September 18, 2020

To say that native plants have deep roots is like saying all Italians are great cooks, all goldfish are gold, and all cats are white with black spots. These statements are sometimes true, but not always.

Plants on Earth have evolved and adapted to grow in almost every environment and soil type. To do this, they have diverse root anatomies. Some roots are fine, dense and shallow. Others are coarse — like jump ropes — spreading out wide, and yet others grow like a carrot, with a trunk that shoots straight down as far as it can go.

Where plant roots grow

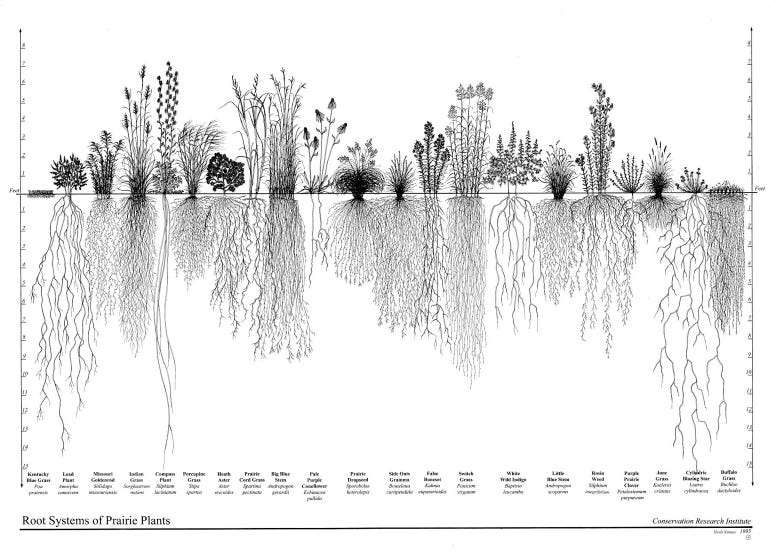

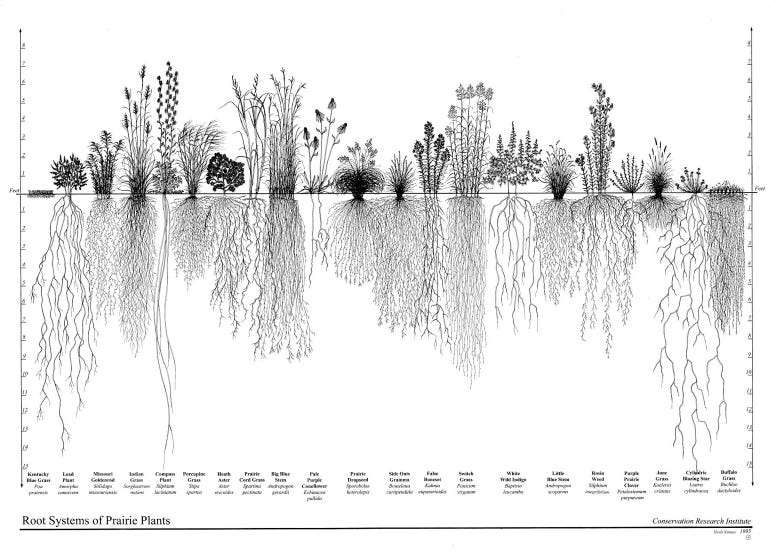

The misconception that native plants have deep roots stems came from studies in the tallgrass prairie region where plant roots were excavated to a depth of 10 feet or more. In many areas of the Midwest, prairie soil is very deep, the result of 10,000 years of plant growth cycles, where roots expanded during periods of optimal growth and died back slightly during periods of flood or drought.

These cycles distributed organic matter deep in the soil column, generating rich, fertile soils throughout the heart of the tallgrass prairie region. Today, it grows the richest corn and soybean crops in the world.

