November 8, 2019

Some people like doing the same thing every day. I don’t.

It’s one reason I love this job and it’s one reason covering agriculture in this region is so fulfilling. Sure, I could write about dairy farming, corn and soybeans to my heart’s content. But I like variety.

Case in point: cranberries. These tiny fruits get little media coverage, except for around harvesttime when bogs become red pools of picture-perfect cranberries.

As a farm commodity, though, no one really writes about them, myself included.

So, when I got an email about a cranberry bog tour in New Jersey, I was there!

I, along with a group of other journalists, visited Cutts Brothers Cranberries near Chatsworth, N.J., in the middle of the famed Pine Barrens. The ground is acidic and barren; terrible for corn and soybeans, but perfect for blueberries and, apparently, cranberries.

Cutts Brothers is 128 acres with 27 working bogs.

I was likely the only ag writer on the tour; most of the writers were from daily newspapers and television stations — including a reporter from New York City — who likely have spent little time on an actual working farm, let alone a cranberry operation.

Naturally, I wanted to learn as much as I could about growing cranberries from the farmer, Bill Cutts, who co-owns the business with his brother, Ernest. I wanted to learn how different cranberry growing was compared to other types of agriculture.

I wasn’t disappointed. Believe me, growing cranberries is a unique business. At the same time, though, there are many things Bill has in common with other farmers.

For one thing, the business is family run. Bill and his brother run the business, and every worker on the farm, except for a few seasonal employees, are either blood related or related through marriage.

Like many other farmers, Bill is asset rich and cash poor. He and his brother don’t own the land; they lease it from the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. With land prices being so high in New Jersey, Bill says this is the only way they can grow cranberries and be profitable.

Contrary to what people think, cranberries aren’t grown in water. Like most other crops they are grown in the soil for most of the growing season. Water only becomes crucial when it comes time to harvest.

Different type of farming

But let’s not beat around the bush — or the vine, since cranberries grow on vines — growing these berries is a unique business.

Let’s start with water. Every farming decision Bill and his family make starts with water and how to manage it.

They manage 27 bogs that are flooded twice a year: during harvest and during winter.

Flooding bogs in winter is crucial. Cranberry vines have a shallow root zone, only down to 4 inches. If the ground freezes, the vines take up less water and eventually die. Flooding the bogs ensures the vines have a constant water source to stay alive.

Once April comes around, the bogs are drained and the growing season starts. The vines put out shoots called uprights that produce the fruit. The plants start blooming in June and July.

Bill manages for insects, weeds and fungal issues just like most other farmers. The big difference is that cranberries are a wetlands crop, so most of the pesticides and other tools available to other growers aren’t available to him.

IPM is used to control harmful insects but that’s created its own issues, he says. With no broad-spectrum sprays available, growers are seeing problem bugs and diseases that they haven’t seen in decades, such as the toad bug, which feeds exclusively on cranberries, and cranberry false blossom disease, which decimated New Jersey’s cranberry bogs in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. It causes abnormal flowers that do not set fruit.

The disease is spread by blunt-nosed leafhoppers, which were wiped out by broad-spectrum pesticides. But the use of IPM, he says, has allowed these leafhoppers to re-emerge and for the disease to catch fire again.

Protecting against frost

Irrigating is important to keep frost at bay, which can kill cranberries.

It’s hard to believe, but Bill says he’s seen frost every month of the year, including in July and early August.

Along with its acidity, the Pine Barrens’ sandy soil loses heat quickly, and since the bogs are in low-lying areas, they tend to get colder, about 20 to 30 degrees F colder than Philadelphia, which is about 37 miles away.

Electronic sensors keep track of the temperatures and send a call to Bill’s cellphone where he can then start the sprinklers remotely.

The cold nights are good for color, though, especially as harvest season approaches. More color means more money from the receiving station. But too much cold too early can fool the plants into hibernation, which causes the plants to stop growing.

