Low input costs. Low machinery costs. And high dividends. The perfect recipe for success on the farm today.

Young farmer Will Glazik, along with brother Dallas and father Jeff, continues to perfect that concoction over the last five years on his organic 1,000-acre farming operation near Paxton, Ill. He’s added his own distillery, as well as hogs and cattle, to diversify his growing income stream fueled by growing organic demand.

“There’s a lot of farmers out there who are getting by, but it’s not enough of a salary to bring on another person,” Glazik says.

Without the high margins he’s capturing in organics today, it’s unlikely he would have been able to return back to farm on his own.

Glazik looks at his diversified business as a pyramid. “We sell a little bit of grain at really high values. And then it kind of works its way down to where you can always sell bulk at lower margins. I don’t buy many inputs.”

When conventional farmers spend $50 to $120 per acre on herbicide and fertilizer, as well as seed costs, Glazik spends just $60 an acre every four years on manure and an additional $25 to $60 per acre per year on cover crops. And he saves seed from some of his open-pollinated corn, soybeans, wheat, cereal rye and oats for subsequent years.

Positive market dynamics

Ken Dallmier, president and chief operating officer of Clarkson Grains in Cerro Gordo, Ill., says organic farming requires a real mindset change in how farmers think of themselves being successful. Instead of looking at big yields as the measure of success, focus instead on how to maximize net income.

The traditional corn-soybean rotation over the past five years yielded a net income of a mere $2 per acre, compared to $200-per-acre net income for organic, Dallmier says. “The market is screaming for people to participate. There’s a market opportunity [that]with some planning, anyone should be able to handle.”

Ryan Koory, director of economics at Mercaris, says organic demand growth predominantly stems from the livestock sector; however, it isn’t as simple as a one-to-one replacement of current organic corn and soybean imports with domestic production. The supply of U.S. organic soybean meal increasingly relies on foreign supplies, with U.S. 2018-19 organic soybean meal imports expected to increase 35% year over year.

“Even though we import 70% to 75% of our domestic organic soybean needs, increasing organic soybean acres at 300% will dump excess soybean oil into the conventional market because of a disconnect between organic oil and organic soybean meal markets,” Koory says.

Also, increasing soybean acres would require a bump in other organic rotations crops, which could create downward pressure on feed-grade oats, rye and barley. “If we only focus on increasing soybean acreage to displace imports, and not overall organic crop demand, we will end up doing more harm than good to the U.S. organic industry.”

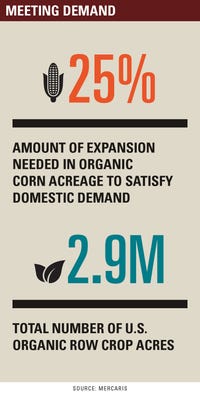

Meanwhile, to meet domestic organic corn demand, producers could increase organic acres by 25%, which Koory also says is a reasonable market opportunity for domestic producers in the next few years.

Domestic organic corn production increased 2% from the prior year. And imports of organic corn have slowed for both whole and cracked corn, although imported organic grain is putting downward pressure on the domestic price for organic feed grain.

Koory says after bad press from mislabeled organic shipments out of Turkey, imports of whole corn nearly completely shut down.

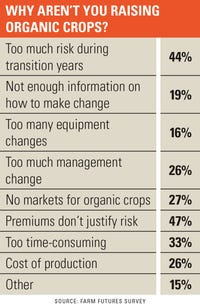

When we asked farmers in 2018 why they don’t grow organic crops, 51% said the premiums don’t justify the risk, and 48% said there was too much risk during transition years. Around 30% said there were no nearby markets for organic crops.

“For growers to make a transition within the ag supply chain today, there are a number of challenges for a system not built to handle organics,” says Andy Vollmar, director of food ingredients and specialty grains at The Andersons in Maumee, Ohio. A farmer typically sells to the local co-op or elevator; the change to organics requires longer transport time.

Even so, companies up and down the supply chain are stepping up to offer more solutions for organic farmers.

The Andersons’ Waterloo, Ind., facility continues to serve conventional growers and dealers, but now has a portion dedicated to supplying nutrient products approved by the Organic Materials Review Institute.

From the new warehouse, dealers and growers can access a variety of organic-approved products, including primary nutrients, soil amendments, granular micronutrients and enhanced efficiency products.

Glazik says he’ll look to add one of The Anderson’s corn starter products that offer a boost for organic corn’s early development.

Danielle Kusner, agronomist at The Andersons and transition consultant, offers one-on-one service to assist with crop rotation, tillage suggestions and weed control, as well as helping new growers walk through the organic paperwork.

Giving back to the soils

Organic requires more thinking about the soil and future crops. “I have to think about how my current practices are going to affect my crops three, four and five years down the road,” Glazik says. “And there are no rescue treatments for weeds, insects or diseases. You have to keep a preventative mindset, and that can be a challenge to wrap your head around when you’re coming out of a conventional system.”

In early June when farmers across Illinois were racing to get crops planted during a dry spell, Glazik was mowing a field mix of alfalfa, clover and volunteer wheat to offer a fertility boost to the organic crop he was about to plant.

While most farmers would want to bale that hay crop, Glazik recognizes it makes great food for the soil and will give him dividends for years ahead.

“I want to give it back,” Glazik says of the desire to look at what he can naturally add to the soils. He plants cover crops and runs a drill pretty much year-round.

His operation consists of 250 acres of organic corn, 250 acres of organic soybeans, a green fallow rotation that does not get harvested, and small grains, including oats, rye and wheat.

“I encourage people to raise diverse crops and find diverse markets,” Glazik says.

The green fallow rotation offers the weed control, fertility and pest management program. Glazik also uses a roller crimper to kill cereal rye before no-till planting organic soybeans. This creates a thick weed barrier mulch, which retains moisture through long, dry periods during summer. “If you want to have a long-term system, you really have to be generous with your soil.”

More food per farm

Glazik looks at ways that he can raise more “meals” on his farm, and not just bushels.

An on-farm corn flaking mill, with the open-pollinated corn he grows, could yield 1.7 million bowls of cornflakes, even at the average 75-bushel-per-acre yield, he says. That’s enough to feed breakfast to his hometown every day of the year. Right now, farmers only capture 20% of the value of organic crops they sell, with 80% going to the middleman.

“When we go direct from the farm to the consumer, we capture all of it,” he says. “But we also have to do all the work.”

The value Glazik brings back to his bottom line from the distillery is “tremendous,” he says.

With just 30 acres, he uses soft red winter wheat for the vodka and rye for the whiskey, and is trying open-pollinated corn for a bloody butcher bourbon. He also sells to other local distilleries and breweries, and a miller for cornmeal and other food products.

“When you can look your consumer in the eyes, and you know that what they’re eating or drinking comes from what you produced, it gives you a great sense of pride,” he says. “It also gives you encouragement to try to do better and to make the healthiest, tastiest food you can.”

That’s a recipe that should satisfy consumers and farmers alike.

Interested in learning more from these experts? Email [email protected] or [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like