Editor’s note: I wrote this column last week, scheduled to post this week. Yesterday, my father was called to his eternal home. I hope this serves as a tribute to the families, friends and caregivers of those farmers battling cancer. While those outside of our industry may not understand our need to feed the livestock, move the hay bales and take down cattle panels during difficult times, know that there are those of us in the agriculture community who do.

With 12-foot cattle panels stacked on top of each other, I reached down, grabbed ahold and pulled them to the tree line over the hill. I looked at my husband leaning against a hog hut, arms crossed in front of him. “You done?” he asked. “Not yet,” I replied, tossing the panels aside and walking back up the hill.

It has been a rough couple of weeks. Upon returning from a conference in California, I visited my 75-year-old dad. He did not look well. So we decided to go in for some tests. A hospital stay and outpatient biopsies made for a very long waiting game. And like many farmers, I had to get my stress, anger and worry out —so I worked.

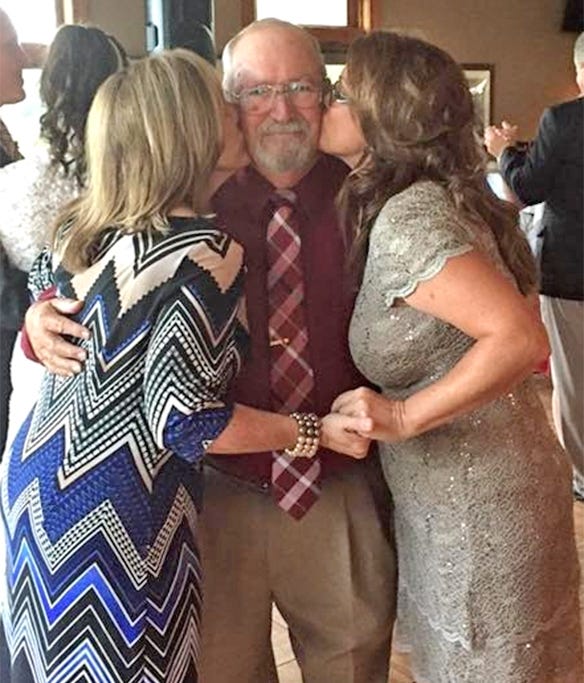

DANCING WITH DAD: We have had three weddings in the family so far, and each one came with a dance with our dad. My sister Thea Etcher (left) and I take time to show him just how much we love and adore him at the end of each dance.

In the barn, we tore down lambing pens, created a creep area, hung gates, cleaned the loft and swept the aisle. We moved from one task to the next with little conversation.

As I headed to the next pasture, my husband followed. There, we removed more cattle panels that once separated market lambs from ewes. They had probably been in place for eight years. I pulled posts and tossed them to the side. My husband gathered the posts and placed them in a neat pile under the lean-to. I heaved cattle panels across woven wire and again made the trek to the bottom of the hill. And with one last toss, I dropped my hands to my knees, exhausted. I was spent, emotionally and physically.

It took two days of work to relieve the stress of weeks. My husband met me at the gate. “You good?” he asked. “I’m good,” I replied.

Times like these make me realize how blessed I am to live on a farm. While others find relief from worry or difficult situations by running, meditating, talking or retreating, mine comes from hard work. It is a lesson I learned from my dad.

Growing up, my dad and I talked through school problems while scraping manure out of the hog house. We discussed my future with a post driver in one hand and fencing pliers in the other. And running laps around the cattle pasture was his way of making me reflect on how lipping off to my mother would not be tolerated.

My dad modeled a good work ethic. When my mom had ovarian cancer, he left for his job every morning at 4:30 a.m. — not because he wanted to but because life had to go on. There were bills to pay and insurance to keep. It did not matter if he wanted to, felt like it or enjoyed it — he worked. So now, it is my turn.

Even with my dad’s diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, I will work. I will tend to our farm. I will write articles. I will comfort my family. I will care for my father. Because throughout his years, my dad taught me hard work combined with faith can overcome worry and fear.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like