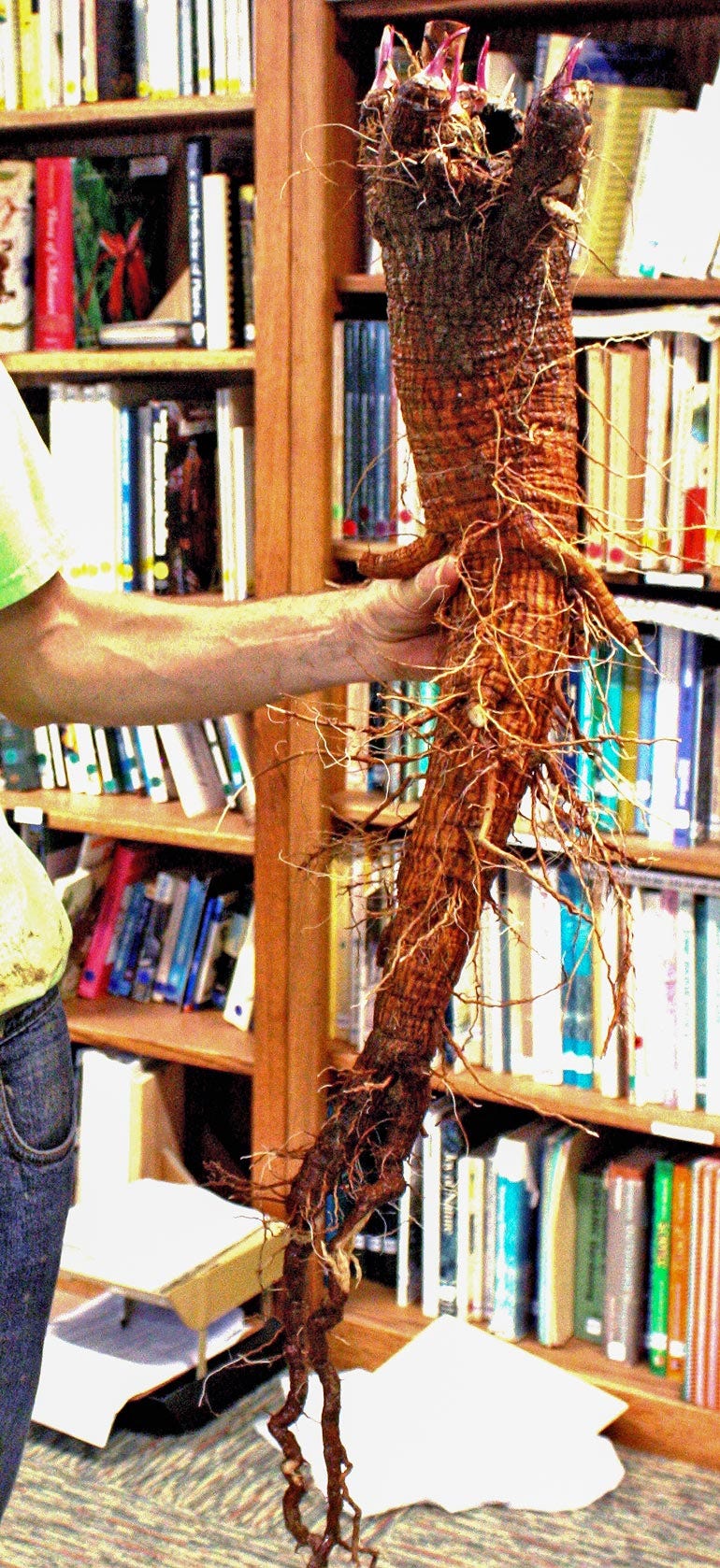

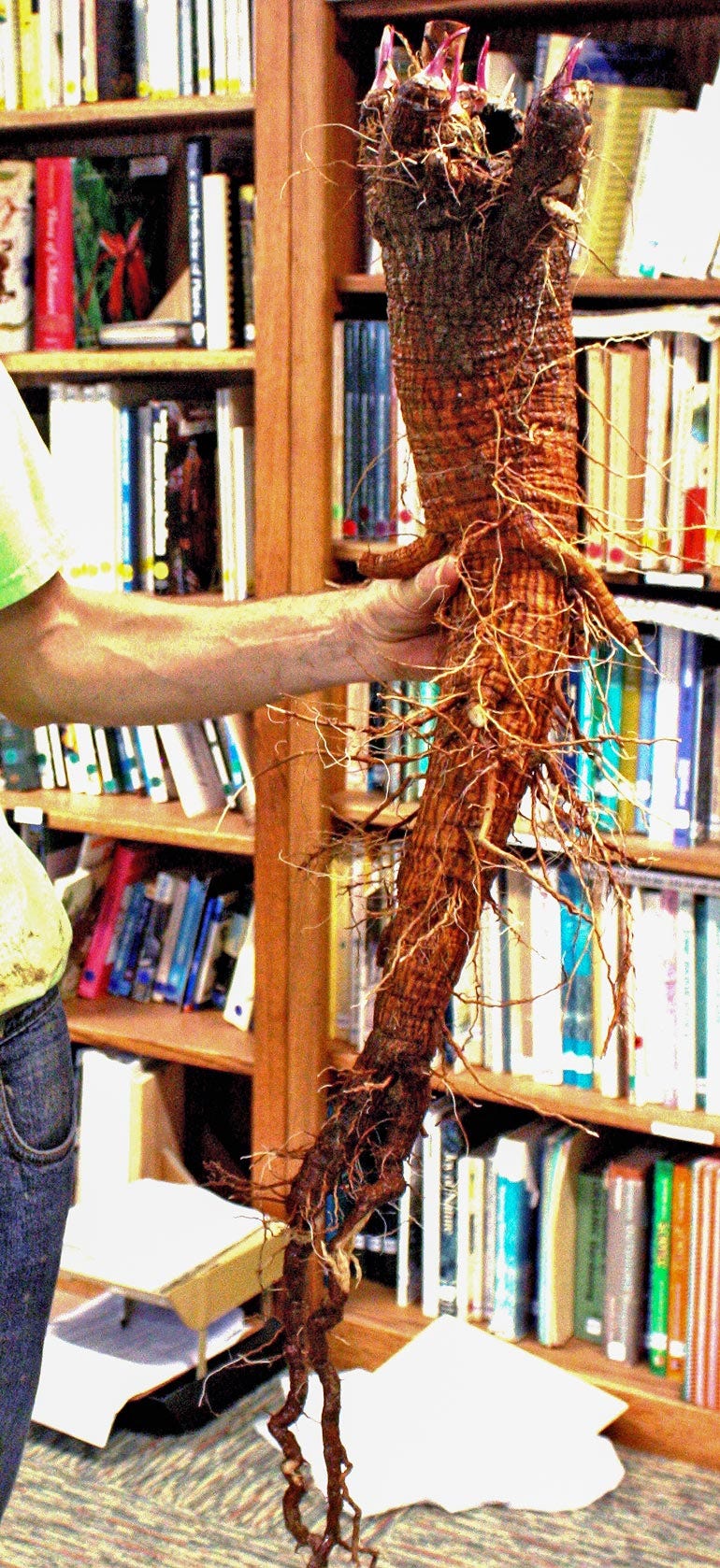

GREAT ROOT: The root of a 15-year-old compass plant (Silphium laciniatum), which was dug from Shaw Nature Reserve with a backhoe.

A more accurate way to look at native plant roots would be to think of each species as being vertically and horizontally territorial underground. For example, there are many species living closely together in ancient remnant tallgrass prairies.

For example, the Missouri Prairie Foundation’s Penn-Sylvania Prairie holds the world record for plant diversity on a fine scale, with 46 native species documented within a 20-by-20-inch frame.

One reason that they can live so close together is that each species is vertically segregated. Some species grow deep, some lie shallow at the surface, and others take the middle ground. The other way they can exist so close together is through horizontal mixing, where coarse rhizomatous root systems weave between fine-textured root networks of other grassland species. And then there are plants that have bulbs, corms and tubers, which are compressed underground plant stems that go dormant for part of the year.

Benefits of dead roots

These plants also are woven between shallow, fine-textured root networks close to the surface. When they go dormant, their roots died back, adding organic matter into the topsoil. All plants do this to some degree.

Underground roots and stems grow and die annually from fluctuating soil moisture, winter freeze and thaw, and interactions with microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, algae, protozoa, and many types of invertebrate animals living in the soil.

Some beneficial organisms transform dead plant roots and stems into usable forms of nutrients. Others graft onto plant roots to form conduits for nutrient and water uptake, and others protect plants against disease and root foraging by pests.

