Don’t look now, but once-young millennials are starting to sprout gray hairs. And they’re not just from financial pressure after four years of falling farm income.

The generation that pushed its way onto the scene a decade ago is turning 40 and ready to take control of more and more businesses in the U.S., including farms. But talk to millennial farmers and you quickly discover the skills they need to manage the business are much different from their elders’.

“Relationships are a bigger deal now compared to our father’s generation,” says 35-year-old Jordan Klassen, who grows corn, soybeans, alfalfa and cattle with brother Andy, 40, and father Orvil near Mountain Lake, Minn.

“The farm is larger, and the income is similar, but the dollar amounts are much bigger now,” Andy says. “We have to handle a lot more money than our parents’ generation did.”

A decade ago when Farm Futures surveyed farmers, those born after 1977 were hard to find, especially in key management roles. This age group still isn’t a majority in an industry known for being old. But things are changing. Three years ago, for example, Andy and Jordan’s parents rolled everything into a partnership to try to make it more convenient to move the boys into senior management.

“We don’t have a timeline for when we become senior management or majority owners, but that doesn’t bother me a bit,” Jordan says. “Having the ability to gain the equity we’ve gotten in 15 years of farming has been good, considering we didn’t build the business here. We’ve put in a lot of hours, and I trust my dad that he has my best interests in mind.”

Taking command

But make no mistake, millennials are taking command of both decisions and assets. And the rest of the farm population, including Generation X, baby boomers and the silent generation, is also changing.

Millennials made up only 3% of the farm population in 2008. Today, that number is 10%. Boomers are still the most populous, but they’re not quite as ubiquitous. Born in the years after World War II, they’re starting to cash Social Security checks, with the percentage in farming falling from 64% to 57%.

Generation X’ers have a 23% share, up from 13%. The silent generation born before 1946, fell from 21% to 10%, as they retire from active roles on the farm.

To be sure, those silent generation farmers still can speak loudly, and 57% of them say they’re still “head honchos” of their business. But the real shift came with millennials. A decade ago many of these young producers were employees or managers on their family’s farms. Others, a little more than half, shared power. But just 24% said they were the head honchos, a figure that’s doubled today.

Fewer operate by sharing labor and equipment with family members, and more farm by themselves — 17% compared to 6% in 2008. Formal family business arrangements still predominate among millennials — 41% operating in a partnership, limited liability company or corporation with other family members.

As they grew up, millennials grew their farms. In 2008, they farmed an average of 1,125 acres. That’s more than doubled today.

Those from Generation X also grew. Their average nearly doubled to 3,540 in our latest survey. Boomers were little changed over the decade, while older farmers pared back their operations a bit.

Taking charge

As farms grow, a core task is putting the right people in charge of each enterprise. At the Noland grain farm in central Illinois, 33-year-old Grant looks after books and marketing. His brother Blake farms and works as a labor consultant. Their father, Duane, farms and holds an off-farm executive job, and the brothers’ uncle Dennis manages agronomy and equipment.

At the Klassen operation, Andy oversees cattle, while Jordan works on crops and alfalfa. Orvil keeps the books and manages an off-site equipment rebuilding business.

“We’ve done a good job trying to pick strong suits of people, letting them do the work, and having faith that those tasks will be done the right way,” Andy says. “We do bounce ideas off each other, and we help each other out when needed.”

According to our survey, millennials own less of their land than other growers. But ownership among the group is up 10% over the past decade to 31% of the ground they farm.

Buying that land meant more debt, and the group still has the highest debt-to-asset ratio of any. But those with more than 40% debt-to-assets is down from 41% in 2008. Like other farmers, millennials used cash from the boom times to expand, rather than become burdened with loans. And they’re no more likely than others to suffer from negative income, a pain that afflicts farmers regardless of age. Yet because of their higher debt loads, 7% are financially vulnerable.

Work-life balance

Other responsibilities may be weighing on them, too. Some 85% are married, so they’re starting families, and 81% own their own homes, more than double the rate for the age group nationally.

Our survey shows that leisure activities were more important to them a decade ago. But maybe that’s why they enjoy them more, even as other interests faded. They’re less likely to participate in community activities, including farm organizations, or to think that giving back to the community is important. They may be starting to focus on the farm as a lifestyle, not just a job: They’re less likely to believe, “For me, farming first and foremost is a business.”

“My wife is two years younger than me, and we talk a lot about work-life balance,” says Jordan, who has three kids under age 5. His brother Andy and his wife have five children.

“We remember that our dads were not there for us in certain times of our lives, but looking back, I think our parents had it tougher than we did for quite a while. I look at the lifestyle I’m living now and sometimes feel guilty, but I also know I put in quite a few hours and energy in doing what I do. As a generation, we may have gotten lazier on the physical aspects of farming.”