Expensive to grow

Bogs last a long time but they don’t last forever. Bill says the cost to renovate a bog is between $20,000 and $30,000 an acre to replace irrigation lines and underdrain, as well as plant new cranberry varieties.

His bogs range in size from just over an acre to up to 10 acres.

The types of cranberries grown depend on how the bogs are managed. The bogs are completely gravity flow, so early ripening berries are planted in the bogs that are flooded first.

Self-dependent

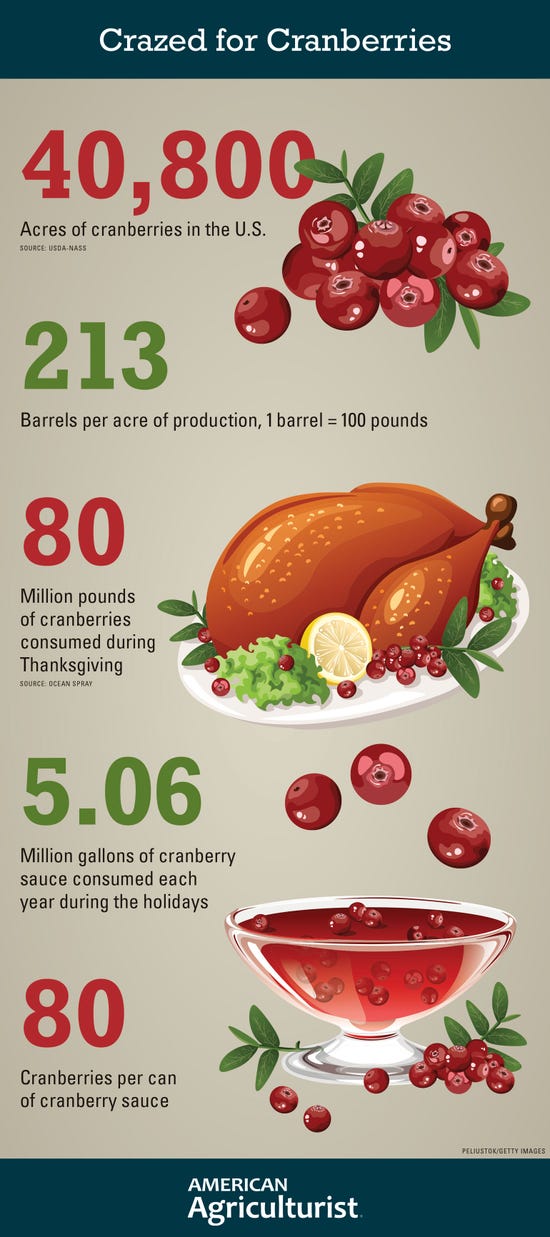

With only 50,000 acres of cranberries growing in the U.S., large equipment manufacturers aren’t lining up to make the next cranberry harvester. Consequently, all the harvesters used at Cutts Brothers comes from a specialty machine shop in Wisconsin, the largest cranberry producing state.

Bill and his family built the pumps used to harvest the cranberries from the bogs.

Harvesttime

Speaking of harvest, Bill will be harvesting berries through at least mid-November.

Harvesting itself used to be done by hand, with workers going out in the bogs with scoops. Mechanical scoops were then introduced, followed by mechanical harvesters.

Water harvesting only started in the 1960s, Bill says. Bogs are slowly flooded and a riding water picker or water reel — nicknamed “eggbeaters” — go in and churn the water to loosen the cranberries from the vines.

Once the bog is flooded, the cranberries float to the top. Oil spill containment booms are then deployed to gather the berries to a pumping machine that washes the berries and loads them in a truck.

So, if you’ve ever wondered where your cranberries come from, your welcome!

All kidding aside, though, hearing a different perspective is always good, whether you’re a farm writer or a farmer.

People say that farmers must get out of their own silos and do a better job educating people about what they do, and that’s true. But you can learn a lot from other farmers, too, so don’t miss a chance to learn.

You May Also Like