eliminated in the same farm bill in lieu of guaranteed, fixed payments. NIDC became a model for the Milk Income Loss Contract program in the 2002 Farm Bill and extended the target price system nationwide.

The 2014 Farm Bill ushered in a substantial change in the dairy safety net, eliminating both the dairy price support system and the MILC program in favor of a margin-based safety net, with protection tied to the price of milk less the cost of feed.

The Margin Protection Program for Dairy provided insurance-like protection for producers for a milk price-feed cost margin from $4.00 to $8.00 that could be selected and purchased for a set premium rate (with separate rates for milk production up to 5 million pounds annually and milk production over 5 million pounds).

The 2018 Farm Bill further revised and renamed the program to the Dairy Margin Coverage program with expanded coverage options up to $9.50 margin protection and adjustments in premiums (generally less than in MPP for under 5 million pounds and generally more than MPP for over 5 million pounds).

Beyond the formal dairy safety net programs included in Title I of every farm bill, dairy producers also have relatively new insurance products available to manage either milk price risk or milk price-feed cost margin risk.

Dairy Revenue Protection was introduced in 2018 and provides a price risk management tool available through insurance agents that bases protection on dairy product futures prices. The Livestock Gross Margin insurance policy for dairy has been around longer and protects the milk price-feed cost margin, but has received limited interest as it was restricted to those not simultaneously enrolled in the MPP program. The 2018 Farm Bill relaxed the restriction on what is now DMC and LGM-Dairy, and there is potential for interest in LGM-Dairy to grow.

A key difference between the safety net and insurance programs is that the DMC program charges a legislated premium rate that is larger for larger levels of margin protection and for larger operations. The DRP and LGM-Dairy insurance tools are priced according to price volatility in the market, but premium costs are partially subsidized by the federal government, similar to crop insurance.

The numerous changes in dairy policy over the past 70-plus years from milk marketing orders (which still exist) and price support programs toward margin-based risk management programs and insurance products have been both a response to the changing economics of dairy production and consumption, and a reality as policymakers address shortcomings and inefficiencies in existing dairy policy.

What’s ahead?

Questions about dairy policy will show up again in the 2023 Farm Bill debate that is just underway. There will be questions about the mix of safety net tools and insurance tools and about the adequacy of margin coverage in a period of high milk prices and high feed costs. There also will be questions about the continued concentration of dairy production, as well as processing and marketing.

While those may be the issues on the table, one of the more interesting questions will be who becomes the congressional champions of dairy policy. For years, Sen. Pat Leahy of Vermont rode herd on dairy policy and was the father of the Northeast Interstate Dairy Compact. However, he is retiring at the end of the current session and won’t be there for farm bill debate in 2023.

In the House, Collin Peterson of Minnesota was a primary driver of dairy policy, including the development and revisions to the margin-based DMC safety net program. But Peterson is also gone, having retired at the end of the last session of Congress in 2021. Thus, new directions and drivers for dairy policy remain a question heading into the 2023 Farm Bill debate, with dairy producers and dairy interest groups certainly working hard to cultivate established relationships and build new connections.

Similar efforts are happening here in Nebraska, where policy discussions may not be about safety net tools, but still are happening — with a focus on economic and environmental policies such as siting requirements, regulatory and approval processes, and economic incentives for new dairy production and processing.

Lubben is the Extension policy specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like