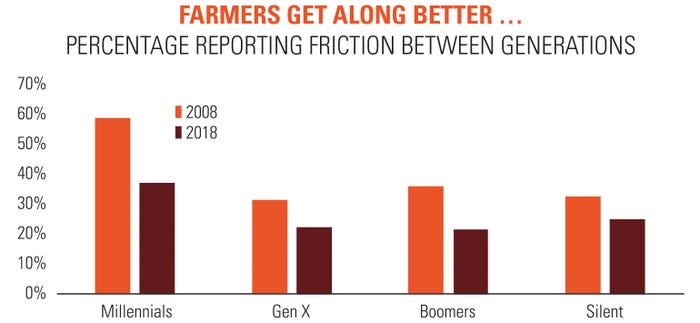

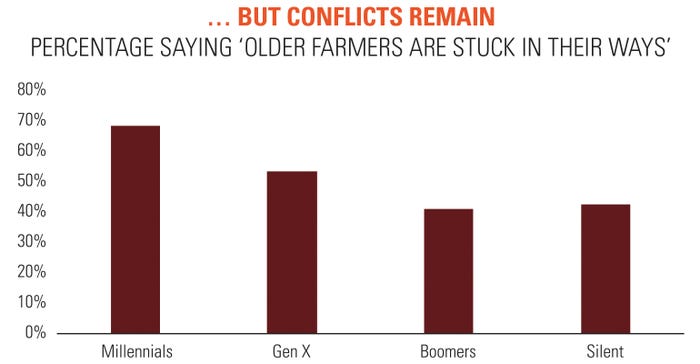

Still, the pressures of the farm business haven’t gotten any easier since our last survey. In 2008, 94% of these millennials agreed that “there’s more to life than just working on the farm.” Today that percentage is down to 85%, while older farmers disagreed. Little wonder 23% of millennials say they work over 72 hours a week, the most of any age group. And differences between generations haven’t evaporated. Two-thirds of millennial farmers agreed that “older farmers are stuck in their ways.”

Yet all ages agree that those conflicts are easing. In 2008, 59% of millennials said there was friction among groups. That’s down to 37% now. All age groups appear to be embracing some workplace concepts more, such as respect, equal treatment and mentoring.

“We all work hard — probably 60 hours a week on average,” says Eric Wappel, 33, who farms with brother Larry Jr. and father Larry in northern Indiana. Wappel is married with two young kids and a third on the way; his brother is also married with four children.

Five years ago, after missing one too many important family events, the farm set a new policy for the three family-owners, as well as their 10 employees: Everyone quits work at 5 p.m. Saturday, and they don’t come back until Monday. “It changed the attitude on the farm,” Wappel says. “Guys work harder and longer because they know they have Saturday date night and all Sunday off to do what they want.”

New challenges

But now that they’re bosses, millennials face new challenges. In our survey, they were the least likely to say the farm has tried to groom younger family members to take on more responsibility. And they also are less likely to believe younger workers can evaluate their bosses. Finding qualified labor is an ongoing concern.

“A lot of people younger than me feel they’re entitled to everything,” Wappel says. “We often have issues with younger kids we hire on the farm. They don’t want to drive the 2005 tractor; they want to drive the new tractor. If you saw the equipment I started out with, you’d drive that 2005 tractor and be happy with it.

“The best thing my dad taught me was, ‘Go to work and earn it yourself,’ ” Wappel adds. “You try to teach the younger guys, but they don’t want to put the extra hours in.”

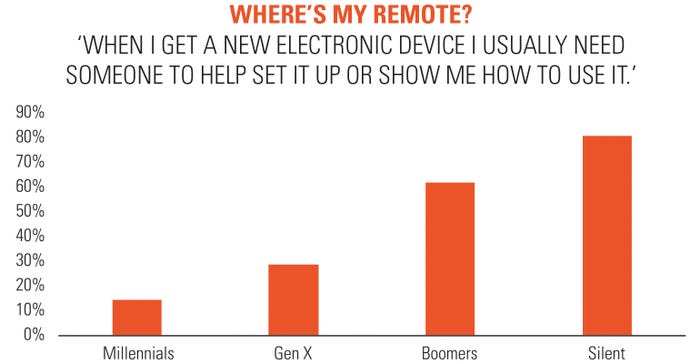

New technology continues to excite a generation born along with the personal computer. Most say they get their news online, likely with a smartphone. And 62% say they check Facebook or other social media at least once a day.

Like many in their generation, they’re more different than the old folks when it comes to approval of same-sex marriage or tolerance of homosexuality. But they’re far less accepting than their peers around the country. While 73% of millennials surveyed in 2016 approved of same-sex marriage, only 40% of farmer millennials did. And 66% believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, compared to 38% of millennials nationwide.

Like other farmers, millennials are much more conservative than the rest of the country. They’re the most likely of any of the age groups to say they’re conservative Republicans — 67% did, compared to 17% nationwide after the last presidential election. And none of the millennial farmers surveyed said they were liberals, compared to 27% of their age group nationwide.

Talkin’ ’bout my generation

Silent generation, or matures, born before the end of World War II. Sometimes called traditionalists or veterans, these older Americans are supposed to prize duty, conformity, authority and sacrifice.

Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964. This is the “Me” generation — materialistic workaholics who, at one point anyway, believed bigger was better.

Generation X, born between 1965 and 1976. Once called “slackers,” these folks value freedom and are said to be skeptical, independent spirits who want to balance work and life.

Millennials, born 1977-1995. These are “echo boomers,” the children of the boom generation who came of age after 2000. Multitasking is their mantra, and they’re defined by social networks like Facebook. They’re said to be more optimistic and hopeful.

Gen Z, born 1996 and later. They’re the first “digital native” generation, born during or after the introduction of digital technologies. They were kids during the Great Recession, so they may lean more toward security and money. They care about making a difference, but they are pragmatic and understand the need for constant skill development.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like