Former Sen. Pat Roberts of Kansas neatly summed up the carbon market concept as he spoke to ag journalists in Kansas City last month: “Carbon in the air, bad; carbon in the soil, good.”

Ah, if it were only that simple.

Turning that concept into reality through a carbon market — and paying farmers to do it — is not as easy as it sounds.

To be sure, carbon markets offer tantalizing win-wins for agriculture. They could spur farmers to adopt practices that improve soil health, reduce global warming and even pay growers for adopting those changes. So why isn’t everyone jumping on the bandwagon?

Let’s count the ways. But more important, what needs to happen to make carbon markets easy for farmers to understand and embrace?

The concept

Carbon markets, particularly offset markets, are not well established, but the potential is huge. The 244 largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters in the world discharge between 32 billion and 34 billion metric tons a year.

Carbon markets work like this: Some companies that pollute — which is nearly all companies in one way or another — have pledged to become carbon neutral at some point. One way to do that is to pay into a market (or exchange) that provides credits, or offsets, for their carbon behavior. In theory, this compels the company to make changes to its carbon footprint over time so it can reduce these payments.

Farmers, on the other side of that exchange, have a unique ability to adopt soil and eco-friendly practices like no-till and cover crops that take carbon dioxide out of the air and stash it in the soil. They generate “carbon credits.” As part of a carbon market, they adopt carbon-stashing practices, monitor carbon sequestration in soil over time and get paid for it through the exchange.

Some farmers already participate in programs, but many more have said wait just a hot minute. There’s a lot of fuzziness that keeps this idea from taking off.

Clarity needed

Let’s start with farm attitudes about carbon markets. In a spring Farm Futures survey of just over 1,000 farmers, 41% “completely or somewhat” supported public or private programs that would compensate their farm for engaging in climate-friendly practices. Three out of 10 said they “somewhat” supported the idea, but 29% had not much, or no support, for the concept.

Even the supporters in the survey wanted to know “what is the learning curve,” and “if there are strings attached,” and needed proof they would be fairly compensated.

One respondent said, “Costs will be added to my business as I make the changes to my operation in order to comply with climate-friendly practices. … Receiving compensation to help offset these expenses will make adaptability less of a burden to my business.”

The survey also revealed plenty of skepticism. Many of those surveyed weren’t even sure any such program would actually reduce greenhouse gas. “Does any of this stuff work?” asked one respondent.

Show me the money

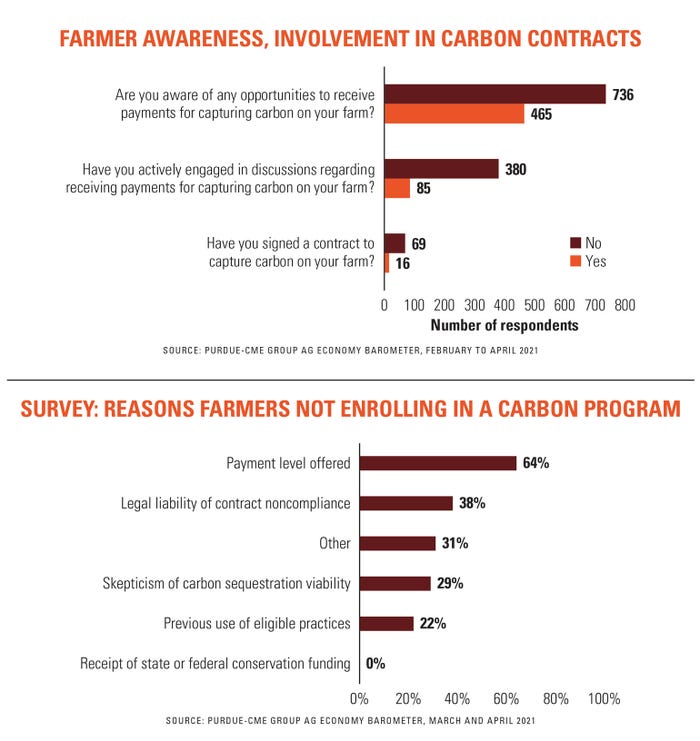

A more recent Purdue-CME survey of 400 large-scale commercial growers (1,201 responses over three months) says the carbon deals — so far — aren’t worth it.

The study indicates 41% of farmers were offered $10 to $20 per acre to sequester carbon; 43% were offered less than $10 per acre. About 11% were offered $20 to $30 per acre, and 5% were offered over $30 per acre. But a 2018 study showed that Indiana farmers would have to get about $40 per acre, an amount that should compensate for increased costs and potential yield drag, to make it worth their while to switch from conventional to no-till, one of the key sequestration-approved practices.

Patchwork Protocols

Another roadblock is the patchwork of protocols initiated by the many different companies and agencies working as carbon-removal facilitators in non-regulated voluntary markets. These companies are both familiar (Bayer, Corteva, Nutrien) and less familiar (Indigo Ag, Nori).

The Environmental Defense Fund and the Woodwell Climate Research Center reviewed 12 published protocols that have been approved since 2011 with the intent of generating soil carbon credits. Each protocol sponsor takes different approaches to measuring, reporting and verifying net climate impacts, and the majority of protocols have not generated any marketable credits to date. The result: a confusing marketplace where it is difficult to compare credits or guarantee that climate benefits have been achieved.

“Until these variations can be resolved, paying farmers to sequester soil carbon will remain an uncertain approach to greenhouse gas mitigation but can still deliver important benefits for climate resilience, soil health and water quality,” notes the EDF-Woodwell review.