It’s no wonder why diverse tallgrass prairies are so hard — or almost impossible — to re-create. The most diverse part of the prairie is belowground. Try to picture a teaspoon of soil, harboring over a billion organisms, which prairie soil does.

Diversify root systems

Restoration biologists and horticulturists are busy scratching their heads, trying to figure out how to replicate this in reconstructed plant habitats, built landscapes and gardens. As you can imagine, this area of study is in its infancy, and there is still much to learn and discover.

But as for plant root anatomy, there is consensus among experts. Plant roots come in all sizes and shapes, and they are critical for rainwater infiltration into the soil. That’s why rainwater runs over the surface of mowed lawns but moves down into the soil where there are taller plants.

BELOW THE SURFACE: Prairie roots come in many forms, from thick taproots to fine networks. Note the shallow roots of non-native turf grass at far left.

Turf roots are about 3 inches deep, compared to the roots of garden plants that may be 2 to 3 feet deep, depending on how deep the topsoil is. In construction areas, topsoil is shallow or gone altogether.

It takes years for topsoil to improve. It doesn’t improve much if all you grow is lawn, but if you introduce a diversity of plants, you will find that, slowly, organic matter will increase, compaction will decrease, plant roots will grow deeper, and rainwater will move into the topsoil quicker.

It may take a decade for topsoil to noticeably improve, so adding several inches of topsoil or tilling compost into the soil surface of new gardens will improve topsoil faster.

So next time you hear that native plants have deep roots, think again. After all, not all goldfish are gold.

Woodbury is a horticulturalist and the curator of the Whitmore Wildflower Garden at Shaw Nature Reserve in Gray Summit, Mo. He also is an adviser to the Missouri Prairie Foundation’s Grow Native! program.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like