“We need credible, consistent and cost-effective measurement and verification to know with confidence that soil carbon credits are moving us toward that target,” says Emily Oldfield, EDF agricultural soil carbon scientist.

Big potential, roadblocks

Scientists estimate farm soils could remove 4% to 6% of annual U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Converting from conventional till to no-till is one way to get there. The 2017 Census reveals that some 26% of U.S. cropland is in no-till. If all cropland acres were converted to no-till, 123 million metric tons of carbon per year, or 2% of all U.S. carbon emissions, would be sequestered.

What about cover crops? That’s where most farmers can make the most impact in carbon payments. Only 4% of U.S. cropland acres are planted in cover crops; cover crops on all crop acres would sequester 147 million metric tons of carbon per year, or 3% of all U.S. carbon emissions.

But soil carbon remains difficult to measure for countless reasons. While scientists understand how soil carbon responds to farm management changes, scientists cannot predict sequestration with the accuracy and certainty required by a market. Detecting soil carbon changes over time requires sophisticated soil sampling and analysis, which can be costly and may need to be collected from different soil depths depending on soil type and conservation practice used.

“It’s no accident carbon markets have not involved agriculture,” says Purdue ag economist Carson

Reeling. “It’s hard to tell how carbon changes from year to year. We’re not sure what we’re measuring or how consistent it is.”

According to Cristine Morgan, chief scientific officer at the Soil Health Institute (SHI), soil scientists know what and how to measure soil carbon. The trouble is the cost of measuring it to get the certainty required in a market. But that could be changing.

“There are exciting new research efforts and technological developments underway that will greatly reduce the cost of verifying soil carbon credits,” says Jonathan Sanderman, associate scientist at Woodwell. “Increasing accuracy at scale, while also being able to pass on most of the value of a carbon credit to the farmer, is critical to ensuring functioning carbon markets.”

Also consider that soil’s capacity to hold carbon isn’t infinite. You can only jam so much carbon into soil, Reeling says. And it’s usually adding carbon at a higher rate at the beginning of this sequestration period, but less so as time goes on. “There’s a limit to how much and for how long this will be effective,” he adds.

Morgan says there are two ways to verify a change in row crop soil carbon: measure the carbon, which is expensive, or modeling, which is too uncertain. The ultimate solution to verify carbon will likely be an ensemble of both, she adds.

Further complicating any validation effort over time is the fact that soil carbon varies in space and depth. “Try to visualize a soil sample coming out of a field,” she says. “We need to know the concentration but also how much soil was measured. So we take the same core sampler and collect samples across a field, and then try to figure out how much has changed over time. We don’t want to have to take a sample and send it to a lab because that’s time- and cost-sensitive. And we have to measure consistently.”

SHI is developing a simple and easy tool to verify and measure soil carbon based on a DeepC pene-trometer. “You get easy data acquisition that goes to precision modeling to a carbon stock estimate, then optimized spatial sampling,” Morgan says. “We need to optimize our spatial sampling to reduce the cost of verification. We need certainty, so we can take a lot of certain and expensive soil cores, or we can use a less certain method but measure in many more locations. We want the data to be easy to acquire.

“Right now, the markets are signaling that they recognize, early on, that we might be too uncertain about the verification process,” she adds. “But there is room to innovate and develop better measurement technologies that can decrease the cost. We hope the markets can accelerate management changes.”

Supporting early adopters

Another twist in the carbon confusion is the fact that carbon markets do not currently reward farmers for the carbon they may have already captured through the adoption of conservation practices like no-till or cover crops. This is called “additionality.” Carbon market participation today can only pay farmers what they can prove now and into the future, not going backward.

Conservation programs today, such as the Conservation Stewardship Program, pay farmers for actions they take like no-till or reduced nitrogen use, which also provide environmental benefits. Those same programs could be expanded, as focus shifts to providing more government incentives to encourage climate-smart agricultural practices and rewarding environmental champions.

Stakeholders in Washington are trying to determine if the government’s Commodity Credit Corporation funds can be used to provide some compensation to farmers who already do the right thing. Legislators are looking for ways to enable those early adopters to keep leading, and boosting conservation funding may be one way to do

accomplish that goal.

Early days

These are early days for carbon markets. It’s best right now to keep an eye on what’s happening in Washington. This summer the U.S. Senate passed the Growing Climate Solutions Act, which would provide a regulatory framework and confidence that the marketplace’s protocols will be vetted and secure. As of August, the House has yet

to take it up.

GCSA would set up a third-party certification process through USDA. The agency would provide a stamp of approval for those third-party groups already in the carbon market, and in theory, build farmer trust. It would bring more transparency to the carbon market and more clarity on farmer requirements, eliminating some of the wild, wild West confusion seen today.

“At some level, government will have to step in and actually coordinate all this,” Reeling says. “If you leave it to a bunch of companies, there will be a lot of issues.”

The real benefits

While everyone fixates on payments and protocols, let’s not forget that soil organic carbon can improve

a farm’s resilience, especially in the face of worsening weather events. Soil health practices like no-till and cover crops do increase carbon sequestration, which then increases plants’ water-holding capacity and makes the crop more resilient.

Even before entering a carbon program, you can start to keep track of your good soil practices with the data you have now to provide a baseline for the future.

If you’re worried about the risk of adopting new practices, consider the risk of doing nothing. Weather extremes, including 10-inch rains in two hours, aren’t going away soon. Pay attention to carbon markets and adopt soil health practices — either for the money, or because it could help your farm’s soil base. Hopefully, both.

Read more about:

Carbon MarketAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like